When your friend gets tipsy and starts rambling about how tequila turns her into a savage party monster, and then your other friend vehemently calls bullshit, calmly put your hands up and say this: “Friends. Please. I got this.” And then explain to them what I’m about to explain to you.

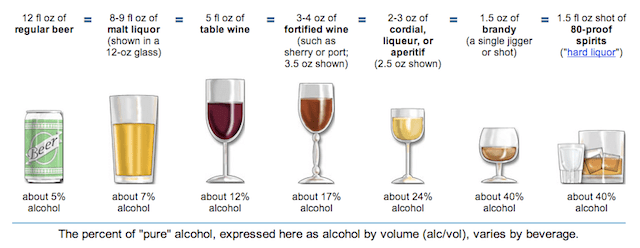

First off: alcohol is alcohol — which is to say that the alcohol in wine is the same as the alcohol in beer is the same as the alcohol in the unholy red-cup concoction at a dormroom game of King’s Cup. That alcohol is ethyl alcohol, aka ethanol, and it will get you drunk. The fact that liquor tends to contain higher concentrations of ethanol than wine, and wine higher concentrations than beer, means that the same volume of different alcoholic beverages will get you more/less drunk, ergo the “standard drink” rule, as defined by the National Institutes of Health:

In the United States, a “standard” drink is any drink that contains about 0.6 fluid ounces or 14 grams of “pure” alcohol. Although the drinks below are different sizes, each contains approximately the same amount of alcohol and counts as a single standard drink.

The standard drink model suggests that when it comes to behavioural effects, the only difference between a can of beer and a shot of whiskey is the mode of delivery. Ounce-for-ounce, an 80-proof shot of MaCallan’s is a much more efficient ethanol-delivery system than a can of Bud Light. If you down a few shots of the former really quickly, you’ll experience a rapid spike in your blood alcohol level, and, presumably, a rapid drop in your inhibition, sense of propriety, and so-forth. But any perceived difference between the drunk you feel from the liquor and the drunk you feel from beer has to do with the rate at which you consumed the ethanol, not the beverage via which you consumed it.

But what about hard alcohols that are comparable in ethanol concentration, and therefore equally efficient at getting you drunk? According to the Alcohol Is Alcohol argument, 80-proof tequila should have the same effect on you as 80-proof vodka, rum, gin or whiskey. Yet we all know someone who insists that tequila makes them wild, that whiskey makes them angry, or that gin makes them sad. Why is that?

One possible explanation: mixers. Lots of people shoot tequila straight, whereas rum is commonly taken in tandem with something else — cola, for example. If you’re combining gin with tonic, or vodka with something super-caffeinated like Red Bull, who’s to say the drunk you’re experiencing is due to the alcohol, and not because of what you’re drinking with it?

Another explanation: congeners. Congeners are byproducts of the fermentation and distillation process, and include chemicals like acetone, acetaldehyde, and esters — not to mention forms of alcohol other than ethanol. Different alcoholic beverages contain different types and quantities of congeners, so even though 80-proof vodka, rum and gin all contain the same amount of ethanol, their congener content can vary considerably. This variation contributes mainly to tan alcohol’s colours and flavours, but may or may not also have an effect on the “flavour” of drunkenness it imparts — the lacklustre (but still technically valid) justification being that different chemicals affect everyone differently, in ways we may not fully understand.* Take coffee, for example: we know it makes you have to poop, but we really aren’t clear on why that is.

All of the above being said, despite the fact that there are no scientific studies (to my knowledge) that examine the behavioural effects that different alcoholic beverages may or may not have, the most common explanation for the differential effects of booze is that it’s all in your head, and that your experience with a given alcohol is dictated largely by the social situations in which you choose to consume it:

“A lot of this is folk memories and cultural hangovers,” says pharmacologist Paul Clayton, former Senior Scientific Advisor to the UK government’s Committee on the Safety of Medicines, in an interview with The Guardian. He continues:

A lot of it depends on what mood you were in when you started drinking and the social contex. The idea that gin makes you unhappy probably comes from its nickname “mother’s ruin” – the idea that it makes women depressed, which is a cultural idea. But fundamentally, alcohol is alcohol whichever way you slice it.

The psychosocial explanation for alcohol’s differential behavioural outcomes closely resembles the results of studies on alcohol expectancy effects, which examine not only the way people behave when they have ingested alcohol, but how they behave when they think they have ingested alcohol. Consider for example that even when test subjects are given a standardised dose of ethanol, and attain the same blood alcohol level as other study participants, their reactions tend to vary dramatically. Some act utterly sloshed, while others barely bat an eye. According to a 2006 review paper on alcohol expectancy effects, there’s evidence that this variability may stem from differences among test subjects in the how they expect to be affected by the alcohol they’re consuming:

Studies of alcohol effects on motor and cognitive functioning have shown the individual differences in responses to alcohol are related to the specific types of effects that drinkers expect. In general, those who expect the least impairment are least impaired and those who expect the most impairment are most impaired under the drug. Moreover, this same relationship is observed in response to placebo.

In the end, our expectations can have tremendous sway over the perceived effects of an alcoholic beverage (or non-alcoholic, for that matter). In this light, the question of whether mixers or congeners affect our experiences with different alcohols seems almost inconsequential; if you whole-heartedly believe that a tequila shot is your one-way ticket to Bedlamtown, there’s probably not a whole lot that can be said to convince you — or your body — otherwise.

*Certain congeners are also thought to cause more unpleasant hangovers, though experiments with animal models have shown that fusel oil — a congener found in whiskey — may actually alleviate the after-effects of heavy drinking, contrary to common belief. Still… are the congeners in whisky different enough from those in tequila for the first drink to make you belligerent and the second to put you on the express train to fiestaville? Mehhhhhhh….

Images via Shutterstock

This io9 Flashback originally appeared in April, 2013.