On an forbidding shoreline at the bottom of the world, the prodigious ice sheets of West Antarctica dead-end in the Amundsen sea. For decades, scientists have been monitoring this interface of rock, ice and ocean in order to understand how quickly it will retreat as the planet warms up. A new study shows that three of the Amundsen sea’s frozen gateways are melting away faster than we realised, raising the spectre of an ice sheet collapse that could trigger a metre of global sea level rise.

Aerial view of Mount Murphy captured during a NASA Operation Ice Bridge flyover in 2012. Image: John Sonntag

Scientists have long viewed the Amundsen sea embayment as the Achilles heel of West Antarctica, with papers in the 1970s and ’80s describing it as “uniquely vulnerable”, “unstable” and the “weak underbelly” of the continent. The fear, then and now, was that warm ocean waters lapping against the foot of the glaciers could cause the ice to pop up off of its rocky floor, like ice cubes rising as a soft drink is poured into a glass. When ice detaches from its so-called “grounding line”, it kickstarts a chain reaction that can trigger a lot of melting.

“When water gets between ice and land, it moves quickly, bringing lots of heat in, and melting the ice above it more rapidly,” said Thomas Wagner, the director of NASA’s polar science program. “The Amundsen sea embayment is a place where we know this is happening.”

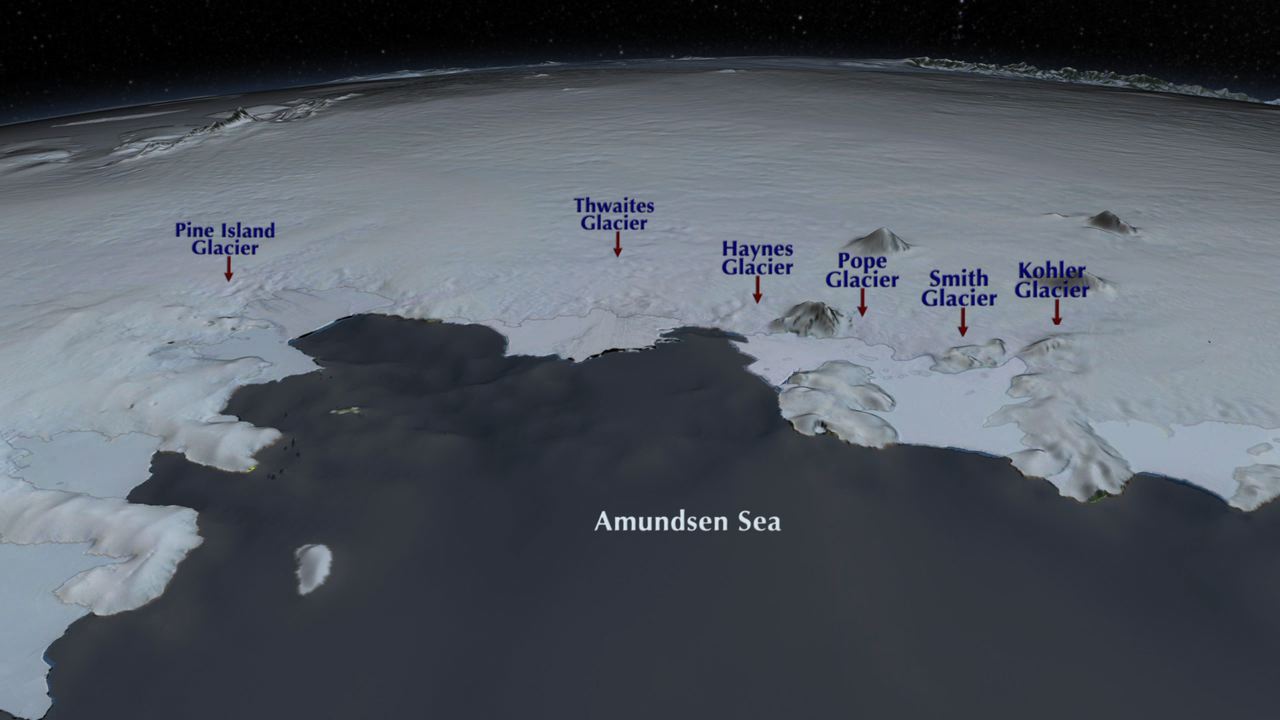

Bird’s eye view of the Amundsen sea embayment, where major glaciers of the West Antarctic ice sheet empty into the ocean. Pope, Smith, and Kohler glaciers were the focus of this study. Image: NASA/GSFC/SVS

Indeed, satellite and radar data show that two of West Antarctica’s largest glaciers, Pine Island and Thwaites, have seen their grounding line retreat many kilometres since 2000, causing fresh water to pour off the ice and into the ocean. This process is so effective that glaciologists recently declared the total collapse of the Amundsen sea embayment — whose glaciers contain enough water to raise global sea levels by 1.2m — to be “unstoppable.”

Here’s the rub: We still have no idea how quickly all of that ice will go, meaning we have no idea whether to prepare for a lot more sea level rise in 10 years, in a generation or at the end of the century. A new study, led by glaciologist Ala Khazendar of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, points to ice disappearing sooner rather than later.

For years, NASA has been conducting an airborne campaign called Operation Ice Bridge, flying across sections of our planet’s north and south polar ice sheets and using ground-penetrating radar to measure changes beneath the surface. When Khazendar examined Ice Bridge’s datasets for the Amundsen sea embayment, he realised that NASA flew almost exactly the same path in 2009 that it did in 2002. “This presented an excellent opportunity to look at how ice thickness changed,” he said.

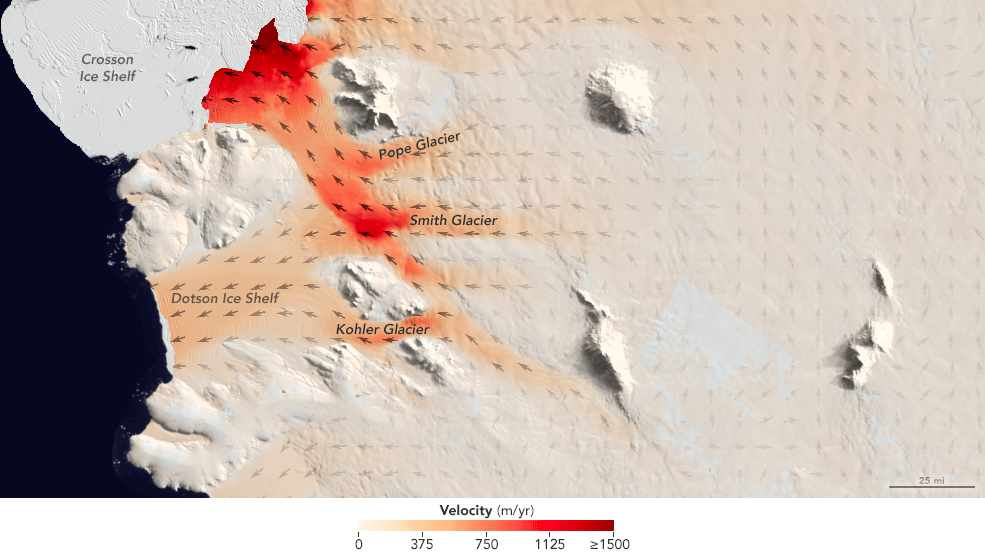

Flow speeds at Smith, Pope, and Kohler Glacier. Image: NASA

When Khazendar examined changes in the thickness of three glaciers — Smith, Pope and Kohler — he discovered significant thinning near the grounding lines. Smith glacier, in particular, stuck out like a sore thumb: In just seven years, this ice sheet shed 300 to 490m of ice from its underbelly. “What we have observed is rates [of melting] under Smith and other glaciers that are tens of meters per year out of balance,” Khazendar said. “This was really staggering.”

“We generally knew thinning was going on here,” Wagner said. “But this is an incredible study for combining all of the different data we have.”

None of the glaciers Khazendar looked at is particularly massive. But it’s reasonable to assume that the rates of ice loss measured in this study could be comparable to what’s happening at larger glaciers. In particular, the rapid wasting taking place at Smith glacier, which is grounded more than 2000m below sea level, suggests that other deep-rooted slabs of ice might be especially prone to collapse.

Most of all, the study highlights a desperate need for more direct measurements, in order to understand how fast, where and why Antarctica’s icy fortress is shrinking. “These glaciers are the gates and the gatekeepers for Antarctica,” Khazendar said. “They are changing very rapidly, and we need more data.”