Asteroid mining has gained steam in the popular psyche: who doesn’t love the idea of flying up to one of the giant rocks flying by and somehow harvesting it of its precious metals like platinum. But today at the 2017 meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of the Sciences, scientists considered whether we should pursue another, far more likely alternative: mining the seafloor.

Humans are always looking for sources of metals. We know very little about one source with enormous potential, the ocean. We love digging for stuff, selling it and polluting the environment with the byproducts, so why not dig beneath the seafloor with its untapped potential?

There are lots of reasons to start looking for alternatives to on-land mines. I assume you like technology, for example. Companies need metals for that, and lots of them. Modern cell phones have around sixty different metals, two-thirds of the periodic table, explained Thomas Graedel, professor emeritus of industrial ecology from Yale University.

That means we will continue to need mines, since the total amount of produced copper will begin decreasing some time from 2030 to 2050, depending on how our future plays out, as we mine copper mines to their capacity and as the population increases, according to a report in Science.

Image: Schmidt Ocean Institute

There are environmental concerns for on-land mining, too. The metals that companies actually use only make up a few per cent of the ore that miners pull from the ground. The waste goes into places like tailing ponds. Tailing ponds can have issues should the dams holding them back fail, potentially sending toxic sludge into the environment and even killing people, like in the 2010 disaster in Kolontar, Hungary.

So what about the seafloor? It’s an idea that’s been around for decades but continues to gain popularity. “Whether or not deep sea mining can make a difference, the perceived pressures on resources are already causing a gold rush mentality on the deep sea right now,” said Mark Hannington, geologist at the University of Ottawa in Canada and the GEOMAR-Helmholtz Center for Ocean Research in Germany.

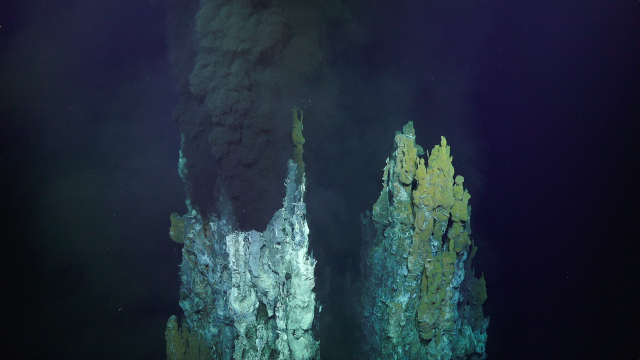

The deep sea contains several different sources of the metals we’re looking for. So-called manganese nodules cover parts of the seafloor, and makeup billions of metric tons worth of lumps containing manganese, nickel, cobalt, copper and other metals waiting for trawlers to scoop them up, Hannington said. Other parts of the crust are embedded with the precious metals, too, but Hannington thinks the first serious mines will pop up around volcanic geothermal vents. “They contain high-value commodities like copper, zinc, silver and gold,” he said. “They’re a primary target because those [locations] that are of interest are in exclusive economic zones,” areas where country have exclusive rights to the sea floor.

Manganese nodules. Image: Flickr user James St. John/Flickr

Countries like South Korea have already started building miners to scoop up ore, but seafloor mining is still loaded with uncertainty. Mining needs to cost less than a few hundred dollars per ton of metal in order to be worthwhile, said Hannington.

Scientists don’t know how much metal is embedded in the crust or if there are enormous underwater deposits similar to land deposits like the Kidd Creek mine in Canada. Scientists simply don’t know enough about the ocean to determine whether mining is worthwhile yet. “How could we come up with an informative resource assessment if our sample size,” the amount of area mapped to the most precise detail, “is only half a per cent of the total area of the ocean,” asked Hannington. “There’s no option except to keep exploring.”

Scientists know relatively little about deep sea mining’s environmental concerns. They do know that a four-kilometer-across on-land copper pit would equate to a 100km manganese nodule mining area, said Hannington. Scooping up all of those nodules could disturb the microbial life in the ocean floor sediment, as well as anything living on the nodules.

As for the vents, disturbing these ecosystems might require forfeiting other things, like the potential for discovering new chemicals with pharmaceutical applications in these strange conditions, explained Stace Beaulieu, Research Specialist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She said scientists, miners and policymakers must ask themselves the following question: “What economic impacts do you anticipate from lost or degraded ecosystem services” that come along with mining?

The talk ended without coming down on either side of whether we should mine the seafloor. A pair of scientists sitting behind me scoffed and whispered “no,” but that won’t stop countries or companies like Nautilus Minerals from prospecting. Nor will it stop the International Seabed Authority, an independent organisation in which 167 countries (but not the United States) are members, from passing regulations and making recommendations on the practice.

Regardless, it’s far more likely we’ll see serious deep sea mining than the much-hyped asteroid mining, thought Graedel. “NASA is pretty good at getting things up into space, and I believe they can capture an asteroid,” he said. “But NASA doesn’t know anything about mining… I won’t say that we’ll never see [asteroid mining], but don’t think anyone in the room will live to see it.”