To help celebrate the school’s 200-year anniversary, students at the University of Michigan have decided to build a time capsule. Boring, right? Not exactly. Instead of burying it, which would inevitably lead to its contents rotting away, the students want to blast it into space where it will orbit the earth for 100 years, potentially giving it a better chance at surviving.

Photo courtesy University of Michigan

The process of creating a time capsule usually involves building what is essentially a miniature vault designed to protect what’s inside — be it photos, memorabilia, newspapers or whatever — from the elements and anything else decades of neglect can throw at it. More often than not, it fails, resulting in a disappointing reveal when it’s eventually opened. But in space there’s no moisture, oxygen or microscopic creatures that can destroy what you’re trying to preserve.

Photo courtesy University of Michigan

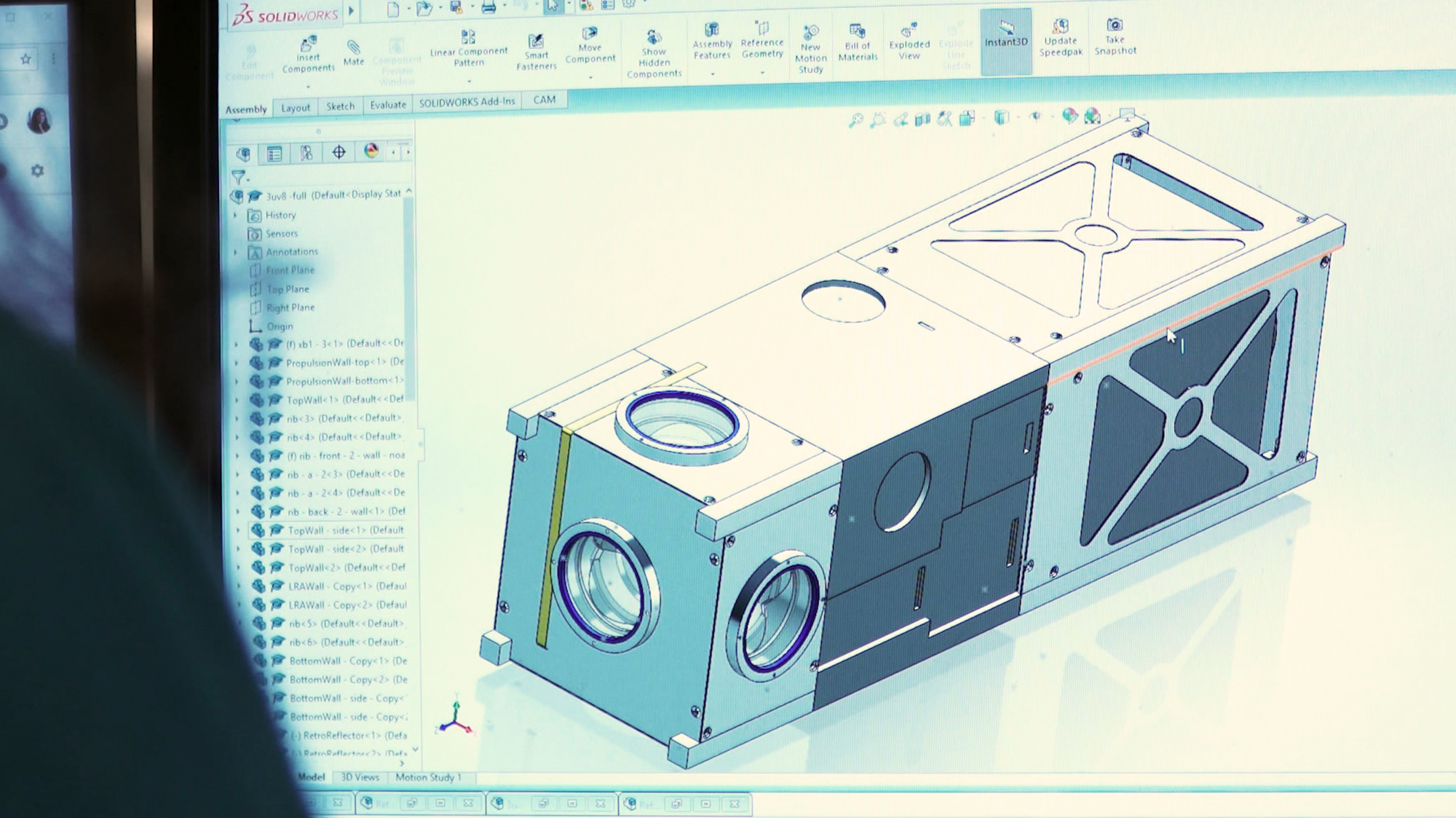

Instead of a vault, the University of Michigan students are designing and building a “cubesat” — a tiny satellite made up of 10cm cubes — that will contain almost 1000 interviews from students at the school, all microscopically etched onto silicon chips. The tiny time capsule will also feature the school’s mission statement encoded onto synthetic DNA, so that in 100 years future students can study how well it holds up after a century in space.

There won’t be any photographs or newspaper clippings stuffed into the cubesat time capsule, however, as the students need to maximise the limited space they have available to incorporate a propulsion system — the first to be incorporated into a tiny satellite like this. Earth’s gravity eventually pulls everything orbiting our planet back down, and to keep this time capsule up there for 100 years, it needs its own propulsion system to counteract the pull of gravity.

Photo courtesy University of Michigan

But there’s yet another challenge to designing a satellite that will eventually be retrieved after 100 years in orbit: It won’t be able to carry enough power to communicate with the Earth the entire time. Eventually it will go silent, so the students have integrated external reflectors into its design so that when 100 years is up, students of the future can use a ground-based laser system to scan the skies until they can visually detect it. At that point they will also be able to track its orbit, and calculate where it will eventually crash to earth when its orbit decays.

The experiment is certainly a creative way to ensure that the time capsule’s contents survive the century-long trip. But after 60 years of sending rockets, satellites and other spacecraft into orbit, it’s also getting really crowded and cluttered around our planet. So maybe the last thing we need is everyone blasting time capsule satellites up there that do nothing more than just hang around, in the way, for 100 years.