While the flightless dodo has long since died out — because humans ate the crap out of them — its memory lives on in our imagination. So much about the quirky birds — which were endemic only to the island of Mauritius — remains a mystery, but new research has finally provided some insights into the dodo’s reproductive habits and life cycle.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

A study published today in Scientific Reports analysed the structure of 22 bones from 22 different dodos (Raphus cucullatus) collected from various places on Mauritius. Some of the bones were from juvenile dodos, which curiously contained a lot of tissue known as fibrolamellar bone. Fibrolamellar bone is typically found in rapidly-growing dinosaurs, birds and mammals, so the researchers suggest dodos grew very quickly until they reached their sexual maturity.

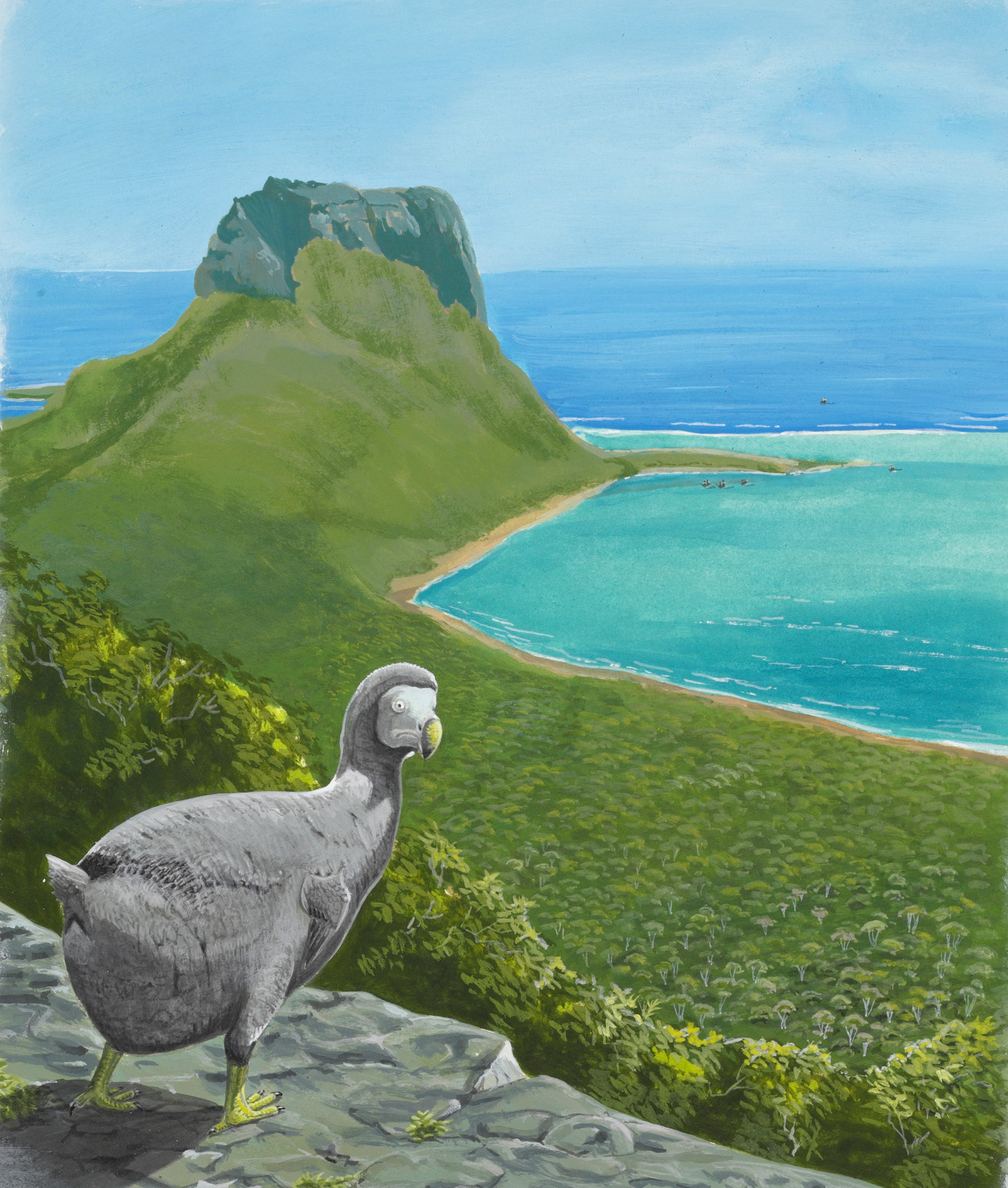

Image Courtesy of Julian Pender Hume

Some bones contained unusual cavities, which the team believes is linked to the dodo’s moulting, or natural shedding of its feathers. The researchers say that this, along with other observations from dodo bones, could actually help explain the timing of dodos’ reproductive cycle.

“We propose that the dodo bred around August and that the rapid growth of the chicks enabled them to reach a robust size before the austral summer or cyclone season,” the researchers wrote. “Histological evidence [based on microscopic analysis of tissue] of molting suggests that after summer had passed, moult began in the adults that had just bred; the timing of moult derived from bone histology is also corroborated by historical descriptions of the dodo by mariners.”

Unfortunately, there’s still so much about dodos we don’t know, because they have been gone for nearly 300 years. But if knowledge is truly power, then every study about these birds is a bit of justice served. RIP, good birbs.