Like hundreds of thousands of other people around the world, Tananarive Due saw Get Out earlier this year. Blown away by the hit horror movie, the author and educator decided to design a semester-long special course about how horror and anti-black racism have intertwined in the cinema.

Image: Sharlene Artsy for Universal Pictures

Best known for books such as My Soul to Keep and The Living Blood, Tananarive Due has been creating speculative fiction centred on the Afro-diasporan experience for decades. She’s also a filmmaker and professor, having taught a course on Afrofuturism at UCLA for the past several years. When I talked to her on the phone last week, Due described herself as a lifelong horror fan and said that seeing Get Out got her thinking about how she could teach the history of horror genre work made about or by black people. The result of that thinking is “The Sunken Place: Racism, Survival and Black Horror Aesthetic“, a class that starts on September 28 at UCLA. In the edited and condensed conversation that follows, Due talks about early Hollywood horror, how Get Out has already changed the project development pipeline, and her own journey as a writer.

Let’s start by you talking about where you got the idea for the course. Was it just from seeing Get Out?

Tananarive Due: Well, number one, I’m a horror head. That is just a constant in my life. But the idea for the course, specifically, came because Jordan Peele dropped Get Out when I was teaching my Afrofuturism course last spring at UCLA. And it was one of those things where the timing wasn’t quite right and I thought, “Oh, I wish I used that in the course…”

I’ve taught the Afrofuturism course, I think, about four times. And I thought, “You know… horror, to me, is a subset of Afrofuturism, in that fantasy is a subset of Afrofuturism.” So, I decided, instead of doing the broader course, why not just break open black horror? Because Get Out is not the first black-made horror film, but it’s definitely the most successful. And I think it definitely has the ability to be culture-changing, let’s say.

I also do some screenwriting, I’m always trying to adapt my own work, and you know, often that’s horror. You have to almost find a language to help the executives understand your horror as opposed to what they see as horror. Like, I’m not pitching that story about a group of white teenagers terrorised by a stalker in the woods, right? My ideas weren’t fitting the models of what they thought horror looked like. And the examples of previously made films just weren’t strong enough.

And what were the examples?

Due: One that was persistent was Beloved. That was the only reference point a lot of these executives had for what black horror would look like.

And that’s probably only because of the adaptation from years ago, and not the Toni Morrison novel itself.

Due: Jonathan Demme did the film and — you know, of course I have the greatest admiration for Toni Morrison and that’s a Nobel-Prize winning novel — but the film did not do that great at the box office. So, it was always an awkward comparison in a pitch scenario. Just this year, just recently, we were talking to some network execs about a pilot we were developing… and they were like, “Oh, like in Get Out. You can do — blahbiddyblahbiddyblah…” And it’s not that it’s anything similar to Get Out, it’s just that was now the new framework. That’s what black horror looks like: Get Out. They can now have a reference point and you can continue with the conversation. Because before, you could barely even get that conversation started.

This amazing renaissance we’re seeing right now of black speculative fiction and literature is really starting to bleed over — no pun intended — into film and television. I mean, I can list so many writers who have active TV development right now. Nnendi Okorafor has Who Fears Death at HBO. N.K. Jemisin’s The Fifth Season at TNT. Victor LaValle with The Ballad of Black Tom at AMC. Clearly this is the moment, right?

Between Get Out and Black Panther and A Wrinkle in Time coming out, with Ava [DuVernay] directing a multiracial cast… there’s just never been a time like this. For artists and consumers of black, speculative art.

You asked a very specific question about, “Why horror?” Look: I love horror. But it never dawned on me that I could have a black horror course before Get Out. When a movie like that comes along, you now have a reference point to talk about everything that has come before. [“The Sunken Place”] is going to be a black horror overview course that will be very cinema-based. It will look at cinema going back to the ’30s. Both black-made movies and films that have blacks featured, which were very, very different movies then and are still usually very different movies now.

I mean, D.W. Griffith’s original Birth of a Nation is essentially a horror movie. It’s white supremacist propaganda that depicts black people as monsters…

Due: I’ve been thinking about including Birth of a Nation as a horror movie. Because, in a lot of ways, it was just a really on-the-nose way of doing the same thing subsequent movies would do later with the buffoonery and the idea of black menace.

There was a scene in a Mantan Moreland movie called Lucky Ghost from the ’40s where they put a plate of food in front of him. And the way he’s eating the chicken reminded me so much of Birth of a Nation and the scene in the legislature.

And I was just like, “OK, these portrayals are clearly connected…” While I’m doing a cinema-based overview course, I don’t want to leave out the writers. So, to try and keep costs down, I think I’ll have an emphasis on short fiction [as far as literature is concerned].

So far, what readings are you thinking about including?

Due: I’m still narrowing my list, but it will include writers like Nishi Shaw, Nalo Hopkinson and Kai Ashante Wilson. Those are the ones I’ll name for now. There’s certainly more I could include if I wanted to have five or six books in addition to short stories. I’m trying to think of how to get Victor LaValle in this course, too, and even those Dark Dreams anthologies that Brandon Massey edited back in the day. But they’re not that easy to get a hold of, now.

I could probably get [Massey’s] permission to photocopy some of those to share with the students. But the fact that a book like that is out of print becomes a problem, when you’re trying to teach a course and want students to have access.

I know you worked as a journalist before writing fiction. Was it hard to make the leap?

Due: I’m not going to lie: It was fun when I quit my job. I was a reporter for The Miami Herald for 15 years. And God bless everybody there, journalists are beautiful people, I learned a lot, but… woo. That day I left, that was such a liberation. I just knew, in my heart, I was supposed to be writing fiction. Because, really, I needed to explore that part of me that was a fiction writer. We often talk about all the people who might not even think about [doing fiction or genre work] if there weren’t other examples of writers doing it… I really had to struggle to give myself permission to write horror.

Your parents were in the Civil Rights Movement, which is a powerful backdrop for thinking about horror and the black existence in the United States of America. Everything from the Middle Passage onward has been fraught with horror. So, it’s interesting to say you had to give yourself permission to write horror, because it’s never been that far.

Due: You are absolutely right in terms of the themes. The emotions. Yes. We have been right in there in that horror experience. But I was a developing writer looking out at the publishing industry and, really, it took Stephen King to create the horror subgenre. He created the horror section in bookstores. There are a lot of other great horror writers but I really feel like Stephen King anchored that whole thing. But I was not seeing myself on those shelves, let’s just say, in any of that work. It was not reflecting my experience. That’s one part.

Here’s the other part: My father is a civil rights lawyer. He and my late mother, Patricia Stephens, were very well-respected in the community. I felt that it was veering off the path enough to not to go to law school, especially when both my sisters went. I felt blessed that my parents were deeply encouraging of me wanting to be an artist, but I didn’t want to embarrass them. I can’t be publishing anything that will bring them shame. This is all the voices in my head. It took a long time, especially without role models. I had read Mama Day by Gloria Naylor but I had not even discovered Octavia Butler’s work. I had a conversation with Anne Rice. She didn’t know I was a writer so she didn’t know she was giving me advice. She helped me get past my mental block about not being respected as a writer, by raising the idea that her book was taught in colleges. In the end, I was mostly just stepping out on faith.

Getting back into the coursework, how far back in cinematic history are you planning to go?

Due: I’m going back very far. I don’t know if I’ll make students watch all of Birth of a Nation. But we’ll definitely be touching on that as a jumping-off point for how Hollywood has a special responsibility for the proliferation of white supremacist imagery. It really does. And I think that really calls for a responsibility to come fix it. We can start with White Zombie, which is not a film about black people, but it’s a film about black people and black magic.

There is a fantastic book called Horror Noir: Blacks in American Horror Films from the 1890s to Present by Dr Robin R. Means Coleman, who teaches at the University of Michigan. This book is gold. I thought I was a horror head, but she goes so deep into it, just speaking my language. Everything she says I’m just like, “Yes… that’s exactly what I always thought.” It’s so nice to find a scholarly book that addresses what your friends have been talking about for years and just breaks it down. That is one of the underpinnings of the course, to bring the experience of being viewer and subject into an academic framework.

Starting with Birth of a Nation, I’m planning to look at how fear of black otherness and black power were there from the start. Ingagi really helps introduce this fear and that was 1930. It has this notion of magic and a fascination with voodoo that became so Hollywood-ised. That fascination has continued, and it’s not just in white-made films to be perfectly frank. But there’s a difference, usually, in the rendering of it. Early Hollywood very much used this sort of fear-mongering. Either we were beast-like and scary and we had scary, magical ways that might harm them. Or we were the comic relief and less brave, more cowardly.

Those tropes still pop up, maybe not as prevalently as they once did.

Due: Oh yes. I had never watched a Mantan Moreland film before preparing for this course. I mentioned him in Lucky Ghost, but I want to include King of the Zombies, where it’s clear that he’s almost like a co-lead. The opening shot is two white actors and he’s in the back — the servant. But he’s almost centre framed. So he’s one of the big draws for this movie, and he is hysterical. The man was a talent. There’s no questioning it. But the stereotype was so toxic.

It’s such a shame. You can see he was such a talented man, but he was a part of a system that was using him to aid and comfort white supremacy. This notion of cowardliness and all the child-like presentation, which really marked a lot of portrayals in those early Hollywood films. So we’re going back to the beginning, and we’re going to go through the Blaxploitation Era with Blacula, of course.

You know, that really holds up. I like Blacula. I am really thrilled with how well some of these films hold up. I was really thrilled with Blacula. I finally saw Ganja and Hess, which, for years, was very difficult to find but is now streaming on Amazon. It is amazing. Duane Jones from Night of the Living Dead also stars in Ganja and Hess in a very different, really powerful role.

I really liked rewatching Rusty Cundieff’s Tales from the Hood from the ’90s. You go back and watch that now and it really resonates. Black-made horror tends to fall into categories of morality tale, which is what we have with Def By Temptation and some older ones in that vein. Or there’s power and magic that again returns to voodoo hoodoo in slightly different ways, in the form of retribution horror. Tales from the Hood is definitely retribution horror.

Some [other films] were just, “Hey, we’re here.” Nothing remarkable about the race of the characters, except they happen to be black. There was one from the Blaxploitation era called Abby. It was almost called Blacksorcist. They came this close to calling it Blacksorcist. It has some African themes in there. Often you’ll see these filmmakers bringing in African themes to enable the explanation for the magic. It’s got like a sex killing spree but it’s mainly just trying to capitalise off the popularity of The Exorcist. That’s all that really is about. I mean, they just sprinkle some African on it. But it’s really just more, “Let’s get some of that money…”

It’s really interesting to watch the difference between how black actors were used in horror movies made by white filmmakers, as opposed to what they do under their own power and direction. And that’s great; don’t get me wrong. For instance, the movie Son of Ingagi was made by a black filmmaker back in 1941. They called it Son of Ingagi I think to kind of counter the Ingagi movie, which was so exploitative and misappropriated voodoo. They kind of nod and pay homage to having a beast-creature in Son of Ingagi. But, more importantly, it was just showing black folks in daily life. This is a wedding, this is a well-kept home, these are well-spoken people, here’s a lawyer. The lawyer is black, the police chief is black, everyone is black. And when you think about what images that we got to see of ourselves back in those days, even a relatively schlocky horror movie like Son of Ingagi becomes this cultural timepiece. It really makes you think, “Wow… it would have been refreshing to see black people acting with courage. And it would have been refreshing to see black people not in a subservient position to whites in a movie.” In fact, there are no whites in that movie.

It’s striking that it came out only a year after the first one.

Due: Yeah. We’ve been doing this kind of call-and-response since the beginning. Trying to define who we are and what we’re like within their strictures. And of course there’s a vast difference in production quality.

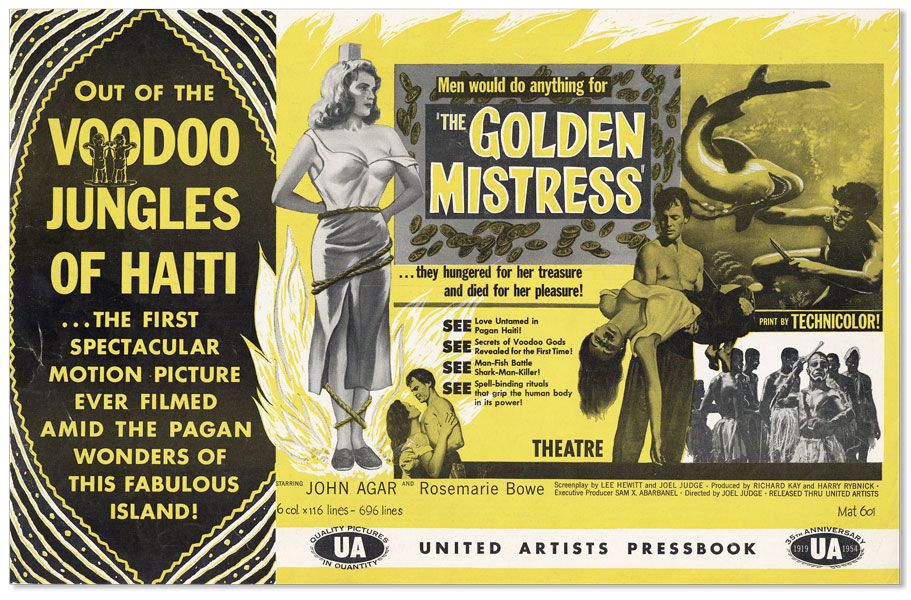

It’s funny, you talking about Son of Ingagi brought back this personal memory. My grandfather was a Haitian folkloric choreographer of some note and acted in a movie called The Golden Mistress. I’ve only seen it once. But he plays one of the village people, one of the guys who can speak English. There’s treasure and they go to the island of Haiti, and he’s the guy the white ship captain can talk to.

Image: United Artists

But he also plays a houngan [vodun priest] and wears a full face mask so you can’t tell it’s the same actor. And he wears, I think, a grass skirt and does a folkloric dance. On one hand, I’m watching this like, “Wow, grandpa was kind of like a freakin’ movie star?” On the other hand, it’s like, “Goddamn, they got him being a scary Other…” It speaks to your point with Son of Ingagi: You get to see like a tiny little bit of authentic representation in the middle of an embarrassing film.

Due: Yeah, it’s like this little island of black agency. Or their idea of black authenticity. But it’s a horror movie and there’s some bad costumes in it and clearly, they had no budget.

What are the works that you’ll use to show how portrayals changed?

Due: I am going to show “The Space Traders” from the old Cosmic Slop HBO sci-fi anthology, directed by Reggie Hudlin. Technically, that’s one that veers into science fiction but the story is about a horrific choice.

I kind of want to open with “The Comet” by W.E.B. DuBois. It’s an apocalyptic short story that I usually teach as science fiction, but it does kind of have a feeling of horror. He almost lovingly goes over the details of the bodies as they’re splayed everywhere. He was writing horror from the heart. And, of course, what he’s trying to counteract with that story is a different horror. This is the era of lynching and this is where the humanity of blacks is being questioned. When you write a story where everyone is dead except a black man and a white woman, they just have to become two people trying to survive for one little moment in time… that’s a horror story. These are two very different artists in two very different times but DuBois’ story is a great companion, in a way, to what Jordan Peele was doing with the black man and white woman in his movie.

They’re tapping into this primal fear that America has always had.

Due: Yeah, and they’re trying to hold up a mirror for us to see what we’re doing with our society. So, there were moments in the DuBois story where he’s nervous about where he goes and how he’s seen from the outside. It’s similar to the opening of Get Out, being lost in a strange, white neighbourhood. That’s so real. Horror is a great way to address this awful, festering wound in the American psyche, the slavery and genocide that was present during our nation’s birth. We has a nation have not been able to process it in a healthy way, or anything close to a healthy way.

And you’re seeing the consequences of that in the present, almost hourly.

Due: I knew it would get bad. But some things have happened much more quickly than I anticipated. I didn’t expect to see Nazis marching in the street and the president going like, “Eh…” I would have been really surprised if someone had come back in a time machine and told me that would be the case. It’s like, “You can’t be serious — you mean a white woman got run over? Not a black woman, a white woman? Got mowed over by a car?” And he’s like, “Eh…” Holy cow. That is worse than I thought, even. So, horror is really such a perfect way to express social evil through the energies and emotions of fictional characters.

I want to touch on George Romero for a moment, because we just lost him. I’ve been a big fan, obviously and, after he died, there was this debate on Twitter on whether he was intentionally trying to implant social messages in Night of the Living Dead. The famous story is that it was pretty much colorblind casting and Duane Jones just had the best audition and that’s the way it is. And people would just sort of close the book on that, almost angrily, like offended at that thought they might try to say something. I’m going to say this: It’s 1968. You have a black man in an alpha position in a story where he has hit a white woman and he’s killing a bunch of white folks. At the end, he’s shot down by a bunch of rednecks. Over the end credits, there are images of him being thrown on a woodpile by a group of rednecks. That imagery, whether it was conscious or unconscious, you can’t deny the power of it. As Dr Coleman points out in her book, black audiences saw the power of those images. Those kinds of images had not been addressed in a film at that time. The real horror is not zombies, the real horror is the social upheaval of the times. Romero went back to black male protagonists again and again. Hello, was that accidental?

I might have one intention with what I write but once you read it, what it actually means is what it means to you. Art is in the eye of the beholder and I know what I’m looking at when I watch Night of the Living Dead. I know how electrifying and unusual that is. So don’t try to tell me what was intentional or whatever. Unconsciously, he was doing something and he brought it to consciousness.

Are there things that persist, that still bother you, with black representations in speculative fiction?

Due: Oh my God, yes. It still annoys me when one of the rare actors of colour is coloured in paint, for example. Really? There’s the films that leave you out, and sometimes that’s better, frankly. Many times I have turned to my husband in a movie theatre and said, “Why don’t they just leave us out of this movie?” Because now I’m annoyed; before, I was having a good time. Especially when black characters are often not as three-dimensional as the white characters. If you have a lone person of colour in a big, white cast, they’re likely to be solitary. No friends or family to speak of. With a man, often no romance or a love interest.

That’s something that has been really persistent and really irritating is the desexualisation of black men but the open readiness and availability of black women for white men. That’s something that still persists to a degree. You do see strides, like This Is Us does do a really good job of blending its characters of colour into a big ensemble series. That’s because they have a diverse writing room. You know? And you can tell when a show has a diverse writing room and when they don’t. Colour has impact on us. You can’t just paint a character black or brown. Even if you just get to the point of treating them like everyone else, which is better than it’s been, there’s more to it. Where’s the richness of that experience?