Illustration: Chelsea Beck/GMG

As privacy barriers have gradually been eroded online, it’s become harder and harder to keep control over what you’re revealing to the websites you visit when you open up a web browser. For many users now, revealing who you are is just an inevitable consequence of being on the web and using apps, but if you want to tighten the reins on where your data’s going, you do have some options.

Privacy tools

Starting with data reported to sites by your browser, a plugin or extension is probably your best bet for stopping data from leaking out. Try NoScript Security Suite for Firefox or ScriptSafe for Chrome, which prevent active items on websites from running when you don’t want them too. Other good options include the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Privacy Badger, which blocks third-party tracking cookies while allowing useful, like those that record ones to continue operating, and Disconnect, which offers free add-ons that work in a similar way.

Image: Disconnect

We also like Ghostery, a privacy extension available for Chrome, Firefox, Opera, and Microsoft Edge. Like Privacy Badger and Disconnect, it stops cross-site, third-party trackers from running, and you can actually see a list of trackers on each site and choose to block or allow them as needed.

Built-in browser options

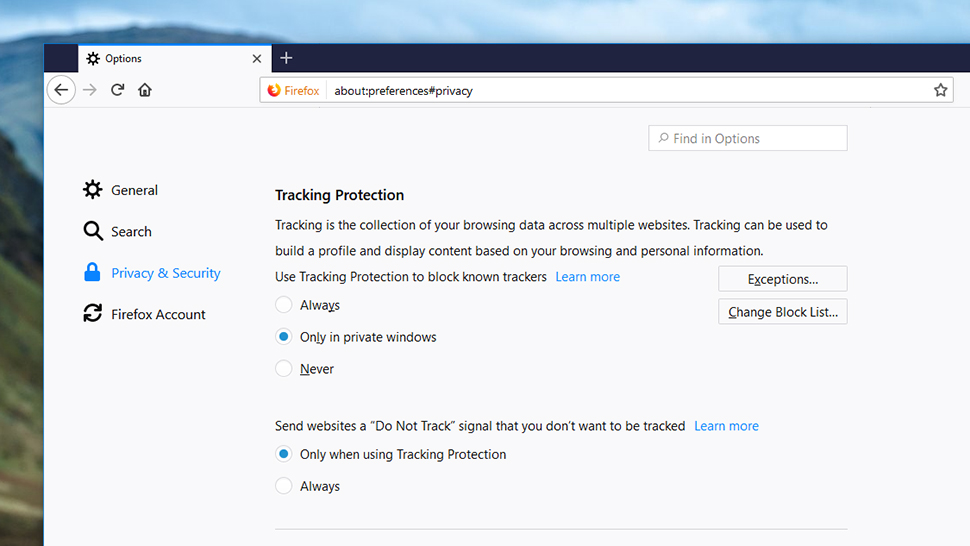

For more cookie settings beyond the extensions we’ve mentioned, head into your browser’s settings page. One of the settings will refer to Do Not Track, an agreed-upon protocol that automatically asks sites to not run any scripts designed to track your behaviour. It sounds like a perfect solution in theory, but there’s no legal obligation for websites to honour the request, and many will just ignore it. You can see some of the networks that respect a Do Not Track request, including Pinterest and Twitter, here.

Image: Screenshot

Opening up an incognito or private window can help. In these cases cookies are only kept for the current browsing session, so as soon as you close down the incognito window, they get erased from your system. From the perspective of the browser, it’s as if you were never online at all.

On the other hand, incognito mode doesn’t stop websites and ISPs from knowing you’re online. You’re still broadcasting your IP address, for example. And, of course, if you log into Facebook (or anywhere else) all the usual rules about tracking and data collection still apply. It’s best to think about incognito mode as hiding your browsing activity on your local device rather than adding any extra anonymity to your online travels.

Dial back tracking on services

Finally, there are the data-privacy options inside the services you use, which are worth reviewing. By visiting your ad preferences page on Facebook, you can limit the ways in which Facebook can target you, both on and off the social network.

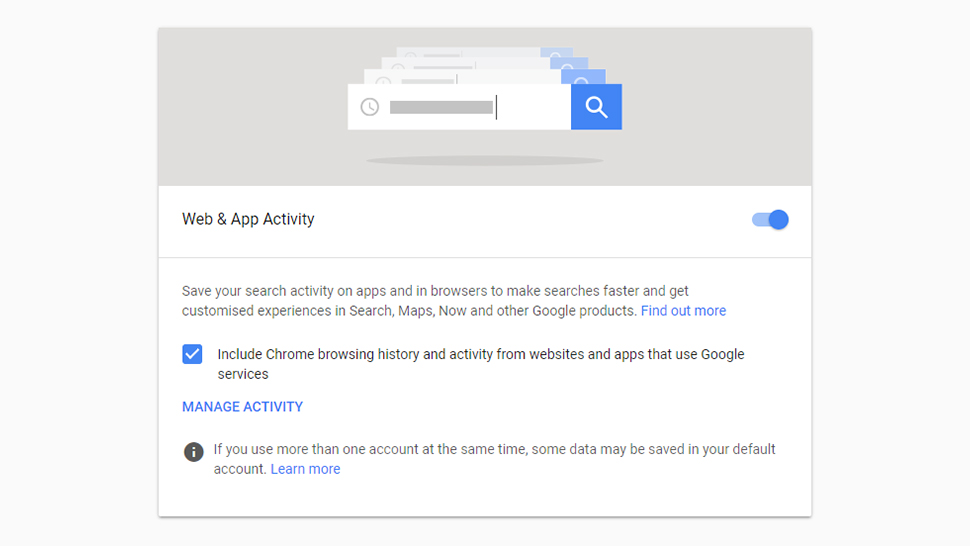

Image: Screenshot

Google offers a similar account page where you can do everything from opting-out of seeing personalised ads to deleting all of the searches you’ve ever made through Google.

Using as few apps as possible and registering for as few websites as possible obviously reduces the exposure of your personal information. But even if you’re aware of and activate all of these options, staying anonymous on the web is becoming an ever-more challenging task.

Setting up a VPN or DNS service

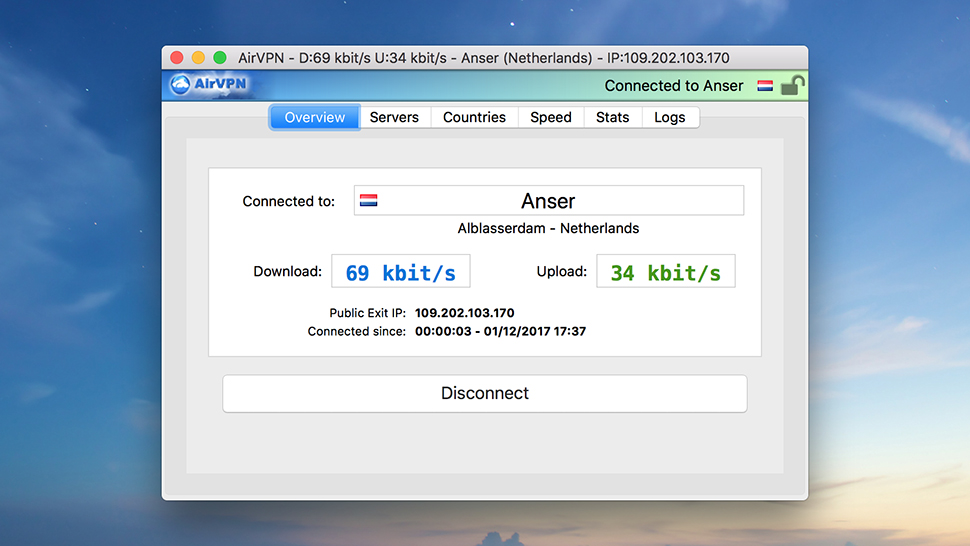

Installing a VPN (Virtual Private Network) will cloak certain bits of identifiable information, such as your current physical location. You should only install a VPN once you’re completely sure about what it does and doesn’t protect you against — it’s more of a security measure against hackers and eavesdroppers than a cloaking device.

Sign up with a VPN provider (you really need to opt for a paid VPN to be sure it’s reliable), and you’re essentially transferring your trust from your ISP to the VPN company, which can see all the sites you visit and everything you’re doing. Many firms promise to not log this data – but again, it’s a matter of trust.

Image: Screenshot

The websites you visit will see the IP address of the VPN server rather than your actual location, but they will still be able to leave cookies on your machine, track you across multiple sites, and know who you are if you log in anywhere. VPNs can be a useful extra step in being less trackable, but don’t rely on them completely to block your personal data leaking out onto the web.

Alongside VPNs are alternative DNS (Domain Name System) providers, like the recently launched Quad9 service. You need a DNS service to direct you to the right place on the web when you type in a URL. By default, your browser will use the one supplied by your ISP, which means it will follow whatever logging and tracking policies your ISP wants.

As with switching VPNs, switching DNS providers isn’t foolproof — you’re just putting your faith in a different company instead of your ISP — but it’s another way of extricating yourself from some of the tracking that’s happening. Quad9 is run by IBM Security and promises not to collect, store, or sell any information related to your browsing habits.

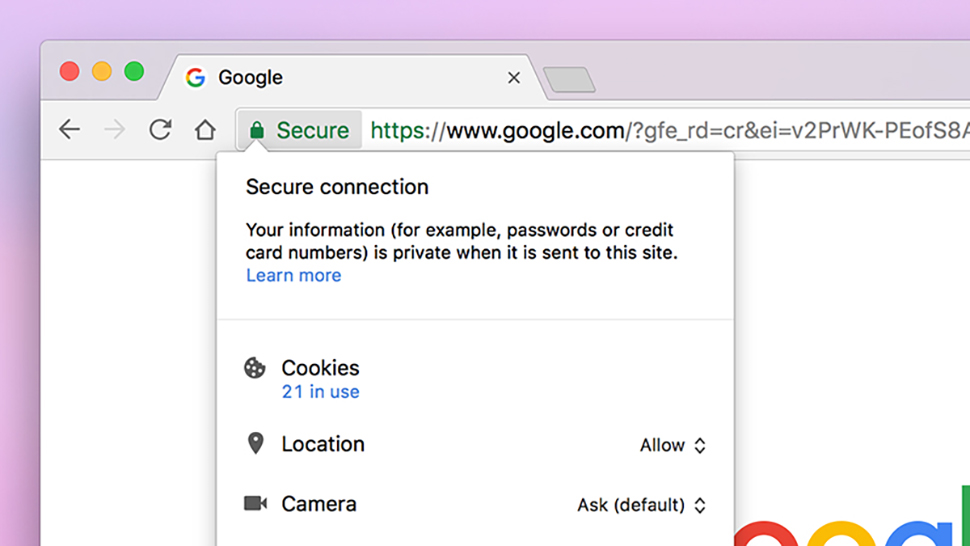

Finally, we’ll quickly mention HTTPs — the secure version of HTTP that encrypts data between you and a website like Facebook or Amazon. Its main benefit is keeping your data safe and hidden between point A and point B, but in terms of tracking, it stops ISPs from collecting quite as much data: They can see that you’re on Amazon, for example, but not what products you’re looking for.

Image: Screenshot

Many sites now use HTTPS by default, particularly those where you’re going to be entering sensitive information like credit card numbers. The HTTPS everywhere extension from the EFF will force your desktop or mobile browser to always use the HTTPS version of a site, if the website has one available.

Trying to completely block information companies gather on you on the web is very difficult to do, short of quitting all your personalised services and being incredibly careful about how you go online, but the situation isn’t quite hopeless yet. Follow all of the above, and you’ll be off to a good start.

This story was produced with support from the Mozilla Foundation as part of its mission to educate individuals about their security and privacy on the internet.