For the vast majority of living things, there’s nothing particularly sexy about sex. It’s mostly just an exhausting and dangerous hassle (just ask the insects who get their body parts stabbed or bitten off while mating).

Given that, it perhaps shouldn’t come as a surprise that at least one species of fungi has opted out of sex altogether, according to a new study published in Genetics. As it turns out, the species might have done so because it became perfectly compatible with something else: our danky-arse feet.

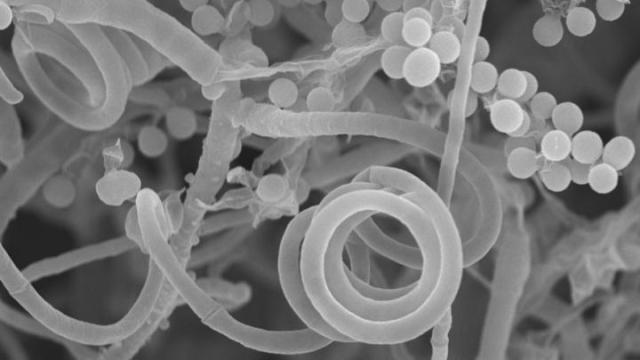

Researchers conducted a global survey of Trichophyton rubrum, the most common source of skin fungal infections in people. It’s the cootie behind toe jam and athlete’s foot. They collected more than 100 samples of the fungus from people in seven countries, including the U.S., Germany, and Vietnam, and analysed their genetic structure.

All but one sample belonged to a single mating type seen among fungal species that colonize the skin. And as hard as they tried, they couldn’t get these fungi to mate with a population of T. rubrum that belonged to the other type in a petri dish. Later genetic analysis found that any two random samples were about 99.97 per cent genetically identical to one another.

That indicates, the researchers wrote, that “T. rubrum is highly clonal and may be primarily asexual or at least infrequently sexually reproducing.”

Many species of fungus can reproduce both asexually and sexually, but the researchers believe that T. rubrum only became exclusively celibate only a short time ago, evolutionarily speaking. Their “remarkable” similarity across different populations of people suggests the species became genetically stagnant only once it made humans its exclusive source of nourishment. In other words, why fix what isn’t broken? Other fungi that do sexually reproduce tend to do so while hanging out in the dirt.

But this change likely didn’t happen too long ago, since the species’ genome is about as big as other related fungi and still retains the genes needed to sexually reproduce. If that weren’t the case, the researchers say, T. rubrum would be genetically slimmer and more much dependent on its human host to stay alive. Other research, meanwhile, has shown that, very rarely, T. rubrum does seem to produce spores indicative of just having mated.

Asexuality, though easier than being sexy, does come with drawbacks. Most importantly, it’s harder for these species to adapt to a changing environment. And sweeping changes that are cataclysmic – like, say, a powerful new antifungal drug – may even threaten the survival of the species. At the same time, asexual pests do have plenty of ways to evade our chemical weapons, as we’re brutally finding out now with the rise of bacterial superbugs. And there’s evidence that T. rubrum is also becoming increasingly resistant to common antifungals.

So while T. rubrum‘s virginity may someday prove to be its downfall, it won’t be anytime soon, according to senior study author Joseph Heitman, a professor and chair of the molecular genetics and microbiology department at Duke University’s School of Medicine.

“It is commonly thought that if an organism becomes asexual, it is doomed to extinction,” Heitman said in a statement. “While that may be true, the time frame we are talking about here is probably hundreds of thousands to millions of years.”

[Genetics]