Last week was full of startling, scary news about how carelessly Facebook treated user data and how Cambridge Analytica, a political consultancy previously led in part by Steve Bannon, abused access to that data, possibly for Trump’s presidential campaign. The news was all but obvious to those who follow the company closely, yet the implications of it were unnerving. As they realised where their data went, people on Facebook felt betrayed.

Photo: Adam Clark Estes

We should. Now, more than ever before, it’s clear that any of us with a Facebook profile has surrendered an unknowable quantity of information about our lives, our interests, our locations, our aspirations — and about our friends, our friends’ interests, our friends’ locations and our friends’ aspirations. That second layer of enigmatic data sharing is part of what makes this Cambridge Analytica scandal especially scary.

For years, granting Facebook app developers access to your info also gave them access to your friends, who never intentionally gave anyone permission. It’s absolutely frightening to comprehend what else you’ve given up.

This latest Facebook privacy scandal feels familiar and outrageous at the same time. It feels normal, because Facebook has been violating its users’ privacy for years. You might even say that people willingly gave up their privacy rights in exchange for this free service that made it easier to keep in touch with friends and family, privacy be damned.

That’s probably what Zuckerberg would like you to believe. Most people don’t pay much attention to the terms and conditions that explain the actual arrangement when you connect your Facebook profile to another app or website. They just click “allow” because that gets you to the part of the internet they want to use. Then, the targeted ads start flowing in, and before long, you forget you’re being tracked.

A group of Android users were recently reminded of this shifty exchange. They had, at some point, granted the Facebook app the right to collect all of their phone calls and messages. (According to Facebook, reading texts would make it easier to find confirmation codes.) But some were surprised this week, when developer Dylan McKay downloaded his Facebook data to find out exactly how much was being collected only to discover that Facebook had logged all of his text messages and phone call history.

Ars Technica journalist Sean Gallagher reported the same startling discovery. I’m an iPhone user and checked my own Facebook data but found nothing had been logged. This is likely because the permissions affected the Android app and not the iOS app.

But when developers and tech journalists are getting surprised by how much of their data is on Facebook’s servers, we know that Facebook’s everlasting privacy problem isn’t getting any better. It actually seems to be getting worse.

The real issue seems to be less about what Facebook is collecting now or will collect in the future. It’s the realisation that you’ve handed over an accumulation of years and years of data — data you gave Facebook back when it first introduced that big blue login button on sites around the web, data you gave to app developers who turned around and scooped up your friends’ data, too.

Facebook has changed its data collection and retention polices so much over the years, it’s practically impossible to know what you’ve shared and to whom.

I’m not here to tell you to delete you Facebook profile. There are plenty of guides to using Facebook without giving away too much of your data, if that’s what you want to do. What I hope to do is add some clarity about why this week’s news has been so maddening.

It feels that way, I think, because it feels like data collection is not just out of control but has always been out of control. And that chaos is finally having real world consequences — perhaps the Trump presidency, but even more frightening is what could come. It’s not clear that the data from 50 million Facebook profiles acquired by Cambridge Analytica enabled that. We still don’t know how much or what kind of data is still out there in the wild, though.

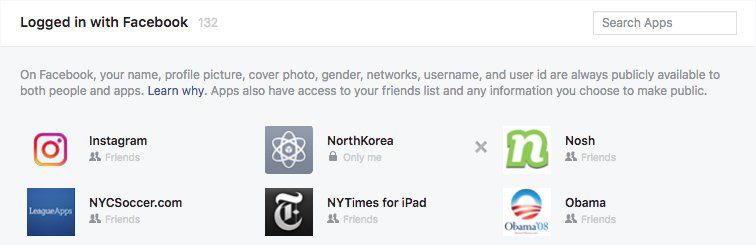

This in mind, I played a fun game a couple days ago called Revoke the App. What you do is, go into your Facebook settings, click the Apps icon on the left rail and then feast your eyes on up to a decade’s worth of giving your data to Facebook apps for free. To win the game, you have to revoke every app from accessing your Facebook data.

It’s a wild ride, too. I found an app called “NorthKorea” that didn’t have an icon and I have no memory of signing up for NorthKorea. Yet there I was, wondering what it had been collecting.

Facebook has taken steps to limit how much data app developers can collect. The company no longer lets app developers take your friends’ data without their permission. Mark Zuckerberg explained how this policy changed years ago several times in his initial response to this week’s crisis.

The permissions that enabled the political strategists at Cambridge Analytica to scoop up information from over 50 million Facebook users were once available to any app developer and now they’re not. That’s one slightly encouraging reminder, although it’s hardly proof that your data has ever been safe with Facebook.

Just look at who’s calling the shots. Mark Zuckerberg boldly declared that privacy was over back in 2010. “People have really gotten comfortable not only sharing more information and different kinds, but more openly and with more people,” Zuck told a crowd in San Francisco. “That social norm is just something that has evolved over time.”

That statement pissed a lot of people off — and for good reason. Facebook had already been on the defence over how it handled user data and flouted traditional privacy rules. A full two years before that “social norm” comment, Zuckerberg apologised for his company’s invasive Beacon ad program, which tracked users around the web without telling them, and he admitted that the company “did a bad job”.

The following year, Facebook outraged civil liberties groups with a new privacy policy that gave people less control over their what they could do with their data and made sensitive information like profile pictures, locations, and friend lists publicly available. These are just a couple of noteworthy uproars.

But all along the way, Zuckerberg’s responses to each Facebook scuffle with public opinion has basically amounted to the 33-year-old billionaire saying, “We’ll try harder.”

Anyone with a vague recollection of the history of Facebook will recognise the Cambridge Analytica situation as a violent symptom of something that’s plagued Facebook and its users for years: apathy. No matter what the company says, there’s a clear benefit to collecting as much data on its users as possible, and many users allow it. That’s how Facebook sells the most targeted adds and fills its coffers with unfathomable amounts of money.

In agreeing to terms, users often give up access to their data to Facebook and third-party developers without even realising it. Aleksander Kogan, the researcher who created the personality quiz app that ultimately led to Cambridge Analytica collecting data on over 50 million US voters, told the press this week that his team thought they “were doing something that was really normal.”

For whatever reason, people building Facebook apps and people using them just figured it was fine to agree to invasive data-gathering. Everybody was doing it back then. It was normal. We’re just now realising how horrifying normal can be.

The Cambridge Analytica scandal will run its course, and Facebook will change its policies (again). Mark Zuckerberg will keep telling us that Facebook will try harder. He might have to testify before Congress, but it remains to be seen whether that will lead to any new regulations for companies like Facebook.

People will keep using Facebook and Instagram and all the other apps in the family. All those apps will keep collecting data, and the data you’ve already surrendered will still be out there.

So that sense of betrayal you feel now might fade, but don’t let it. The only sensible response to this week’s revelations is the imperative that every internet user has to be mindful of what they’re surrendering when they sign up for free services like Facebook. You should also assume that your data could end up in the hands of bad actors. These days, that feels more likely than ever.

Inevitably, these vast quantities of Facebook data — and Instagram data and WhatsApp data — play a major role in a reshaping of how democracy works. The Cambridge Analytica debacle is just the beginning. We’ve been given a whiplash reminder that the internet can be a bad thing when you stop paying attention. So perk up, user.