Jeffrey Tibbetts prepped for implantation and scrubbed in, methodically sudsing up to his elbows, scraping the dirt from under his fingernails and scouring his hands with a rough brush to render his body sterile before donning a pair of beige latex surgical gloves.

Behind him, a twentysomething tea barista in a black baseball cap waited pensively, his left ring finger exposed from under a surgical drape, a tourniquet wrapped tightly around it. For months, an implanted magnet had been uncomfortably bulging out of the side of Zac Shannon’s finger. Tibbetts picked up a scalpel and began cutting, gently scraping away at the flesh until the incision was deep enough to expose the magnet. With the very steady hands of a practiced surgeon, he pulled out the tiny hunk of metal.

Tibbetts plopped another magnet into the finger, sutured it shut, and removed the tourniquet. The small wound began to gush blood.

“How do you feel?” Tibbetts asked Shannon.

“The removal was easier than I expected,” Shannon replied.

“Yeah,” said Tibbetts. “I purposefully upsold you on the pain.”

He exited the room, and took a long, deep drag from a vape.

Tibbetts is an ER nurse, but this was not a hospital. It was a procedure room in his home garage.

Every year, the bold and the brave make a pilgrimage here to California’s remote Tehachapi Mountains for Grindfest, a weekend dedicated to the merger of man and machine.

Grinders are hackers, but the hardware they aim to hack is the human body. They are transhumanist in the most literal sense. Grinders want to transcend human form. For many grinders, that means augmenting their bodies with cybernetic components – becoming cyborgs.

I came to Grindfest curious about how those on the extreme fringes of body hacking were incorporating technology into their lives and bodies. By the time the weekend was over, I had my own RFID chip implant – a small, potentially powerful electronic lump under the skin of my right hand.

Jeffrey Tibbetts removing a magnet implant from Zac Shannon’s finger. Photo: Kristen V. Brown

Like any clandestine subculture, the internet is the grinder movement’s true home, but Tibbetts’ house is where it occasionally manifests. Fellow grinders gather together here to break bread, exchange ideas, workshop implants, and in some cases get an implant or two themselves. As you might expect, there is also a rather copious amount of alcohol. Not to mention an annual electrified knife fight, in which rubber training knives are rigged give off an electrical charge upon contact with human flesh.

“It’s kind of like a mad scientist conference meets a family reunion,” Amanda Plimpton, who co-hosts Grindfest with Tibbetts, told me.

As a career nurse, Tibbetts is the community’s unofficial chief medic. Here, most people know him by his biohack.me forum handle, Cassox. Four years ago, he left Los Angeles and bought an 1980s-era prefab and four acres of land up a windy private road in the mountainous terrain that sits between the San Joaquin Valley and the Mojave Desert. His neighbours keep goats and grow apples. Tibbetts keeps a wet lab, an electronics workshop and a sterile room where he implants magnets and RFID chips and other cybernetic devices into people’s bodies.

Tibbetts doesn’t view an RFID implant as all that much different from a tattoo or a nose ring.

“People have been doing piercings for so long,” he said. “But the fact that we’re using technology when we’re doing this, people think of it as something different. It seems like, oh, this is probably some dangerous thing and, you know, these schmoes in a garage are cutting themselves or whatever. We actually do a lot of research and put a lot more effort into it than, you know, the body modification community would.”

To the grinder, it seems obvious that instead of carrying wallets and keys and IDs and mobile phones, we’ll one day interface with the world via microchips implanted under our skin.

Such ideas are not always welcomed warmly. For many of us, our smartphones may as well be attached to our bodies, but there is something about moving technology past the barrier of the skin that just gives people the heebie-jeebies. Once, when news of Grindfest made its way into local Facebook circles, Tehatchapi residents expressed mild outrage. Some have suggested that microchips could even be the Mark of the Beast, a sign described in Revelations to identify those who side with the Devil during apocalyptic times.

“People don’t like change,” Tibbetts told me. “This is obviously something that could change the world. And people fear that.”

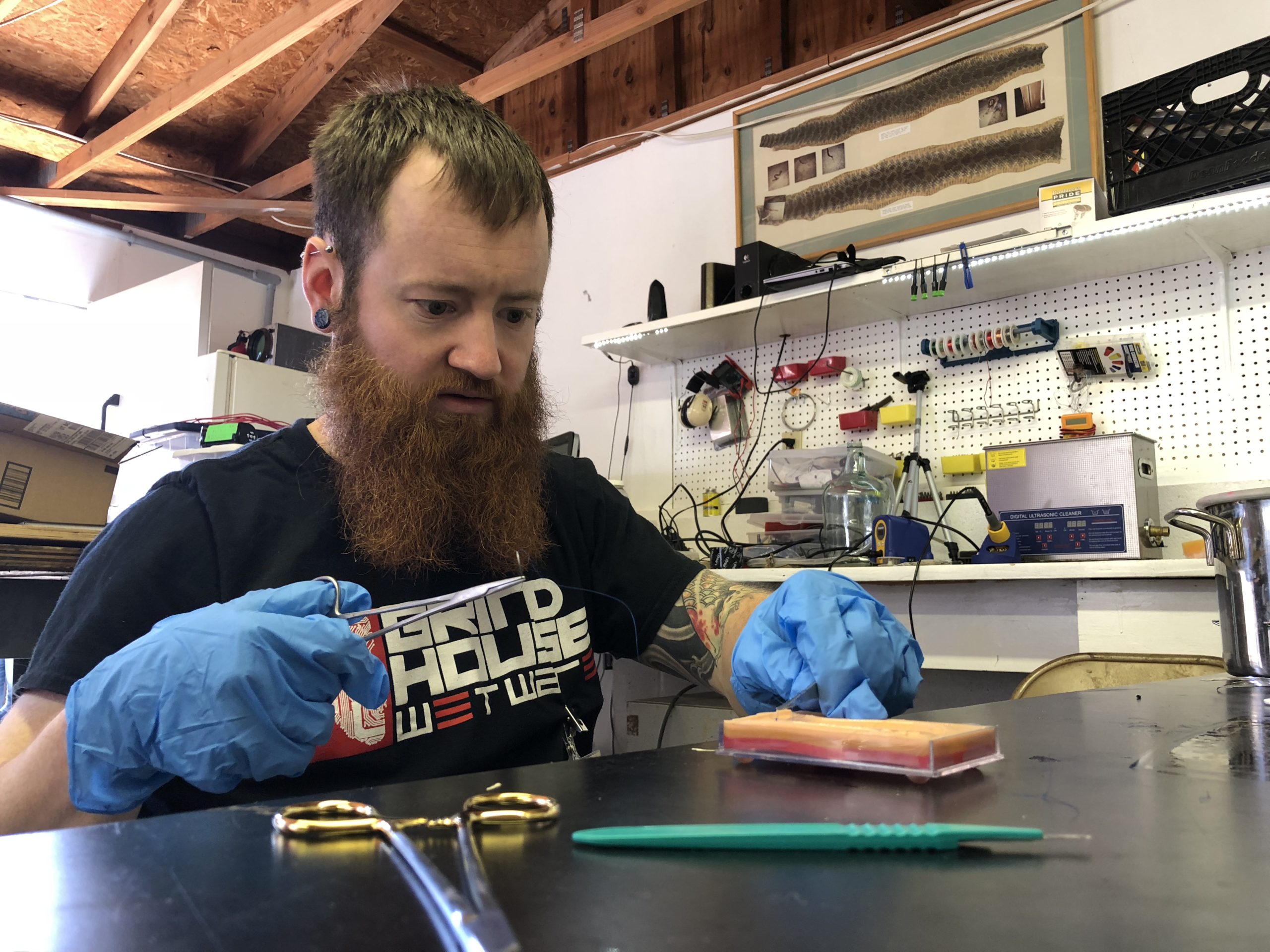

Justin Worst of Grindhouse Wetware practicing suturing.Photo: Kristen V. Brown

For most, British scientist Kevin Warwick was probably their first encounter with a non-fiction cyborg. Back in 1998, Warwick, then a professor of cybernetics at Reading University, became the world’s first bonafide “cyborg” when he had a radio transmitter chip implanted in his arm that allowed him to, among other things, turn on lights in his office by snapping his fingers. The implant only lasted nine days, but Warwick became a media fixture, dubbed “Captain Cyborg” by the press. He also mobilized a small group of do-it-yourself tech enthusiasts who, like Warwick, were interested in implanting electronics into their bodies. The term grinder came later, lifted from the comic book Doktor Sleepless, set in a near-future dystopia in which young people called “grinders” use extreme body modification to incorporate computers into their own bodies.

For decades, we’ve been implanting into the human body medical devices like pacemakers and IUDs. Warwick, though, pictured a future in which such implants might also be for fun and convenience.

That idea seems a lot less far-fetched than it did in 1998.

Last summer, a Wisconsin company called Three Square Market became the first US company to offer employees implantable NFC chips that let them open doors, buy snacks, log in to computers, and use office equipment like copy machines. Several companies in Europe had already tested similar programs. Several companies have sprung up out of the grinder scene, including Livestock Labs, which has translated some of the know-how gained hacking implants for humans into an implantable health tracker for cattle. And at the fifth annual Grindfest this year, the usual group of a few dozen grinders had expanded to 49. Among them: A U.C. Santa Cruz couple who had read about Grindfest and thought it sounded like a fun weekend getaway; a curious neighbour; and a 16-year-old science whiz from Phoenix, Arizona, Louis Anderson Jr., who came looking for human subjects for his high school science fair project. Anderson Jr. was supervised for the weekend by his dad.

Louis Anderson Sr., a lawyer, spent most of the weekend watching sports on his laptop while his son was busy in Tibbetts’ wet lab, concocting a coating for implants that he theorised could improve on the biocompatible coatings for implants available today. Anderson Jr. had already tested his idea in mice at his school’s microbiology lab.

Anderson Sr. said that when his son had pitched him on flying to California and spending the weekend in the middle of nowhere with a bunch of adults interesting in cybernetic body modification, he said yes, knowing it was an audience that would appreciate his son’s science obsession. He decided to go into it with an open mind. Still, he found himself a bit surprised when the carpool driver from the airport turned out to be Russ Foxx, a body modification artist with horns implanted in his forehead.

Some grinders expressed slight nervousness at having a lawyer in their midst. It’s unclear how agencies like the Food and Drug Administration and state health departments might view activities like implanting an untested biomedical coating into someone else.

But, Anderson Sr. said, it didn’t take him long to warm up to the grinder scene – though he wouldn’t allow his son get an implant that weekend.

“I like the hearts of people here. I really do,” he said. “They like my son, and I’m so appreciative that they are going to push his dreams.”

Louis Anderson, Jr. and Jeffrey Tibbetts in Tibbetts’ wet lab. Photo: Kristen V. Brown

Ryan O’Shea, the spokesperson for Grindhouse Wetware, which makes implants, said that he first heard about grinders four years ago, when he was working for a congressman on Capitol Hill. He read a story about Grindhouse, quit his job, and moved back home to Pittsburgh to convince Grindhouse founder and cyborg icon Tim Cannon to give him a job.

It was Friday evening, the first night of Grindfest, and people were still filtering in. O’Shea gestured to the crowd, which, while predominately white men, also many women, non-binary people, and an African-American father and son.

“Look at the wide spectrum of people here who have come to the conclusion that this is the future,” he said.

Lexi Linnell, a trans woman and the CTO at Livestock Labs, piped in.

“If you’re transgender, grinding actually has practical uses,” she said. For example, Linnell said, some people in the community had been exploring how to alter a gene involved in sex-regulation called DMTR1 that could theoretically turn testicles into something akin to external ovaries.

Over the weekend, one infamous biohacker, Rich Lee, would give a talk on his own sci-fi attempts to engineer his muscles by injecting them with myostatin, a gene to promote muscle growth. (It seems unlikely to work, but Lee is optimistic.)

Other grinders have implanted devices that emulate bioluminescence, that allow them to swipe on to public transit using only their hand, and that continuously measure body temperature. As the grinder community has grown and matured, there has recently been talk of reaching out to regulators and starting an academic journal dedicated to the topic – to make the community seem less fringe, and more accessible to outsiders.

“We have been using technology to transcend the human form for thousands of years,” said O’Shea. “It’s a feedback loop, where we create technology and then the technology recreates us. That cycle is accelerating. We can guide it.”

Louis Anderson, Jr. showing of the biocompatible coating he created for implants. The coating, shown in the middle of a long LED light, wound up not being implanted as planned over the weekend, because it did not appear safe enough.Photo: Kristen V. Brown

Still, we’re probably a long ways from being able to get an RFID implant at your local Claire’s.

Most implants simply aren’t that useful. Magnets are a popular implant, but all they do is allow the body to sense magnetic fields, a neat party trick without much practical use. (One grinder said she was able to diagnose a problem with her grandmother’s electric stove with the help of her magnet implant. Another incorporates the implants into her day job as a Vegas magician. In one trick, a magnet in her hand powers a lightbulb.) Plus, implanted magnets encounter problems so often that having one removed is practically a grinder right of passage. Using your hand to start your car or unlock your front door with an RFID is cool and perhaps even practical if you’re someone whose always losing their keys. But those chips have limited memory, and many systems are incompatible with one another, making it a guessing game what will work and what won’t.

James Newman, a salesman from Oregon, wanted to implant a chip from the key fob for his apartment complex into his hand. He hadn’t been able to successfully copy the code from the key fob onto one of the RFIDs he already had implanted, so his plan was to take the key fob apart and see whether the chip inside was something implantable. He spent the better part of Saturday trying to remove the chip from the fob’s plastic coating without ruining it. He had no idea whether, once implanted, the chip would work. (Newman reported back once home in Oregon: It did.)

“I lose things a lot,” Newman said. “But really there’s not a whole lot of added convenience here. The main reason I want to do this is just to see if I can really do it.”

O’Shea, despite being a spokesperson of sorts for the grinder community, doesn’t actually have any implants himself.

“I am purely interested in functional implants things that can extend my ability to do things,” he said.

So far, no implant that exists is quite functional enough for him.

“But look at the Wright brothers,” he said. “When they did the first Kittyhawk flights, they flew couple of hundred feet, a couple dozen feet off the ground in a few seconds. They put their lives on the line to travel for 15 seconds. Six decades later we were landing on the moon. What you’re seeing here is Kittyhawk.”

A moonshot, though, will require overcoming significant barriers. A major one is funding; at the moment, all this experimenting is paid for mostly out of the pockets of body-hacking enthusiasts. But there are technical obstacles, too. Much of the weekend programing was devoted to talks on things like safety and wound care and figuring out how to make better biocompatible coatings for implants.

And, of course, there is also the problem of public perception.

Grinder paraphernalia in Tibbetts’ garage. Image: Kristen V. Brown

A lack of obvious usefulness, though, is probably the movement’s greatest hurdle. I’m no stranger to subjecting myself to experimentation in the name of journalism, but for years, when grinders have asked me whether I’d consider getting an implant myself, I’ve balked at the idea. It just seemed silly. Unlocking my apartment door with my hand sounds cool, but setting up an NFC-compatible lock honestly seems like more of a hassle than just remembering my keys.

Over the weekend, I quizzed every grinder I spoke to about what sort of killer implant they thought would bring cybernetics into the mainstream. Answers generally fell into two camps: health or payments.

It was roughly the argument of the Apple Watch. The Apple Watch didn’t exactly blow up like the iPod or the iPhone. Most people just don’t need that much power on their wrist. But with healthcare applications, like the ability to monitor heart conditions, the Watch may have finally found its niche.

“It’s going to be a slow process,” said O’Shea. “But when there are stories of lives being saved by some kind of health implant, people will get onboard.”

Still, infected by the enthusiasm of all the grinders I’d met, I decided to give it a try. On the last day of Grindfest, I slipped into Tibbetts’ old repurposed dental chair and gritted my teeth as he prepared to plant a tiny RFID chip into the webbing between my thumb and forefinger. Tibbetts pinched my skin and plunged the needle in, moving it around under my skin until he had placed it in an ideal location, an inch or so down my hand toward my wrist. It hurt less than any one of my tattoos. Becoming a cyborg was downright anticlimactic.

A few weeks later, I still haven’t thought of a great way to use my newfound cybernetic body part. I’m not sure something useful will come anytime soon.