Stanley Kubrick’s influential classic 2001: A Space Odyssey turns 50 this week. One of its most enduring qualities is how open to interpretation it is – over the years, the enigmatic film has inspired some fascinating (and/or delightfully batshit crazy) theories about what it all means. This is exactly what the director intended.

In an oft-cited 1969 interview with author Joseph Gelmis, Kubrick was prompted to explain the film’s ending, which he agreed to do only in terms of the plot:

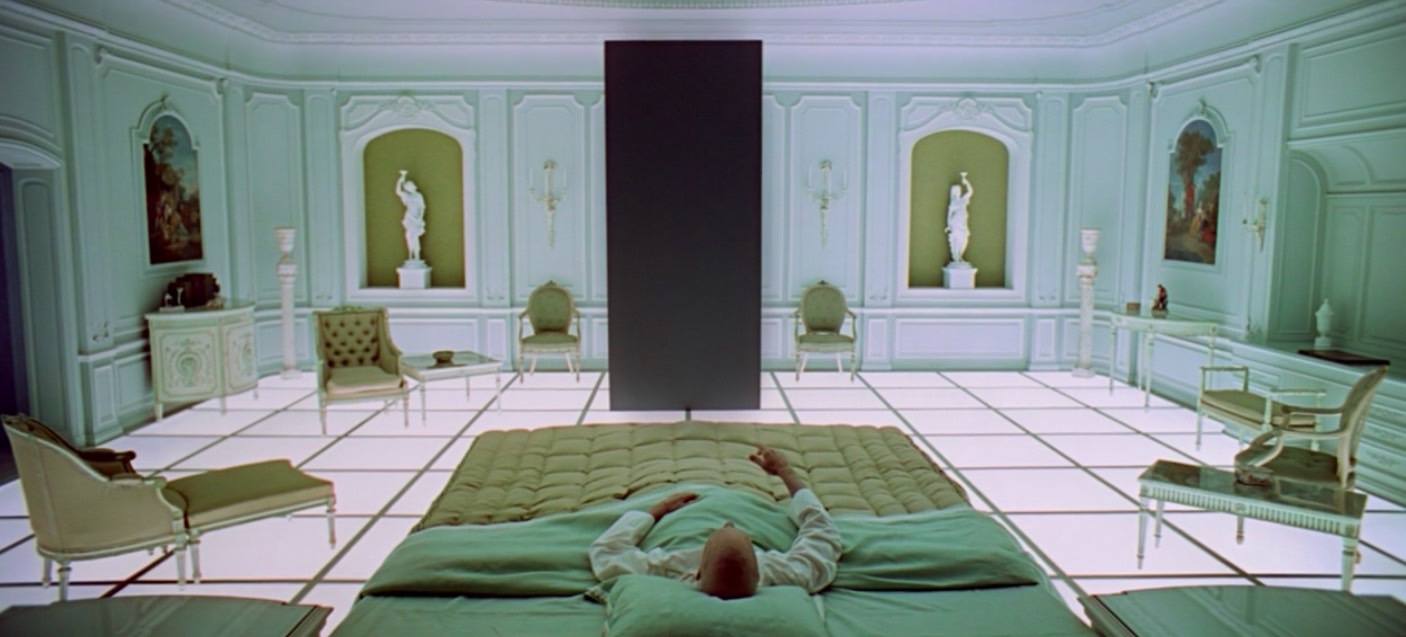

When the surviving astronaut, Bowman, ultimately reaches Jupiter, this [alien] artifact sweeps him into a force field or star gate that hurls him on a journey through inner and outer space and finally transports him to another part of the galaxy, where he’s placed in a human zoo approximating a hospital terrestrial environment drawn out of his own dreams and imagination. In a timeless state, his life passes from middle age to senescence to death. He is reborn, an enhanced being, a star child, an angel, a superman, if you like, and returns to earth prepared for the next leap forward of man’s evolutionary destiny.

He refused to dig any deeper. Thanks to 2001's incredible ambiguity, “the film becomes anything the viewer sees in it. If the film stirs the emotions and penetrates the subconscious of the viewer… then it has succeeded” said Kubrick in the same interview. This could apply to other titles in Kubrick’s filmography; , Rodney Ascher’s documentary about perceived hidden meanings in The Shining, as explained by mega-fans who’ve studied that film very, very closely. But 2001 has, of course, sparked its own obsessive interpretations about what it all means. .

That aspect ratio though.

The monolith represents a movie screen

Rob Ager, known on YouTube as Collative Learning, has made several videos offering specific analysis of various films, and his content is quite Kubrick-heavy. Among Ager’s most popular clips is a two-part investigation titled “2001: A Space Odyssey – Meaning of the Monolith Revealed” (part one here; part two here). After giving some background on the monolith’s differing uses in Kubrick’s film and Arthur C. Clarke’s accompanying novel, and pointing out the 90-degree camera angles used before and during the “Stargate” sequence, he gets to his main thesis at the end of part one:

The monolith represents the screen on which the viewer is watching the film. Basically, 2001 was funded as a space-race propaganda film by NASA and IBM and other corporations. And Kubrick has used the cryptic, upright presentation of the monolith to hide the simple clue, which when discovered, demolishes the artificial alien intelligence narrative. The film itself is the monolith, an “advanced television teaching machine,” as Kubrick put it, and the apes and astronauts puzzling over the monolith represent us, the confused audience, who need only get up from our seats and touch the screen to confirm to ourselves that the space-race propaganda narrative isn’t real. It’s an illusion. It’s just a movie.

In the second video, Ager further examines all the times shapes mimicking the monolith appear throughout the film – from the more obvious (the white, rectangular walls in in the briefing room when Dr. Heywood Floyd first arrives at the moon base) to the more subtle (Dr. Floyd’s rectangular food tray as it floats in zero gravity). Truly, there are a lot once you start looking for them. He also points out the many sequences emphasising rotation, which is what you’d need to do to turn the upright monolith into something resembling a movie screen – and even looks at other Kubrick films that also reference the iconic rectangle.

Got any ham?

The whole movie is about food

Why does one of the greatest science fiction movies of all time have so much eating in it? The apes have a feast once they figure out how easy mealtime can be with a bone-weapon in hand. Then, after a space-station breakfast in the Howard Johnson Earthlight Room (which unfortunately happens off-screen), we see Dr. Heywood Floyd sipping on carefully packaged liquid food – baby food, really – while he’s travelling from the station to the moon. Once Dr. Floyd is on the moon, literally en route to see the greatest discovery in the history of humankind, he takes the time to gleefully gobble a sandwich that, we’re told, tastes “something like” chicken. Then, in the film’s next sequence, we see the Jupiter astronauts serving themselves trays of grossly colourful food-mush as part of their daily routine. Finally, there’s Old Dave’s fancy meal, complete with silver service and a tablecloth, once he reaches his final destination. Kubrick never did anything that wasn’t completely intentional, so you have to assume 2001's insanely high number of food-related scenes is no accident. Nor can you ignore the fact that every time someone eats, something important happens immediately afterward, as when Dr. Floyd, still digesting his crustless snack, first lays eyes on the monolith.

The theory that 2001 is actually all about food – which first came to my attention in this wonderful essay by Josh Ronsen – is my personal favourite of the bunch. And once it’s lodged in your brain, you’ll never watch the movie without thinking of it… or experiencing a weird longing for a faux-chicken picnic sandwich on the moon.

Quite honestly, I wouldn’t worry myself about that.

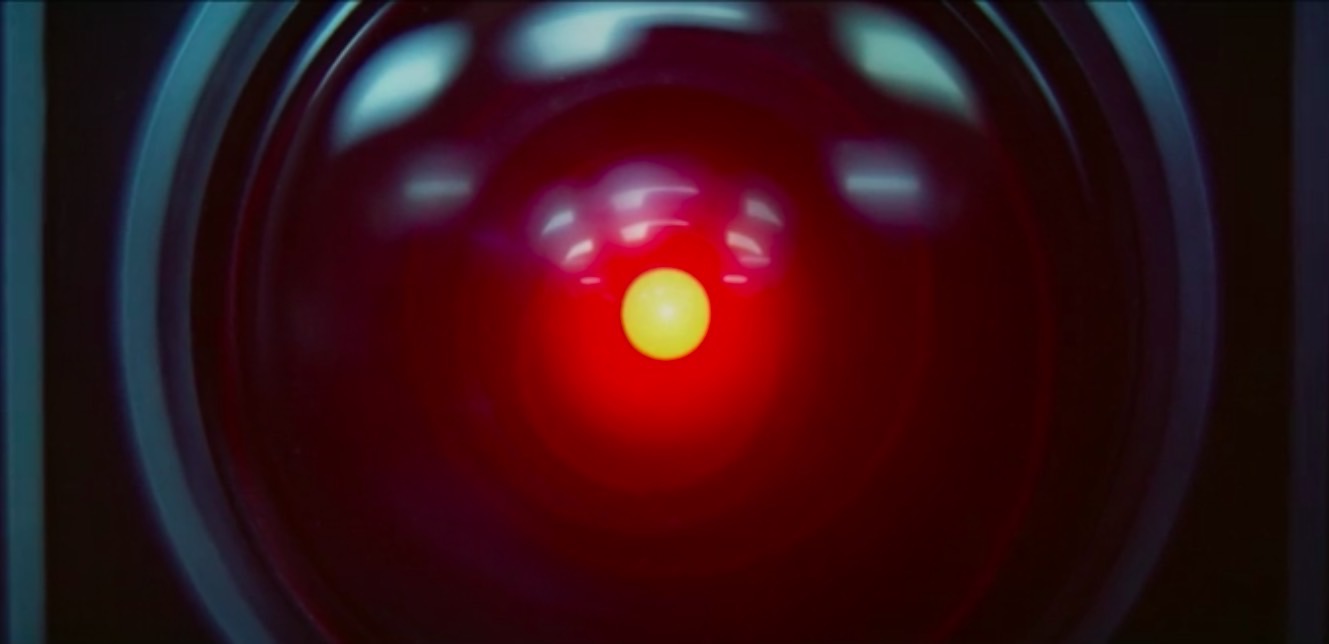

HAL 9000 is queer

Like the food theory discussed above, io9 has delved into the “HAL can be read as gay” idea before, with this excerpt from cultural critic Mark Dery’s 2012 book I Must Not Think Bad Thoughts: Drive-by Essays on American Dread, American Dreams. The insightful piece is well worth reading in full, but it begins with Dery’s assertion that 2001's most memorable character, supercomputer HAL 9000, fails the Turing Test — except not in the way that you’re thinking:

Not Alan Turing’s classic blindfold test for artificial intelligence, which the ultra-intelligent machine could pass “with ease” as Arthur C. Clarke notes in the novel on which Stanley Kubrick based his movie, but the test that Turing himself failed (albeit deliberately): that of passing for straight.

Dery’s evidence in favour of HAL being gay includes certain artistic choices, like the computer’s voice:

Kubrick biographer Vincent LoBrutto notes that the director was pleased with the “patronizing, asexual quality” [Shakespearean actor Douglas Rain] gave HAL, but one man’s condescension is another man’s cattiness; balanced on the knife edge between snide and anodyne, HAL’s sibilant tone and use of feline phrases like “quite honestly, I wouldn’t worry myself about that” contain more than a hint of the stereotypic bitchy homosexual. Clarke himself has acknowledged that HAL’s voice betrays “a certain ambiguity,” sexually.

But more compellingly, the author investigates HAL’s place in the film, which is populated almost entirely by men, and specifically as part of the Discovery‘s all-male crew. Following Turing’s speculation that a super-intelligent computer like HAL would indeed have the capacity to be “charmed by sex,” Dery wonders: “How many months in space with nothing to do but stomp [Frank] Poole in chess and fiddle with the ship’s radio dish before even the Discovery’s astronauts begin to look desirable?” The ultimate idea, and this is boiling it down quite a lot, is that HAL has taken a particular liking to Dave, and may even be jealous after imagining that there’s a more-than-professional relationship between Dave and Frank. “Is Frank’s murder the cold-blooded elimination of a rival for Dave’s affections?” Dery asks, pointing to the old-timey love song that HAL croons – “Daisy Bell (Bicycle Built for Two)” – while Dave is literally shutting him down.

That’s really just the briefest summary of Dery’s thoughtful take on the subject. It’s worth noting that unlike the other theories on this list, his investigation hinges on Clarke – whose book was more of a companion to the film than its literal source material – than it does on Kubrick, whose cinematic vision was the main architect of 2001, the movie. And while Dery ultimately admits that “HAL’s sexuality is destined to remain an open question,” he does include an afterword that he sent a version of the essay to Clarke (who, Dery notes, famously preferred not to openly discuss his own sexuality). Of Dery’s theory about HAL, Clarke wrote: “I can’t confirm or deny your speculations. Who knows what goes on down in the subconscious?” That’s a point Kubrick would no doubt agree with.

The film is tied to NASA’s scheme to fake the moon landing

This one isn’t really about what’s contained in 2001, but it’s so bizarre we didn’t want to leave it out. It branches off one of the most popular conspiracy theories of the 20th century: American astronauts never actually walked on the moon and the whole thing was an elaborately conceived Cold War charade. The release of 2001 just a year prior to Apollo 11's lunar mission seems to have sparked the idea that Kubrick was hired by NASA to secretly fake and film the astonishing “small step for man” on an earthly soundstage. Of course, this has been widely derided as a hoax – Snopes has one of its trademark takedowns on file, but the snappiest response we’ll ever see came from Kubrick’s daughter, Vivian (who happens to have a cameo as Dr. Heywood Floyd’s young daughter, glimpsed via video phone, in 2001), who tweeted this a few years back:

Re: Faked Moon Landings

Many people have asked me about this. And this feels like the right time to respond … pic.twitter.com/UVlNFofFW8— Vivian Kubrick (@ViKu1111) July 5, 2016

The story may indeed be A GROTESQUE LIE, but that hasn’t stopped it from capturing imaginations over the years. It was even the basis for a 2016 comedy, Moonwalkers – though that version of the yarn swaps in a different director when Master Kubrick proves elusive.