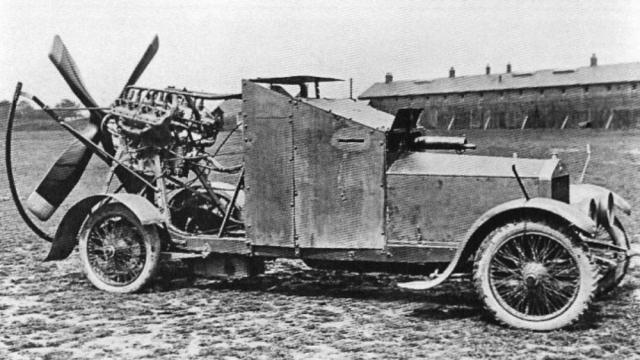

Scanned from The World’s Worst Weapons (From Exploding Guns to Malfunctioning Missiles) by Martin J. DoughertyImage: British Royal Air Force

Every so often, there’s a car so wild and such a hilarious failure that history tries to dance around it. The records of these automotive mishaps are skimmed over with little more than an awkward, “yeah, um, also we kinda messed up – but look at the good things instead!”

The Sizaire-Berwick armoured car… is definitely one of those cars.

What started off as a promising auto company was blasted by the Great War. The French engineering brothers Maurice and Georges Sizaire created a chassis, and British F. W. Berwick & Company added the body in London in 1912: thus they created a car of unprecedented speed and long-distance endurance while also patenting a handful of new technologies. They started producing and selling cars the following year, earning a reputation of being a fast but high-quality vehicle.

And then that “war to end all wars” thing happened. Which threw a monkey wrench into Sizaire-Berwick’s plans to keep developing cars for the everyday human.

Production basically got taken over by the government, and the last chassis in the plant were driven to the coast. They hastily fit the chassis with bodies intended for military use, and the production site in Highgate swapped over to producing wartime vehicles.

The need for vehicles led to some… interesting innovative choices. Namely, someone decided to ask “so, like, what if we powered an armoured car with a propeller?” and nobody stopped to realise that this is the exact kind of Frankenstein creature you’d create with crayons at age five when you realised that aeroplanes are cool and cars are cool so what about a car that looks like an aeroplane???

In all fairness, the propellor was supposed to help the armoured car navigate sandy terrains, which is something that early 20th century cars weren’t all that great at. Unfortunately… Sizaire-Berwick turned out to not be all that great, either.

See, the expedited production timeline meant that there wasn’t a ton of thought put into the development of the cars from a functional perspective. So it just made sense to throw a 110-horsepower plane engine onto the back of a chassis, because why the hell not? If cars can’t easily cruise over sand, maybe strapping an aircraft engine will just… make it too fast to not drive over the sand.

Nobody thought about how to preserve the longevity of that engine, though. They just kinda… strapped it to the chassis, wiped their hands, and called it a day. The whole engine was almost entirely exposed. So not only was it hanging out there as a nice target for enemy fire from literally any direction, but it was also exposed to sand. That thing that deserts are made of? Yeah. It turns out that an exposed engine + propellers + sand everywhere = A Real Bad Time.

On the bright side, it wasn’t like they’d deployed a whole fleet of these wind wagons out into the thick of battle only to realise, hey, this was a really terrible idea! They created one prototype, and that’s all it took before someone finally pointed out that there was no feasible way this vehicle designed for the desert would ever actually function in the desert.

So the armoured car was shelved, and Sizaire-Berwick factory turned to different things. Motorsport Magazine lists a whole wealth of their wartime accomplishments:

On various chassis of other makes, mainly heavy Leylands, were built such vehicles as living wagons for anti-aircraft gun crews, machine-gun and searchlight lorries, travelling photographic darkrooms, telephone exchanges, workshops, and caravans which were almost miniature hotels on wheels.

But photos of the armoured half-plane half-tank still exist out there in the depths of the Internet to keep us all a little humble when we start thinking our ideas are impossibly great.