Fake news sucks, and as those eerily accurate videos of a lip-synced Barack Obama demonstrated last year, it’s soon going to get a hell of a lot worse. As a newly revealed video-manipulation system shows, super-realistic fake videos are improving faster than some of us thought possible.

Left: Real footage of Vladimir Putin. Right: Simulated video using new Deep Video Portraits technology. GIF: H. Kim et al., 2018/Gizmodo

The SIGGRAPH 2018 computer graphics and design conference is scheduled for August 12 to 16 in Vancouver, British Columbia, but we’re already getting a taste of the jaw-dropping technologies that are set to go on display.

One of these systems, dubbed Deep Video Portraits, shows the dramatic extent to which deepfake videos are improving. The manipulated Obama video from last year, developed at the University of Washington, was pretty cool, but it only involved facial expressions, and it was pretty obviously an imitation. The exercise served as an important proof-of-concept, showcasing the scary potential of deepfakes – highly realistic, computer-generated fake videos. Well, that future, as the new Deep Video Portraits technology shows, is getting here pretty damned fast.

Video abstract of the new technology, Deep Video Portraits. (YouTube)

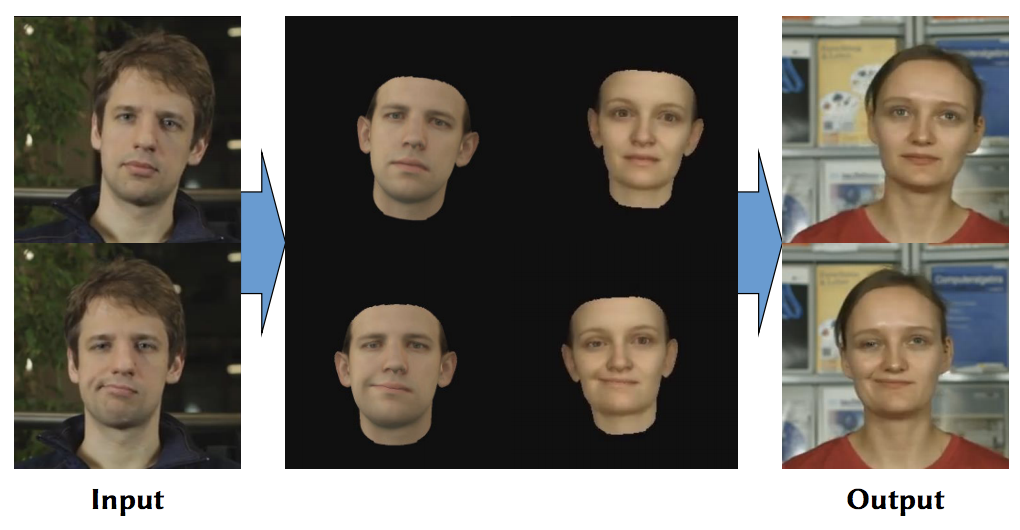

The new system was developed by Michael Zollhöfer, a visiting assistant professor at Stanford University, and his colleagues at Technical University of Munich, the University of Bath, Technicolor, and other institutions. Zollhöfer’s new approach uses input video to create photorealistic re-animations of portrait videos. These input videos are created by a source actor, the data from which is used to manipulate the portrait video of a target actor. So for example, anyone can serve as the source actor and have their facial expressions transferred to video of, say, Barack Obama or Vladimir Putin.

The new system enables “full control over the target by transferring the rigid head pose, facial expression and eye motion with a high level of photorealism.” Here, a source actor (the input) is used to manipulate a portrait video of a target actor (the output). Image: H. Kim et al., 2018

But it’s more than just facial expressions. The new technique allows for an array of movements, including full 3D head positions, head rotation, eye gaze, and eye blinking. The new system uses AI in the form of generative neural networks to do the trick, taking data from the signal models and calculating, or predicting, the photorealistic frames for the given target actor. Impressively, the animators don’t have to alter the graphics for existing body hair, the target actor body, or the background.

Comparison to previous approaches. Notice how the background warps in the 2017 study. GIF: H. Kim et al., 2018/Gizmodo

Secondary algorithms are used to correct glitches and other artifacts, giving the videos a slick, super-realistic look. They’re not perfect, but holy crap they’re impressive. The paper describing the technology, in addition to being accepted for presentation at SIGGRAPH 2018, was published in the peer-reviewed science journal ACM Transactions on Graphics.

Left: Real footage of UK Prime Minister Theresa May. Right: Simulated video using new Deep Video Portraits technology. GIF: H. Kim et al., 2018/Gizmodo

Deep Video Portraits now presents a highly efficient way to do computer animation and to acquire photorealistic movements of pre-existing acting performances. The system, for example, could be used in audio dubbing when creating versions of films in other languages. So if a film is shot in English, this tech could be used to alter the lip movements to match the dubbed audio in French or Spanish, for example.

Left: Real footage of Barack Obama. Right: Simulated video using new Deep Video Portraits technology. GIF: H. Kim et al., 2018/Gizmodo

Unfortunately, this system will likely be abused – a problem not lost on the researchers.

“For example, the combination of photo-real synthesis of facial imagery with a voice impersonator or a voice synthesis system, would enable the generation of made-up video content that could potentially be used to defame people or to spread so-called ‘fake-news’,” writes Zollhöfer at his Stanford blog. “Currently, the modified videos still exhibit many artifacts, which makes most forgeries easy to spot. It is hard to predict at what point in time such ‘fake’ videos will be indistinguishable from real content for our human eyes.”

Sadly, deepfake tech is already being used in porn, with early efforts to reduce or eliminate these invasive videos proving to be largely futile. But for the burgeoning world of fake news, there are some potential solutions, like watermarking algorithms. In the future, AI could be used to detect fakes, sniffing for patterns that are invisible to the human eye. Ultimately, however, it will be up to us to discern fact from fiction.

“In my personal opinion, most important is that the general public has to be aware of the capabilities of modern technology for video generation and editing,” writes Zollhöfer. “This will enable them to think more critically about the video content they consume every day, especially if there is no proof of origin.”