Our oceans are brimming with microscopic phytoplankton — plant-like organisms that contribute significantly to marine diversity. Tiny though they are, these sea critters, when infected with a particular virus, may influence atmospheric processes such as cloud formation, according to new research.

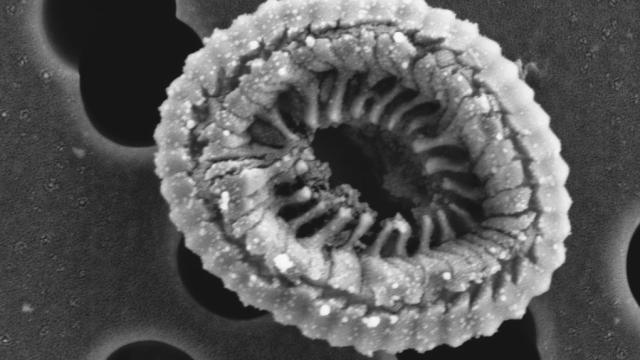

A ubiquitous, bloom-forming phytoplankton known as Emiliania huxleyi is plagued by a virus known as EhV. Back in 2015, scientists from the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel discovered that EhV causes E. huxleyi to shed and release pieces of its shell into the air, leading to further infection.

In an update to this research, the same team has now found that these airborne emissions, known as coccolith, are released in such vast quantities that infected phytoplankton are likely influencing the weather. In fact, so much coccolith is being released into the sky that it has to be classified as a sea spray aerosol, or SSA. This latest research was published today in iScience.

Sea spray aerosols waft up into the atmosphere when bubbles burst in the ocean, and they can blanket upwards of 70 per cent of the atmosphere. Individual SSA particles contribute to cloud condensation and act as a surface for chemical reactions. Because they’re so reflective, they can also help determine how much solar energy is absorbed by the Earth and radiated back into space.

The new research, led by Weizmann Institute earth scientist Miri Trainic, involved creating a miniature coccolith-producing system in the lab. In the real world, phytoplankton can cover thousands of square kilometres of ocean surface, but by creating a small model, the scientists were better able to quantify the effects of EhV on E. huxleyi and extrapolate from there.

The researchers were surprised by the sheer quantity of particles produced, their high density, and their large size.

“Airborne coccolith surface area and volume increased substantially in our lab system during viral infection compared to sea salt particles, which are the most ubiquitous primary marine aerosol component,” Trainic told Gizmodo. “In fact, the surface area of coccoliths reached up to 3.5 times higher than that of sea salt aerosol surface area.”

Trainic says the viral infection of the phytoplankton induces massive coccolith production in the seawater, which leads to large coccolith emissions. Because these particles are relatively large, they can become the dominant component in terms of surface area and volume of all marine SSAs, she said.

Though the researchers were unable to prove it in a laboratory experiment, they suspect the enormous quantities of SSAs released by these phytoplankton influence the weather, especially cloud formation.

“It is well known that particles the size of coccoliths participate in cloud formation,” said Trainic. Moreover, once in the atmosphere, coccoliths can react chemically with other aerosols and water droplets in ways that may help increase water condensation within clouds, she said.

Looking ahead, the researchers would like to observe these blooms and their SSA emissions in the real world.

“The laboratory does not provide natural conditions and can never fully mimic them,” Trainic said. “While we are able to perfectly monitor the Emiliania Huxleyi-EhV interaction in the lab, we cannot reproduce the complexity of a natural population, nor can we reproduce the environmental conditions in the ocean.”

As a final note, this study could be of relevance to geoengineers in search of technological solutions to human-caused climate change and global warming. But it’s also a cautionary tale, one that speaks to the high degree of complexity involved in climate, and the important role played by biological processes. There’s still a lot to learn about our planet and what makes it tick.

[iScience]