A pair of new studies published Thursday are the latest to suggest probiotic supplements might not be as universally useful as their proponents believe.

In a series of experiments involving mice and healthy human volunteers, the Israeli researchers found that probiotics only sometimes do what they’re advertised to do: change the makeup of our gut’s bacterial environment, known as the microbiome.

They also found that people who take probiotics after antibiotic therapy – a common practice meant to help restock the gut with healthy bacteria – aren’t necessarily better off, either. Rather than speed up the process, people using probiotics actually took longer to have their microbiome return to normal than did people who took nothing at all, sometimes as long as five months after they stopped taking them. The papers are published in the journal Cell.

“[O]ur results suggest that the empirical habit of consuming probiotics after antibiotic use may not be completely harmless as was previously thought, and in fact may be associated with long-term consequences,” senior author Eran Elinav, an immunologist and head of the Elinav lab at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, told Gizmodo via email.

This delay in restoring a healthy microbiome, he added, could further raise a person’s risk of health problems thought to be linked to a chronically imbalanced microbiome, such as obesity, allergy, and other inflammatory disorders.

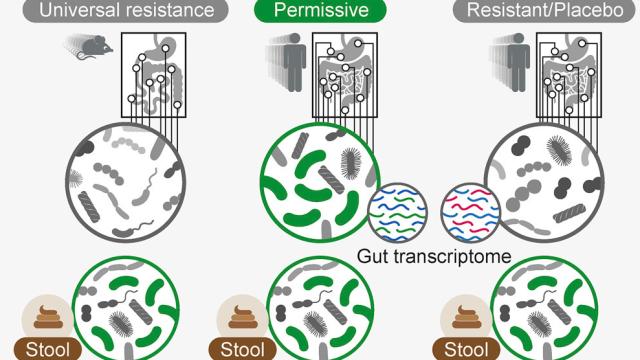

Elinav’s research isn’t the first to show that probiotics aren’t always what they’re chalked up to be. But he said his team’s approach was much more extensive than previous studies. In the first experiment, for instance, they asked 15 adult volunteers to undergo colonoscopies before, during, and after taking a probiotic twice a day that had 11 different strains of probiotics (or a placebo), over the course of three weeks. That allowed the team to directly study their microbiomes. At the same time, the volunteers also regularly gave stool samples.

Scientists studying probiotics have largely relied on testing stool samples to figure out how probiotics could be affecting the gut. But the team’s results suggest this might be a mistake. The volunteers’ stool samples did show the bacteria found in the probiotics were digested and even sometimes grew, suggesting they had interacted with the gut in some way. But the colonoscopy results often showed little to no trace of the specific bacteria in the gut, and were largely indistinguishable from the control group.

The gut microbiomes of healthy mice that consumed probiotics seemed to resist the new bacteria strains entirely, preventing them from colonizing the gut. (Probiotics did colonize mice that were bred to be germ-free.) In humans, though, it was more complicated. There were some people whose bodies did “permit” the bacteria to colonize the gut, and in these people, there was evidence the bacteria had temporarily altered how genes in the gut were expressed, indicating they had a real effect. But importantly, stool samples couldn’t tell apart these “permitters” from people who were wholly unaffected, meaning any research solely based on this method could be fatally flawed.

In the second study, probiotics did colonize the guts of people who had first taken antibiotics. But this colonization seemed to destabilize the microbiome much more than simply leaving the gut alone, leading to delays in restoring it back to normal.

The studies, Elinav is careful to point out, weren’t intended to settle the question of whether probiotics can or can’t provide health benefits, either by using them while healthy or to promote a healthy gut after using antibiotics.

“However, our studies do demonstrate in a very direct way that probiotic effects in healthy conditions are personalised and transient at best, and if you take a probiotic that you buy at your local supermarket, you have no way of knowing whether it would pass from one end to the other or colonize your gut, where it may (or may not) induce health effects,” he said.

The silver lining, he said, is that his team was able to predict who would accept these probiotics, relying on markers like a person’s initial microbiome layout, their genetic makeup, and the specific strains in the probiotic. That finding, along with other research his team has conducted, raise the possibility of developing personalised probiotic therapies that can affect the human gut as intended. These therapies could not only presumably answer the important question of whether probiotics are worth the effort, but prevent probiotics from harming the microbiome when taken with antibiotics.

Of course, both of these studies need to be followed up on, using larger and more diverse groups of people. Children’s microbiomes, for instance, might react differently to probiotics, as might people who are actively sick with a gut disorder.

There was another interesting wrinkle found in the second study. People who took probiotics with antibiotics had worse microbiomes than a control group, but it was actually people who had faecal transplants (sourced from their own stool samples provided earlier) whose gut microbiomes recovered the quickest from antibiotics, compared to a control group. That suggests faecal transplants might also someday be an useful, if stomach-churning way to keep our guts healthy after taking powerful antibiotics.