Grass trees (genus Xanthorrhoea) look like they were imagined by Dr Seuss. An unmistakable tuft of wiry, grass-like leaves atop a blackened, fire-charred trunk. Of all the wonderfully unique plants in Australia, surely grass trees rank among the most iconic.

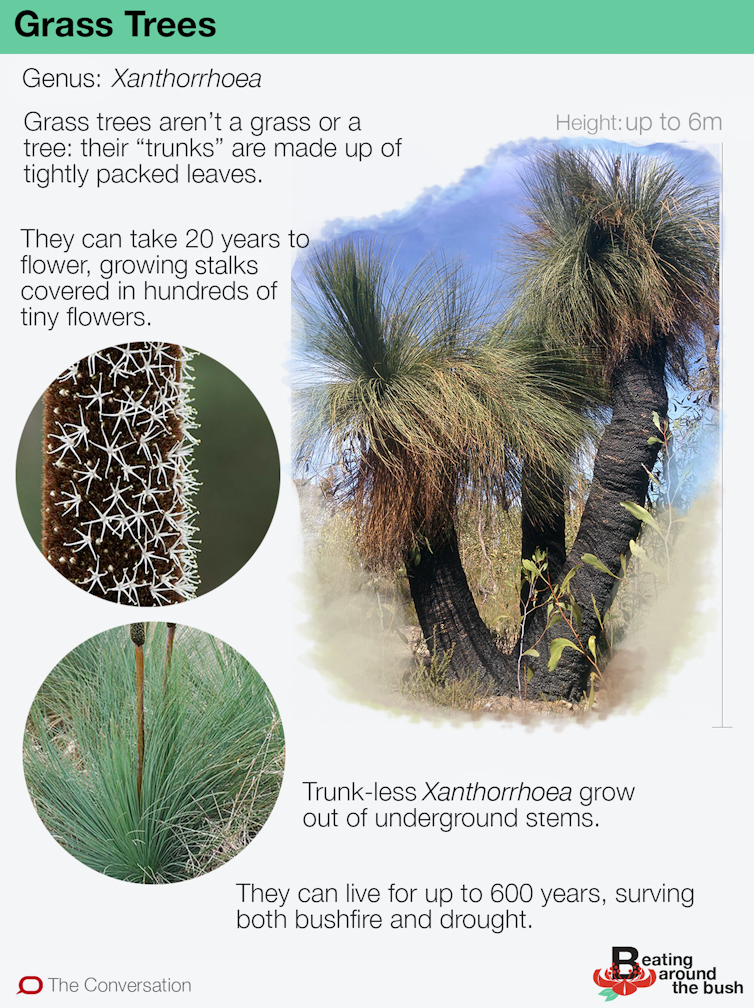

The common name grass tree is a misnomer: Xanthorrhoea are not grasses, nor are they trees. Actually, they are distantly related to lilies. Xanthorrhoea translates to “yellow flow”, the genus named in reference to the ample resin produced at the bases of their leaves.

All 28 species of grass tree are native only to Australia. Xanthorrhoea started diversifying around 24-35 million years ago – shortly after the Eocene/Oligocene mass extinctions – so they have had quite some time to adapt to Australian conditions.

Wander through remnant heathland or dry sclerophyll forest, particularly throughout the eastern and south-western regions of Australia, and you’ll likely find a grass tree.

CC BY

Perfectly adapted to their environment

Xanthorrhoea are perfectly adapted to the Australian environment, and in turn, the environment has adapted to Xanthorrhoea. Let’s start the story from when a grass tree begins as a seed.

After germination, Xanthorrhoea seedlings develop roots that pull the growing tip of the plant up to 12cm below the soil surface, protecting the young plant from damage. These roots quickly bond with fungi that help supply water and minerals.

Once the tip of the young plant emerges above ground, it is protected from damage by moist, tightly packed leaf bases, although shoots may develop if it is damaged. The leaves of Xanthorrhoea are tough, but they lack prickles or spines to deter passing herbivores. Instead, they produce toxic chemicals with anaesthetising effects.

All Xanthorrhoea are perennial; some species are estimated to live for over 600 years. Most grow slowly (0.8–6 cm in height per year), but increase their rate of growth in response to season and rainfall. The most “tree-like” species grow “trunks” up to 6 metres tall, while trunkless species grow from subterranean stems.

Grass trees don’t shed their old leaves. The bases of their leaves are packed tightly around their stem, and are held together by a strong, water-proof resin.

As the old leaves accumulate, they form a thick bushy “skirt” around the trunk. This skirt is excellent habitat for native mammals. It’s also highly flammable. However, in a bushfire, the tightly-packed leaf bases shield the stem from heat, and allow grass trees to survive the passage of fire.

John Patykowski, Author provided

Xanthorrhoea can recover quickly after a fire thanks to reserves of starch stored in their stem. By examining the size of a grass tree’s skirt, we can estimate when a fire last occurred.

It can take over 20 years before a grass tree produces its first flowers. When they do flower it can be spectacular, producing a spike and scape up to four metres long advertising hundreds of nectar-rich, creamy-white flowers to all manner of fauna. Flowering is not dependent on fire, but it stimulates the process. The ability of grass trees to resprout after fire and quickly produce flowers makes them a vital life-line for fauna living in recently-burnt landscapes.

Grass trees provide food for birds, insects, and mammals, which feast on the nectar, pollen, and seeds. Beetle larvae living within the flower spikes are a delicacy for cockatoos. Invertebrates such as green carpenter bees build nests inside the hollowed out scapes of flowers. Small native mammals become more abundant where grass trees are found, for the dense, unburnt skirt of leaves around the trunk provides shelter and sites for nesting.

Indigenous use of grass trees

For Indigenous people living where grass trees grow, they were (and remain) a resource of great importance.

The resin secreted by the leaf-bases was used as an adhesive to attach tool heads to handles and could be used as a sealant for water containers. This valuable and versatile resin was an important item of trade.

The base of the flowering stem was used as the base of composite spear shafts, and when dried was used to generate fire by hand-drill friction. The flowers themselves could be soaked in water to dissolve the nectar, making a sweet drink that could be fermented to create a lightly alcoholic beverage.

When young, the leaves of subspecies Xanthorrhoea australis arise from an underground stem which is seasonally surrounded by sweet, succulent roots that can be eaten. The soft leaf bases also were eaten, and the seeds were collected and ground into flour. Edible insect larvae residing at the base of grass tree stems could be collected. Honey could be collected from flower stems containing the hives of carpenter bees.

European exploitation

European settlers were quick to clue onto the usefulness of the resin , using it in the production of medicines, as a glue and varnish, and burning it as incense in churches. It was even used as a coating on metal surfaces and telephone poles, and used in the production of wine, soap, perfume and gramophone records.

John Patykowski, Author provided

Resin can easily be collected from around the trunk of plants, but early settlers used more destructive methods, removing whole plants on an industrial scale. The resin was exported worldwide; during 1928-29, exported resin was valued at over £25,000 (equivalent to A$2 million today!).

We still have much to learn about grass trees. Current research indicates an extract from one subspecies can be used as a cheap, environmentally-friendly agent to synthesise silver nanoparticles that are useful for their antibacterial properties.

Threats to grass trees

Many of the oldest grass trees have been lost to land clearing, illegal collection, and changes to fire regimes. It’s vital we care for those remaining. Grass trees are particularly sensitive to Phytophthora cinnamomi, a widespread plant pathogen that is difficult to detect and control, and kills plants by restricting movement of water and nutrients through the vascular tissue.

Growing native plants can be a wonderful way to contribute to the conservation of genetic diversity, and attract native fauna into your garden. Grass trees certainly make an interesting conversation plant!

Read more:

It’s hard to spread the idiot fruit

They can easily be grown at home, provided they’re sourced from a reputable supplier. The best way is to grow from seed, but patience is required as growth can be slow. Despite being relatively hardy, grass trees do not like being moved once large or established, so translocation of plants is not advised. In my opinion, the best way to see grass trees in their true splendour is to visit them in their natural habitat.![]()

John Patykowski, Plant ecologist, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.