Two years ago, researchers from the University of Wollongong in Australia shook the science world by claiming to have discovered 3.7 billion-year-old fossils in a rock formation in Greenland, a finding that pushed back the origin of life on Earth by 200 million years. New research is now casting doubt on this discovery, with scientists saying the rock structures are of non-biological origin.

In the original 2016 study, geologist Allen Nutman and colleagues identified cone-like structures, ranging between 1 and 4 centimeters in length, in 3.7-billion-year-old rock found in the Isua formation in southwest Greenland. These structures, the researchers said, were evidence of stromatolites—sedimentary formations created by the layered growth of microbial organisms in shallow waters. At the time, it was considered the oldest evidence of life on Earth, demonstrating the rapidity with which life emerged after the formation of our planet some 4 billion years ago. The finding carried profound implications not just for our situation here on Earth, but for other habitable planets in the galaxy.

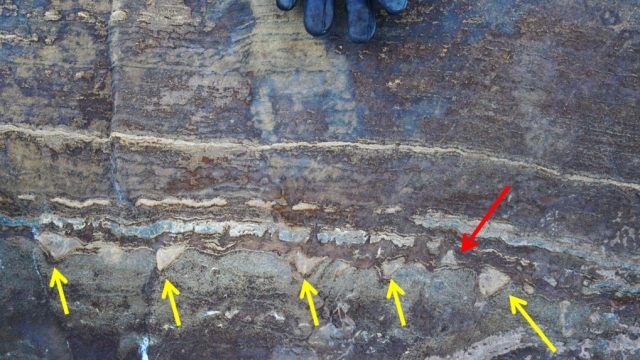

The apparent stromatolites were identified in badly deformed “metamorphic” rocks, which have been heated, twisted, crushed, and contorted over the vastness of geologic time. Despite this, Nutman’s team said they were able to see the signs of sedimentary history within the rocks, including the alleged stromatolites. No organic compounds or biomarkers (so-called “chemical fossils”) were found, but the conical-shaped structures and finely layered textures were interpreted as the remnants of ancient microbial life. At the same time, Nutman ruled out other possibilities, such as weirdly folded rock.

Sceptical of these conclusions, Abigail C. Allwood, a geologist from the California Institute of Technology, Minik T. Rosing, a geochemist at the University of Copenhagen, and colleagues decided to visit the Isua formation in Greenland and take a look at these rocks for themselves. Their resulting analysis, published today in Nature, suggests Nutman and his colleagues got it wrong. The observed structures in the rocks are just products of tectonic processes, they say, and there’s absolutely nothing biological about them.

Nutman, despite these claims, is standing by his work, saying Allwood and Rosing have failed to discredit his team’s analysis. Meanwhile, another researcher not involved in either study is claiming that both teams have insufficiently proven their points, and that the search for the planet’s oldest microbial fossils continues.

For the new research, Allwood and Rosing analysed the three-dimensional shapes, positions, and chemical composition of the rocks purported to contain the fossils. The formations in the Isua rocks are devoid of internal layers consistent with microbial life, they say, and they do not contain any organics or chemical evidence of biological life.

What’s more, a new 3D perspective of the structures suggests they’re not even conical in shape—they’re actually ridge-shaped, according to the new analysis. Cuts made to the rock “show that the ‘stromatolites’ are not cones or elongate cones, but ridges extending at least 10 cm (our sampling depth) into the rock, aligned with the lengthening direction,” the researchers write in the study. “The ridges probably extend further, given the extreme elongation of the rock fabric observed in the outcrop.”

Accordingly, Allwood and Rosing “propose that none of the previously published results support the interpretation of the [Isua] structures as stromatolites.” The rock formations are non-biological in nature, the researchers say, interpreting the “structures as products of structural deformation and carbonate alteration of layered rock.” But if there’s anything Nutman, Allwood, and Rosing do agree on, it’s that the formations were created in a marine environment.

Gizmodo reached out to Nutman for comment—and he made it clear that he’s unimpressed with the attempted takedown of his team’s research.

Among Nutman’s many complaints is that Allwood and her colleagues spent little time at the Isua formation in Greenland, and that they made fundamental errors during the brief time they were there. He said that a “Greenland government observer” who attended Allwood’s expedition said it was a “short one-day helicopter trip,” and that the scientists avoided the site (outcrop B) explored by Nutman because it was “covered by a thin layer of snow,” choosing a different, more accessible site (outcrop A) instead. “Unlike us, they did not examine extensively the relationships with the geology of the surrounding outcrops,” he told Gizmodo. Nutman said he’s “mystified” that Allwood and her colleagues focused on the far end of the site A outcrop, which his team avoided because of the severe tectonic deformations and chemical weathering observed in this particular part of the rock formation.

“This is a classic comparing apples and oranges scenario, leading to the inevitable outcome that ours and their observations do not exactly match,” Nutman told Gizmodo. “Allwood never took up the offer made by our team to lend our samples to them, so they could make an independent assessment of the best-preserved original specimens.”

Nutman argued that because of their short time in the field, and without having viewed all the outcrops, Allwood and Rosing were at a disadvantage and unable to perform an adequate examination. As an example, he said his alleged stromatolites were only seen at the center of rock folds, where smaller degrees of deformations allow for the preservation of “primary structures” within the rocks.

As for Allwood et al’s claim that tectonic compression produced the structures, Nutman said this interpretation “completely fails to explain” why the bottom of the observed stromatolite structures are flat and only the tops are irregular. “This is not how layered rocks like those at the stromatolite locality behave in tectonic compression,” he said. Allwood’s team claims the rock structures aren’t internally layered, “but this is not true,” said Nutman. “Indeed, the stromatolite structures we showed do contain vestiges of layering.”

Based on these and other issues, Nutman said “we stand by our interpretation that there are extremely rare stromatolites in the Isua rocks, preserved in a tiny relict of a 3.7 billion year old shallow sea environment.”

Dominic Papineau, a geochemist from the University College London who wasn’t involved in either study, wasn’t impressed with the re-analysis or the original paper, saying the “evidence either way remains very thin.”

The Nutman paper introduced the possibility of the rocks containing fossils, but Papineau said Allwood and Rosing failed to perform their own due diligence on the matter.

“There was no systematic analysis of the microscopic fabric, mineral assemblages, and of the possible presence of graphite (from metamorphosed biomass) and its composition in these unusual rocks,” Papineau told Gizmodo. “This new work is not advancing any of these important aspects, which remain critical to assess a possible geobiological origin, but are almost entirely undocumented.”

A big issue that Papineau has with the paper is that Allwood and Rosing failed to perform a comparative analysis of rocks that were either older or younger than the samples studied. If they looked at older rocks, for example, and were able to show consistent geological processes over time (specifically the tectonic process described in the study that supposedly explains the stromatolites), they would’ve had further evidence to strengthen their case, he said.

As for the new 3D view of the structures, which caused the researchers to question the supposed conical shape of the stromatolites, Papineau said this interpretation “lacks support from younger stromatolite-like rocks in similarly deformed” outcrops. Like Nutman, Papineau is questioning both the samples used and not used in the new analysis.

Ultimately, Papineau said the jury is still out on the matter, as he feels Nutman’s paper “was not compelling either.” Part of the problem, he said, has to due with the challenges of identifying microbial life in such ancient, tortured rocks.

“This is difficult because the geology background of each worker is different and hence usually biased by this range of experiences,” Papineau told Gizmodo. “The biggest challenge remains the ability to generate compelling data sets with multiple independent techniques, each with their own limitations and data representation, to obtain multiple independent lines of evidence.”

Papineau himself is very much invested in this line of research. In March 2017, he published evidence showing potential signs of microbial life in 3.7 billion-year-old Canadian rock.

This isn’t the only fossil debate underway at the moment. Scientists are also in disagreement about whether another ancient fossil, the 558-million-year-old Dickinsonia, is an animal, plant, fungus, or something else entirely.

[Nature]