You wear it once and throw it away. At least that was the idea.

During the 1950s and 60s an idea emerged that was decidedly sci-fi. The future was supposed to be filled with disposable clothes that could literally just be thrown in a fire after you were done with them. Disposable clothes were supposed to make our lives easier. The only hurdle, according to futurists of the time? The fact that people saw the entire practice as wasteful and bad.

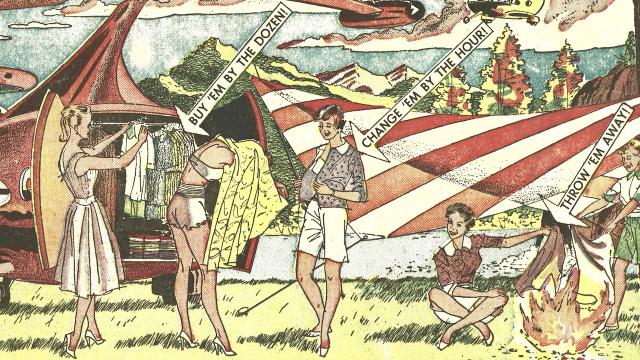

Americans opened the Sunday newspaper on October 25, 1959 to find a comic strip that was selling the idea of disposable clothes. The strip was Closer Than We Think, which was syndicated in roughly 200 newspapers around the U.S. at its peak. Illustrated by Detroit-based commercial artist Arthur Radebaugh, the colourful strip showed women on a camping trip who had bought their clothes “by the dozen” and were changing them “by the hour.”

Do your clothes need to be cleaned or washed? Are you tired of the old patterns or colours? In the future, if your answer to any of these questions is yes, you’ll simply throw the old clothes away—and maybe kindle a camp fire with them.

Yep. Just chuck those old clothes in the camp fire when you’re done. The strip went on to explain that clothes of the future would be made out of paper, presumably more durable than the 8.5 x 11 sheet that you can pull out of the printer tray:

Much of tomorrow’s wearing apparel may be made out of treated paper, intended for use a few times, then for discard. The Quartermaster Corps is already investigating the use of such processed paper for parachutes, disposable uniforms, pup tents, and other shelters. It wears well, and its insulating qualities make it usable in all kinds of weather.

One aspect of the comic strip you may not have even noticed? They’re flying in their own commuter aeroplane. Yes, the flying car of tomorrow would even be with you on those camping trips. And they were doing it in style all thanks to the throw-away clothes of tomorrow.

The emphasis on disposable clothes at midcentury was a collision of two cultures in some ways. The first was a technology culture rooted in space age tech lifted by advances that had been made by engineering new kinds of materials more inexpensively. The paper dresses of the 1960s were created with fibres like rayon, a kind of artificial silk which has its roots in the 19th century, but which could be mass produced at less expense by the 1960s. Or they were created using DuPont’s Reemay, sold as a “more durable cousin” to the paper dress because it was similar to polyester. The second was a culture of sexual liberation embraced by the baby boomers and put on display through dresses that were getting shorter and shorter.

The disposable clothes of the future weren’t parkas for trekking through the tundra. They were the flower child mini-skirts of a young generation rebelling against the stuffiness of the 1950s.

But the way that all of this was packaged wasn’t necessarily through the lens of beatniks and hippie kids and women’s liberation. There was just as much salesmanship going on to convince the “traditional” American housewife that disposable clothes were for her. And it wasn’t just the Sunday funnies that were promising such things. The regular “news” portion of the newspaper were imagining a very similar future in the early 1960s.

The October 12, 1961 edition of the Evening Capital in Annapolis, Maryland gave readers a preview of what was supposed to be coming around the bend:

A research laboratory cuts its big laundry bill way down by sending dirty smocks, coveralls, etc., to the garbage pail. A housewife convinces her husband that her new party dress is a good bargain because she’ll be able to wear it four times before throwing it away. Vacationers, ready to head home, stuff campsite trash and bedding into pillowcases and throw them into the campfire.

Disposable clothes are here – still being tested, but very much alive and kicking.

The article said that consumers just need to be sold better on the idea of disposable clothes—and get over their hangups about creating more waste.

Part of the problem is one of salesmanship. Disposable clothes are still a novelty and command novelty prices. In addition, the American public is still hamstrung by the idea that waste is bad.

Ads for paper dresses of the 1960s commonly boasted that they could be worn “as many as six times,” and were sold from between $US1 ($1) and $US20 ($28) depending on the fibre, or roughly $US8 ($11) to as much as $US170 ($241) adjusted for inflation.

As Virginia Knight explains in here 2014 paper, “The Answer to Laundry in Outer Space: The Rise and Fall of the Paper Dress in 1960s American Fashion,” the Scott Paper Company, more famous for its toilet paper and tissues, started a promotion in 1966 to get in on the disposable clothes fad. Scott’s dresses were made using something called “Dura-Weave,” which was marketed as better than simple paper because it was fire-proof.

According to Knight, their paper dress campaign was little more than an advertising gimmick, but it struck a real chord in the country and some business executives were convinced that it really was the wave of the future.

“Five years from now 75% of the nation will be wearing disposable clothing,” Ronald Bard, VP of Mars Manufacturing Company, said in 1966 according to Knight’s research. Why was he so confident? His company had sold over 300,000 pieces of paper clothing in the second half of 1966 alone.

And the fad was international. A syndicated column in the May 26, 1966 edition of the New York Daily News included word from Paris that disposable clothes were the hottest thing around.

What is the fabric of the future? “Paper” is the answer of dynamic young Paris read-to-wear designer Daniel Hechter. Everyone thought he was joking until his first cellophone-paper wardrobe appeared last week. With it Pasisiennes are jostling to buy these transparent mini-skirted shifts in 10 crystal-clear colours, ranging from amber to hot pink, and from silver to peat grey. All of them swing on shoulder straps or halter neckbands edged in bright shiny colours by day, or piped in silver or gold by night.

Based on my own search of newspaper articles, the “disposable dress” peaked sometime in 1967 or 1968, but the idea of disposable clothes didn’t die in the 1960s. People of the 1970s still entertained the idea, even if they had no experience with actually trying out the concept.

A British clothing industry report from 1970 about the future explained that while people seemed to be curious about the subject, there were plenty of reservations:

Disposable clothes are seen by consumers as a completely different concept from normal clothing. All of those interviewed appeared aware of the development of disposable cloths. None had any first hand experience of wearing them.

They were invariably associated with paper, and this raised strong anxieties about tearing and about what happened if they got wet.

And there was even a conference held in England in 1970 called the Dispo ‘70. That’s right, the Dispo(sable) clothes conference.

Yes, disposable clothes were impractical for a number of reasons including their inability to stand up in tough weather and even their lack of durability through normal wear. And all of that is to say nothing of the sheer wastefulness of the entire idea, something that futurists of the 1960s saw as impractical, but would become much more top of mind for Americans of the 1970s who were living through an energy crisis and the collapse of the environment through industrial pollution.

The idea of disposable clothes see a mild resurgence every once in a while, but the people of the 21st century already live in a world of disposable clothes without that being the explicit promise of what they’re buying. Americans have grown used to buying cheap clothes thanks to the overseas labour of exploited textile workers. And it’s easy to forget about the human cost of that $US5 ($7) t-shirt from Target or H&M. As recently as 2013, a 9-story building collapsed in Bangladesh killing over 500 workers who were creating clothes for the West.

Disposable clothes, even if we don’t call it that, have a very real human cost. Unfortunately, we have to choose between cheap clothes and human lives. And in an environment where our politicians won’t stand up for human rights around the globe, that pressure falls squarely on us as consumers.