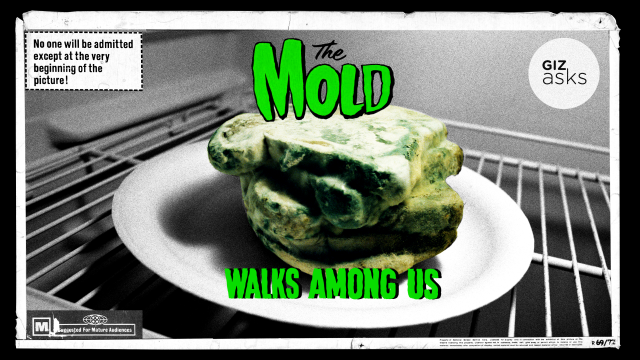

Pretty much everyone can agree that mould looks disgusting, or worse than disgusting. It lays claim to hummus tubs and shower curtains with what feels like intent—it looks alive, possibly because it is. But does this colonising fungus, beyond its surface-level repellence, actually mean us harm? If you just bit into the refrigerated remains of a sandwich, and came away with a mouthful of mould, should you head to the ER or just vigorously brush your teeth? With instances of mould-linked deaths reported recently at Seattle’s Children Hospital, it’s apparent that how, when, and what kind of mould you encounter (and who you are) matters. For this week’s Giz Asks, we reached out to a number of experts for clarity.

Ronald E. Gots

Principal, International Centre for Toxicology and Medicine (ICTM)

Is mould dangerous? A far too simplistic question. It’s like asking: are aeroplanes dangerous? Is bacteria dangerous? Trillions of bacteria live in our intestines and they are essential for our normal function, but if they get into the blood stream, they can be fatal. Moulds account for almost 25% of the world’s biomass. They are essential for breaking down plants and trees, returning their vital constituents to the soil. We live in a virtual aerosol of moulds which are all around us all of the time. For the most part they are benign. For those who are allergic, they may produce allergy symptoms, no different from dog and cat dander. On occasion they may cause infections which can be quite serious. Histoplasmosis and coccidiomycosis, which occur from outdoor moulds in the Ohio and California areas respectively, infect about 1000 individuals per year and cause moderately severe respiratory infections. So, in response to the question: On rare occasions certain moulds can produce illness. Overwhelmingly our experience with moulds is mostly beneficial and rarely harmful.

Robert L. Buchanan

Director, Centre for Food Safety and Security Systems, University of Maryland

Most moulds aren’t dangerous, just as every snake isn’t poisonous. But some are.

The kinds of moulds that develop in food—the kinds that make your food look green and fuzzy, or white and fuzzy, etc.—are common in products that are a little bit too moist and and left at room temperature, or left too long in the fridge. These moulds might affect taste, and don’t look very appetizing, but most of them aren’t particularly important. I wouldn’t recommend eating them, but if you had a bit by accident it wouldn’t be a problem.

However, there are moulds associated with foods that really can be quite dangerous. These are moulds that produce a variety of different toxins known collectively as mycotoxins. Probably the most important of these, in terms of public health around the world, is a group of toxins known as aflatoxins. These are quite potent hepatic toxins—liver toxins—and they’re also the most carcinogenic biological agent produced by another biological entity. They’re typically associated with dry products that have been stored with a little too much moisture, and they tend to like warm environments, though they will grow on even a slightly warm day. Corn and peanuts are two of the classic foods that wind up being contaminated like this. There are a lot of requirements and controls put on these kinds of commodities to make sure they’re stored properly and that contaminated products do not enter into the marketplace.

Theoretically, you could take enough of an aflatoxin to kill you within 24 hours. But in reality, to directly damage your liver would require consuming about a milligram a day over the course of a month. This is typically seen in developing countries.

This is the worst of them, but there are literally hundreds of other toxic compounds produced by a small percentage of the moulds. Conversely, some moulds are actually used in food production—if you take a little bit of the blue part out of blue cheese and put it under a microscope, you’ll actually see the mould growing, and traditional soy sauce is fermented with a mould in order to get the proteins within the soybeans to break down. A lot of it depends on what the mould is growing on.

Nancy Keller

Professor, Bacteriology and Medical Microbiology and Immunology, University of Wisconsin-Madison

It depends which fungus you’re talking about. Mould is a common name of certain type of filamentous fungi; most people, when they use the word mould, are probably referring to fungi that they see growing on their shower curtains or on food in their refrigerator. But that’s only a tiny representation.

Some fungi produce toxins called mycotoxins in our food substrates, and one of them, for example aflatoxin, is very well-known. It is a liver carcinogen—in fact the most potent natural liver carcinogen known to humankind—and, especially in those countries where governments does not have enough money to monitor the food supply, it can lead to liver cancer.

Aflatoxin invades seed crops like peanuts or corn seed or tree-nuts. Harsh climate conditions—especially heat—can result in high production of it: there are some studies suggesting that climate change will lead to higher aflatoxin production in seed crops.

But there’s a yin-yang here. Aflatoxin is a natural product of fungi that we don’t like, but penicillin is a natural product of fungi that we do like. The accidental discovery, in 1928, of penicillin was utilised to a fantastic degree to keep our troops alive during World War II, and there are many beneficial natural products that come from mould fungi that have been very helpful in fighting disease. So it really depends on the context: where the mould is growing and what the product of the mould is.

Seri Robinson

Associate Professor, Anatomy of Renewable Materials, Oregon State University

Most moulds are not dangerous, in any way. Many people mistake allergic reactions to some type of toxic response. If you dig into the scientific literature you’ll find that the jury is still out even on ‘black mould’ being an issue, with some studies saying it has no effect, and others describing the end of the world.

Fungi are a kingdom. To say moulds are dangerous (when people use the word mould to mean fungi), is like saying because some species of spiders are venomous, we should avoid all dogs. Same kingdom… very different creatures.

Ginger L. Chew

Deputy Associate Director for Science in the Division of Environmental Health Science & Practice (DEHSP) at the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention

Mould has been associated with several health effects. For some people, mould can cause a stuffy nose, sore throat, coughing or wheezing, burning eyes, or skin rash. People with asthma or who are allergic to mould may have severe reactions to mould exposure. Immune-compromised people and people with chronic lung disease may get infections in their lungs from mould.

Inhalation of mould spores, mycelia, fragments of spores and mycelia, and mouldy odours (i.e., microbial volatile organic compounds, mVOCs) has been associated with irritant effects in humans regardless of underlying susceptibility. In high concentrations such as those in some farming environments, some fungi can lead to hypersensitivity pneumonitis (e.g., farmer’s lung). However, it is difficult to know what a high concentration is, so our recommendation is to control the moisture source and clean up the mould, regardless of type of mould.

We do not use the term “mould poisoning,” but we do know that for people who are sensitive to moulds, exposure can lead to symptoms such as stuffy nose, wheezing, and red or itchy eyes, or skin. People with allergies may be more sensitive to moulds. Also, individuals with chronic respiratory disease (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, asthma) may experience difficulty breathing. Severe reactions to mould exposure may include fever and shortness of breath. People with immune suppression or underlying lung disease are more susceptible to fungal infections.

In 2004 the Institute of Medicine (IOM) found there was sufficient evidence to link indoor exposure to mould with upper respiratory tract symptoms, cough, and wheeze in otherwise healthy people; with asthma symptoms in people with asthma; and with hypersensitivity pneumonitis in individuals susceptible to that immune-mediated condition. Other recent studies have suggested a potential link of early mould exposure to development of asthma in some children, particularly among children who may be genetically susceptible to asthma development.