The covid-19 museum closures have made abundantly clear that accession committees and the web’s corporate overlords don’t have much love for net art. While museums spent the past decade and hundreds of millions of dollars colonising the earth and sky to make space for hoards of painting and sculpture, the web’s billboard-plastered renovations have threatened to steamroll it into oblivion. (Nowhere is this more obvious than Google’s Arts & Culture, an online repository for work from 2,000 museums and collections, whose media include “vitreous enamel,” but not “video”–much less “HTML” or “gifs.”)

They’ve put their collections online, but a .png of a Mexican mural stimulates about as much as a postage stamp; we need art that comes alive on browsers, and you’re going to have to do a little off-roading into the diaspora of blogs, strange domains and obscure YouTube channels to find it. While scanning the web for online artworks for socially distanced consumption, Gizmodo wondered: how did net artists find net art? Which works led them to fire up their terminals and Photoshop canvases and build out this fragile universe for the public? For a series of days (however long we can find contributors), we’ll be sharing picks from the community of art-makers and caretakers who’ve created and preserved net art for the world, free of charge.

LoVid and Daniel Temkin pick JODI

When asked for their earliest inspiration, the artist duo LoVid simply answered: “Jodi.org !”

The name of the artist duo JODI (aka jodi.org), founded in 1994, carries about the same weight as Duchamp’s in canonical importance. Using a 20th-century analogue to explain net art is bound to piss somebody off, but the radical spirit of plopping a urinal in a fine art exhibition lives in JODI’s smart repurposing of the internet’s ugly freight that web design takes pains to disguise. While the web was in the business of curtain-making, JODI was smashing windows.

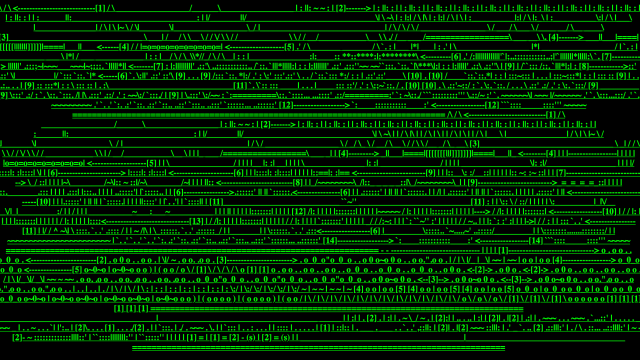

Their eponymous work redirects to chaotic websites that look like they’re going to torpedo your computer; don’t worry, they won’t. “Jodi.org” may take you to Flash videos of Max Payne glitches, a simulated crashed browser, what look like blooper clips of a thumb covering the camera lens. It’s a carefully choreographed, simulated joyride into the internet’s rocky outer terrain.

That impulse to stomp boundaries can be seen in LoVid’s work, specifically their 2003 video “Breaking and Entering.” They take what look like glitches and turn them into collages and then print them on textiles, and perform online spaces as physical bubbles.

Theorist and programming composer Daniel Temkin also pointed to JODI, but their more minimal 2016 project, “IDN” (short for “Internationalized Domain Names”). The artists got around the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority’s decadeslong ban against single-character domain names by registering domains in Punycode, the ASCII translation of Unicode glyphs, which automatically populates as a string of alphabetical characters in your address bar: the result is that you can click on ᠐.com, ꀍ.com, and ꇎ.net and arrive at a website.

The sites present the most rudimentary cogs of the web: a directory of empty files, a directory to nowhere, pages that appear to generate strings of their own glyphs. In his expansive research series “Esoteric.Codes,” Temkin observes of ꀍ.com that the site doesn’t rely on fancy animation and third-party programs, but is pure code; it redirects from domain to domain, each showing a string of characters on its homepage, before moving to the next. “It is a movie, with each frame on a different website, and we’re forwarded from one to the next,” he writes. “It very consciously eschews complexity or web styling; apart from the availability of Unicode-friendly fonts, nothing in IDN would work differently on a browser from the early web.”

JODI are not the only net artists mining raw materials, and Temkin also suggested taking a look at Evan Roth’s “All Html,” a single page with every HTML tag wrapped around one other in alphabetical order, “tweaked just enough to avoid collapsing into the defeat of a blank page.” There’s also “Portrait of a Web Server,” Jan Robert Leegte’s Apache server that reveals its source code on any browser that pings it. “The code is served to us using the performance of itself as its delivery mechanism,” Temkin writes.

Temkin sold himself short by failing to mention his own work, which he often describes as “collaborations” with programs and machines. “Dither Studies” (a “collaboration with Photoshop”) refers to the algorithmic process of “dithering”: a typically invisible process in which a computer graphics program selects from available blocks of colour and groups them together in order to create the illusion of depth and colour spectrum. (Here’s a black-and-white example of Michelangelo’s “David.”) Temkin dithered solid colour blocks or gradients of complementary colours that will never seamlessly mesh. The rules of an algorithm look like a machine’s revolt.