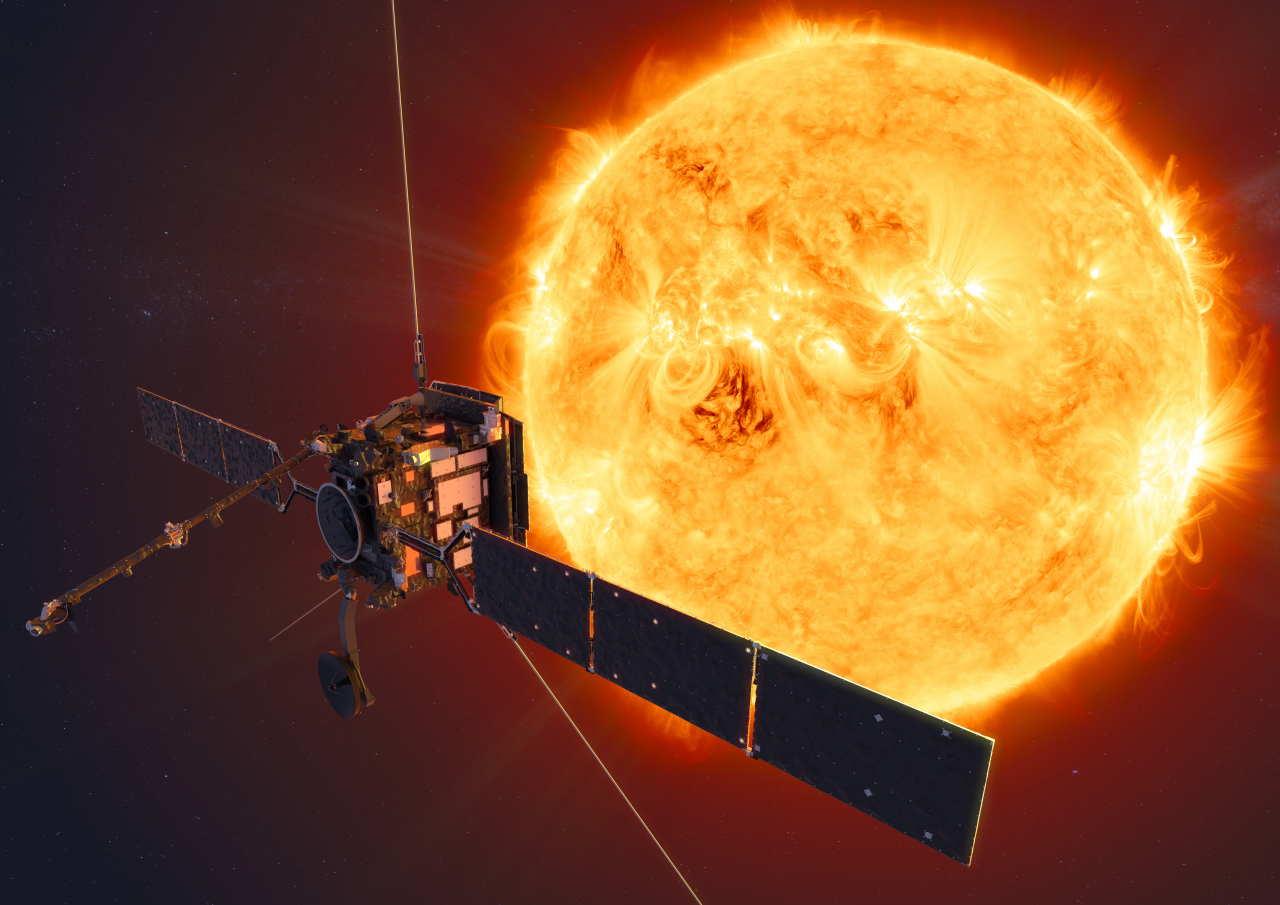

The Solar Orbiter project, a collaboration between the European Space Agency and NASA, has begun a critical new stage of the mission after the probe’s first close encounter with the Sun.

Earlier today, the Solar Orbiter completed its first close approach of the Sun, or perihelion, coming to within 77 million kilometres of our host star. It’s a significant milestone for the mission, as the probe, launched in February, has transitioned from the commissioning phase to the cruise phase. Mission controllers will now test its many onboard instruments over the next five months, after which time the Solar Orbiter will officially begin the science phase of the mission.

Developed by the ESA with help from NASA, the probe features 10 distinct onboard instruments, many of which complement each other. Equipped with six different cameras, the probe will provide unprecedented close-up views of the Sun. A primary goal of the mission is to better understand the Sun and how it creates and controls the dynamic environment within our solar system.

“We have never taken pictures of the Sun from a closer distance than this,” said Daniel Müller, an ESA Solar Orbiter project scientist, in a press release. “There have been higher resolution close-ups, e.g. taken by the four-metre Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope in Hawaii earlier this year. But from Earth, with the atmosphere between the telescope and the Sun, you can only see a small part of the solar spectrum that you can see from space.”

This mission is not to be confused with NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, which launched in 2018. The Parker probe is currently swirling down the celestial drain as it gets increasingly closer to the Sun, where it will eventually meet its doom ” a sacrifice that will yield important information about the Sun’s corona, or outer atmosphere.

Unlike the Solar Orbiter, however, Parker doesn’t have any cameras. A better comparison would be NASA’s Solar Dynamic Observatory (SDO), which takes high-resolution images of the Sun but at distances approaching 1 AU, which is the average distance between Earth and the Sun. The Solar Orbiter is much closer, currently at 0.515 AU from the Sun.

“This is the first time that our in-situ [onboard] instruments operate at such a close distance from the Sun, providing us with a unique insight into the structure and composition of the solar wind,” said Yannis Zouganelis, the deputy project scientist for the mission. “For the in-situ instruments, this is not just a test, we are expecting new and exciting results.”

Mission controllers will now put the Solar Orbiter’s tools through their paces, collecting preliminary data about the Sun’s corona, surface, heliosphere, magnetic field, and particles within the solar wind. The first images collected by the Solar Orbiter ” which are expected to be at twice the resolution of SDO images ” won’t be released until July.

Eventually, the Solar Orbiter will get to within 42 million km of the Sun, or 0.28 AU, which is slightly closer than Mercury’s perihelion of 0.31 AU. The Parker Solar Probe, by comparison, will come to within 6.1 million km, or 0.04 AU of the Sun, but its mission goals are different.

Eventually, a series of gravity assists from Earth and Venus will nudge the Solar Orbiter out of its current position along the planetary ecliptic plane by a factor of 24 degrees. At this higher orbital altitude, the probe will scan the Sun’s poles and provide us with views of these elusive solar regions, which influence the Sun’s magnetic field and solar winds.

It’s an exciting time to study the Sun! Insights from both the Parker Solar Probe and the Solar Orbiter should dramatically improve our understanding of space weather and possibly enhance our ability to predict potentially dangerous solar flares.