The catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius nearly 2,000 years ago is famous for preserving its many victims in volcanic ash. New research suggests this preservation extends to the cellular level, owing to the apparent discovery of neurons in a victim whose brain was turned to glass during the eruption.

New research published today in PLOS One describes the discovery of neuronal tissue in vitrified brain and spinal cord remains belonging to a victim of the Mount Vesuvius eruption, which blew its stack in 79 CE.

“The discovery of brain tissue in ancient human remains is an unusual event,” Pier Paolo Petrone, a forensic anthropologist at University Federico II in Italy and the lead author of the new study, said in a press release. “But what is extremely rare is the integral preservation of neuronal structures of a 2,000-year-old central nervous system, in our case at an unprecedented resolution.”

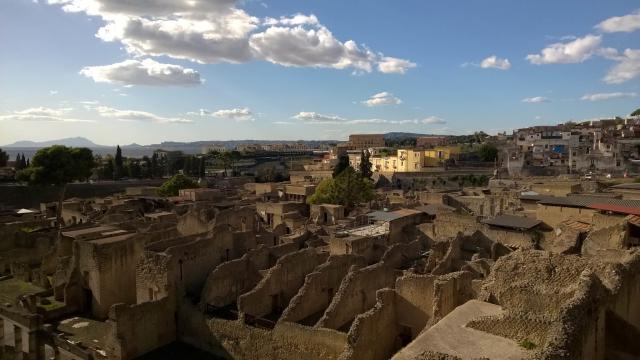

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius devastated several ancient Roman cities, including Herculaneum, Pompeii, Stabiae, and Oplontis. Following a series of earthquakes, the volcano tossed a massive column of molten rock, hot ash, and pumice into the sky. Inhabitants of nearby settlements quickly succumbed to pyroclastic flows — fast-moving avalanches of superheated material. An estimated 2,000 people were killed during the eruption.

The falling volcanic ash resulted in rapid burials and the preservation of many victims, including the famous preservations at Pompeii. In some cases, however, the intense heat caused victims’ skulls to explode, as temperatures suddenly spiked to 932 degrees Fahrenheit (500 degrees Celsius). In Herculaneum, some inhabitants sought shelter in nearby boat chambers, where they were baked alive.

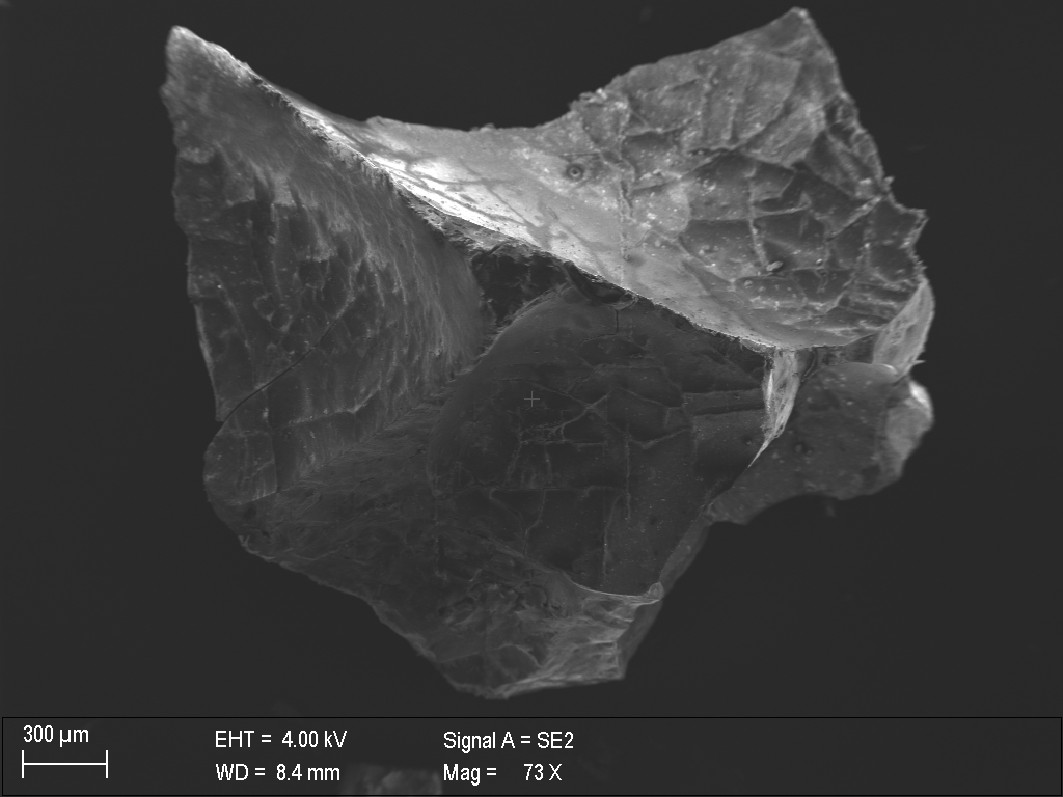

Research published earlier this year in the New England Journal of Medicine showed that the extreme conditions on that fateful day also turned one victim’s brain into glass, described in a paper led by Petrone. Vitrification is the process in which intense heat turns tissue into a glassy substance — a reasonably good medium for preserving structure at both the macro and micro scale. The male victim, found in Herculaneum, was found lying on a wooden bed and buried in volcanic ash.

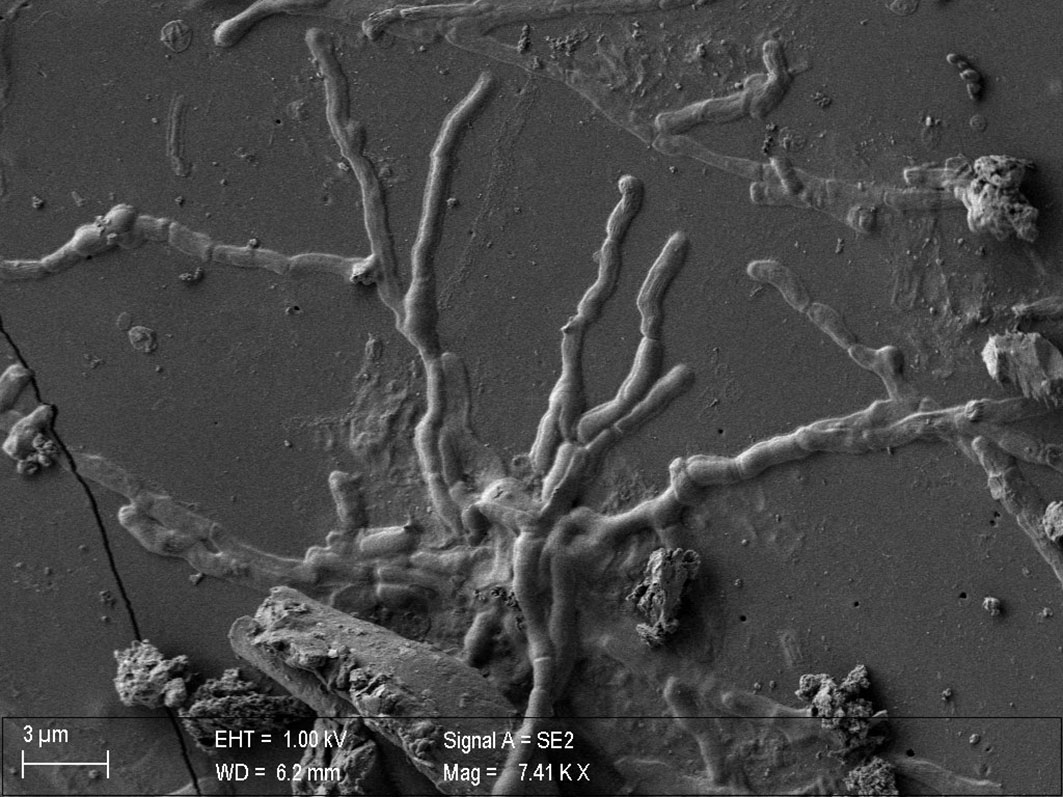

Petrone, along with an interdisciplinary team of experts, have taken a deeper look at this same vitrified brain, finding evidence of neuronal structures within. The researchers say this is evidence of the rapid cooling of a hot volcanic ash cloud that struck Herculaneum during the opening stages of the eruption. The resulting vitrification solidified the man’s neuronal structures, keeping them preserved and in place for nearly 2,000 years, according to the scientists.

Using a scanning electron microscope and an image-processing tool designed for neural networks, the team uncovered traces of a central nervous system, including the remnants of brain cells, axons, myelin, and cellular microtubules. The structures seen in these microscopic images look highly organised, suggesting a remarkable degree of preservation in this vitrified brain.

For a second line of evidence, the researchers analysed the proteins they discovered earlier this year, finding that genes within these proteins are associated with the expression of various structures in the human brain. These proteins “further agree with the neuronal origin of the unusual archaeological find,” wrote the authors in their study.

Zachary Throckmorton, a paleoanthropologist and research fellow at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, appreciated the authors’ use of two different lines of evidence to support their discovery, but he’s not entirely persuaded by the new paper.

“Their protein residue analysis supports their claim, but the complexity of how gene expression varies throughout body tissues makes their findings suggestive but not definitive,” Throckmorton said in an email.

On the other hand, the microscopic images shown in the paper “more strongly suggest they did in fact find [nerve cells] preserved in this Vesuvius victim,” he said. Still, Throckmorton believes the authors’ claims could’ve been bolstered by comparative experimental images. To be totally convinced, he’d “like to see their images compared to mammalian central nervous system tissue experimentally vitrified under known, controlled conditions.”

Tim Thompson, a professor of applied biological anthropology at Teesside University in the UK, felt that the new paper, like some of Petrone’s previous work, didn’t contain enough information for “an external person to make a proper assessment of it,” he said during a video call.

Brains, he said, tend to not preserve very well, and they’re often the first thing to decompose following death. Thus, the new study “highlights the complexity of preservation at Herculaneum.” Thompson said he doesn’t know if the authors have truly found preserved neurological structures, but the new paper does show that not all people struck by the wave of superheated gas, known as hot surge clouds, were instantly vaporised. As a forensics expert, Thomas would like to know how a preservation like this is even possible, saying the new paper “really doesn’t address that.”

During the same video call, Matthew Collins, a professor of palaeoproteomics (the study of ancient proteins) at the University of Copenhagen, agreed with Thompson, saying he found it “frustrating” that the authors didn’t release all of their raw data, claiming that Petrone makes a habit of this. The microscopic images shown in the paper appear to “have structures,” he said, “but I would like to see more.” To which he added: “There’s clearly something going on in brain preservation, and that’s super exciting.” That a preservation such as this is possible makes sense, he said, as the human body is a “liquid-rich medium” in which the bits on the outside don’t cook as fast as the parts on the inside.

The opening sentence of the new paper states that the detection of microscopic brain tissue “in human archaeological remains is a rare event that can offer unique insights into the structure of the ancient central nervous system.” Thompson, Collins, and Alexandra Morton-Hayward, a University College London archaeologist who also participated in the video chat, respectfully disagree. A recent NEJM paper co-authored by the trio argues that brain tissue is very common in the archaeological record. In their paper, the scientists provide a wide number of examples, including organic material found in well-preserved ancient Egyptian mummified corpses and skulls found buried in soggy mud pits.

“Your readers need to be aware that, when it comes to finding ancient brain tissue, this latest discovery isn’t so special,” said Morton-Hayward, who led the NEJM study. “Over 1,300 brains have been reported across various contexts in archaeological records since the mid-17th century. It’s staggering at this point, and not unique, and not even exciting in some ways.” The problem, she said, is that these brains aren’t being sufficiently studied, which may explain the underreporting.

To be clear, Morton-Hayward was excited by the potential discovery of brain tissue in the vitrified remains. Preserved brains found in heat-based contexts are “not so common,” she noted, but it does happen, adding that she “wouldn’t be surprised” if Petrone and his colleagues did in fact find “well-preserved microstructure” in the sample.

“Herculaneum is an exceptional site, and with an exciting context,” said Morton-Hayward. “We are finding preserved brains all over the world, and I’m hoping this is the start of a lot more work in that area.”