Last week — in what might somehow qualify as good news for 2020 — bug scientists in Washington State reported discovering and then destroying the first known Asian giant hornet nest in the U.S. These invasive predators pose a serious threat to bees, and researchers are desperate to stop their spread within North America.

[referenced id=”1522752″ url=”https://gizmodo.com.au/2020/10/just-in-time-for-slaughter-phase-scientists-find-first-murder-hornet-nest-in-the-u-s/” thumb=”https://gizmodo.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/24/tc09t0y4pzm62g7ndk9h-300×169.jpg” title=”Just in Time for ‘Slaughter Phase,’ Scientists Find First Murder Hornet Nest in the U.S.” excerpt=”Entomologists in Washington have confirmed the existence of a nest of Asian giant hornets, more fondly known as murder hornets. The nest is the first such breeding ground discovered in the United States, confirming fears that the invasive species could become established and severely threaten the country’s fragile bee population,…”]

Soon after I wrote about last week’s nest discovery, readers buzzed into my inbox with their own tales of having seen murder hornets in their backyard. These supposed sightings, apparently everywhere from Texas to Ohio to New York, would be extremely worrying if genuine, since scientists are worried the Asian giant hornet could threaten the country’s already fragile farmed honey bee population if it became established. So I reached out to entomologists in every state where someone claimed to have seen these bugs to ask what a person should do if they suspect they’re face to face with an Asian giant hornet.

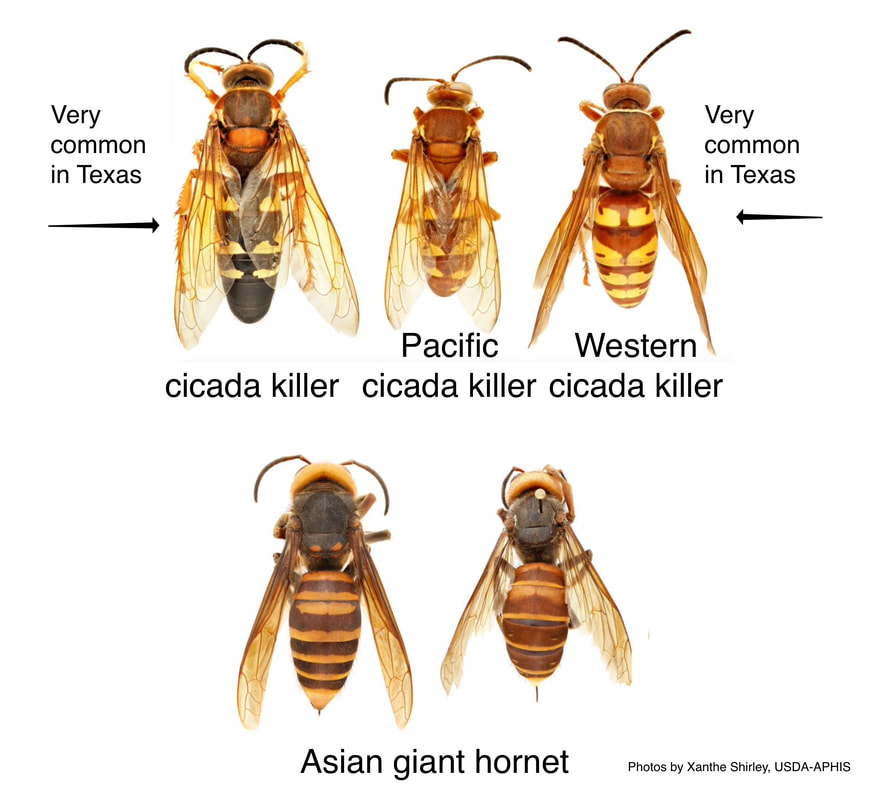

Across the board, the experts told me that all of the supposed sightings I’d received emails about were likely or very clearly cases of mistaken identity. I showed one of the photos, from a reader in Texas, to David Ragsdale, an entomologist at Texas A&M University and chief scientific officer of Texas A&M AgriLife Research, a research agency jointly run by the state and the university. Though the bug in the picture was similar in colour and size to the giant murder hornet — which can get over 2 inches long — the distinctive black markings on its thorax give it away even to the untrained eye. It’s actually the Eastern cicada killer (also just called the cicada killer), a native and usually solitary species of wasp that isn’t quite as big as the largest queen murder hornets can be.

“We’ve had hundreds of photos sent in by people in Texas,” said Ragsdale. Almost inevitably, the pictures turn out to be the Eastern cicada killer or its close relative, the Western cicada killer. Once or twice, they’ve even received photoshopped or misrepresented pictures of the hornet from outside of the U.S. So far, none of these claims have turned out to show that the Asian giant hornet has invaded Texas.

The same seems to be true for North Carolina and other areas of the Eastern U.S.

“Since May 6, I’ve had 306 requests for identifications of a possible hornet,” said Matthew Bertone, the director of the Plant Disease and Insect Clinic at North Carolina State University and an entomologist specifically called upon to identify mystery bugs by the university and state. “I can’t say what’s going on out in the West. But here on the East Coast, and especially here, the European Hornet is by far the most common one that’s submitted. And that’s logical, because it’s a very close relative.”

As to why people are regularly mistaking other insects or creepy crawlies for the hornet, the answer’s pretty simple.

For one, most people can barely distinguish a cockroach from a bedbug. If it’s hard to tell apart common household pests, imagine trying to gauge the identity of a large and terrifying flying insect.

“The biggest thing people latch on to is the size. So it’s not just European hornets. We’re also getting other large wasps and even large flies submitted,” Bertone noted. “So if I could stress one thing, it would be that you can’t just go based on size, because even though you may not have noticed, there are some hefty insects flying around.”

The other reason is more psychological. Murder hornets are a fearsome-sounding creature, and they’re new. That mix of fascination and fright is the perfect recipe for priming you into thinking that you’ve come across the hornets when you really haven’t. I completely sympathise, having had my own bouts of bug paranoia after writing this article on cockroaches and bedbugs.

That said, the invasion of the Asian giant hornet is a real concern. The current leading theory is that they made it to Washington State by hitching a ride on shipping containers from the Pacific. That’s a scenario that could repeat itself elsewhere. Interestingly enough, Ragsdale noted, the Washington nest was found in a tree, an unusual choice for the normally subterranean-dwelling, colony-living hornet. That could be a sign that they’re already adapting to North America in unexpected ways.

“I mean, that’s the thing about invasive insects. You may think that they behave one way because you’re observing them in their native habitat. When you put them in a novel environment, they may behave differently,” he said.

So, whether you’re in a confirmed murder hornet area or not, here’s what to do if you suspect you’ve seen one. For starters, there are webpages and videos created by Texas A&M and others that are dedicated to helping you figure out the difference between murder hornets and other insects. Many entomology departments at universities as well as agriculture departments around the country also have people like Bertone who can identify the mystery bugs for you, so long as you can provide them a fairly recognisable picture or sample. If you can avoid it, try not to squish or harm the suspected bug — chances are, you’re just murdering a valuable member of the community that means you no harm.

“Unfortunately, about two-thirds of the time, what we get is photos of squished insects or insects in a bucket of gasoline or something else. And that’s something that drives entomologists nuts, because they aren’t going to bother you. And they’re usually doing a pretty good service for you,” Ragsdale said. “But there’s not too many entomologists out there. Most people are not bug lovers.”

Sometimes reports from the public really do pay off. The first genuine sighting of the murder hornet in Washington was indeed made by a homeowner in the area, and citizen scientists will remain an essential part of hornet surveillance in areas where it’s known to have invaded. But in areas where the hornet hasn’t been confirmed — which, right now, is every state besides Washington — just know that the chances you’ve truly seen one are low.

“It’s a double-edged sword, because we do want people to be on the lookout, just in case, because if we can catch things early, that’s great,” Bertone said. “But I get a little frustrated when people are adamant that it’s been in the state for years and years and years. With something that’s so large and would be so common, if it was there, we would know and we would let people know — we’re not going to keep it a secret.”