Kotelny Island sits high up in the Arctic, off the coast of Northern Siberia. It’s cold and barren now, mostly absent of humans. But over 20,000 years ago, this island was home to huge megafauna. Melting permafrost is exposing evidence of this past life, including three large woolly mammoth skeletons discovered there in 2019.

One of those skeletons, named the Pavlov mammoth after the man who found it, appears to have been butchered by ancient hunters. We can imagine them, huddled around an enormous carcass, cutting through tangles of fur and thick skin towards the sinew. We might even hear the grunts of their efforts — it’s no easy task — and see their breath in the bitter cold. What was once a substantial woolly mammoth had fallen.

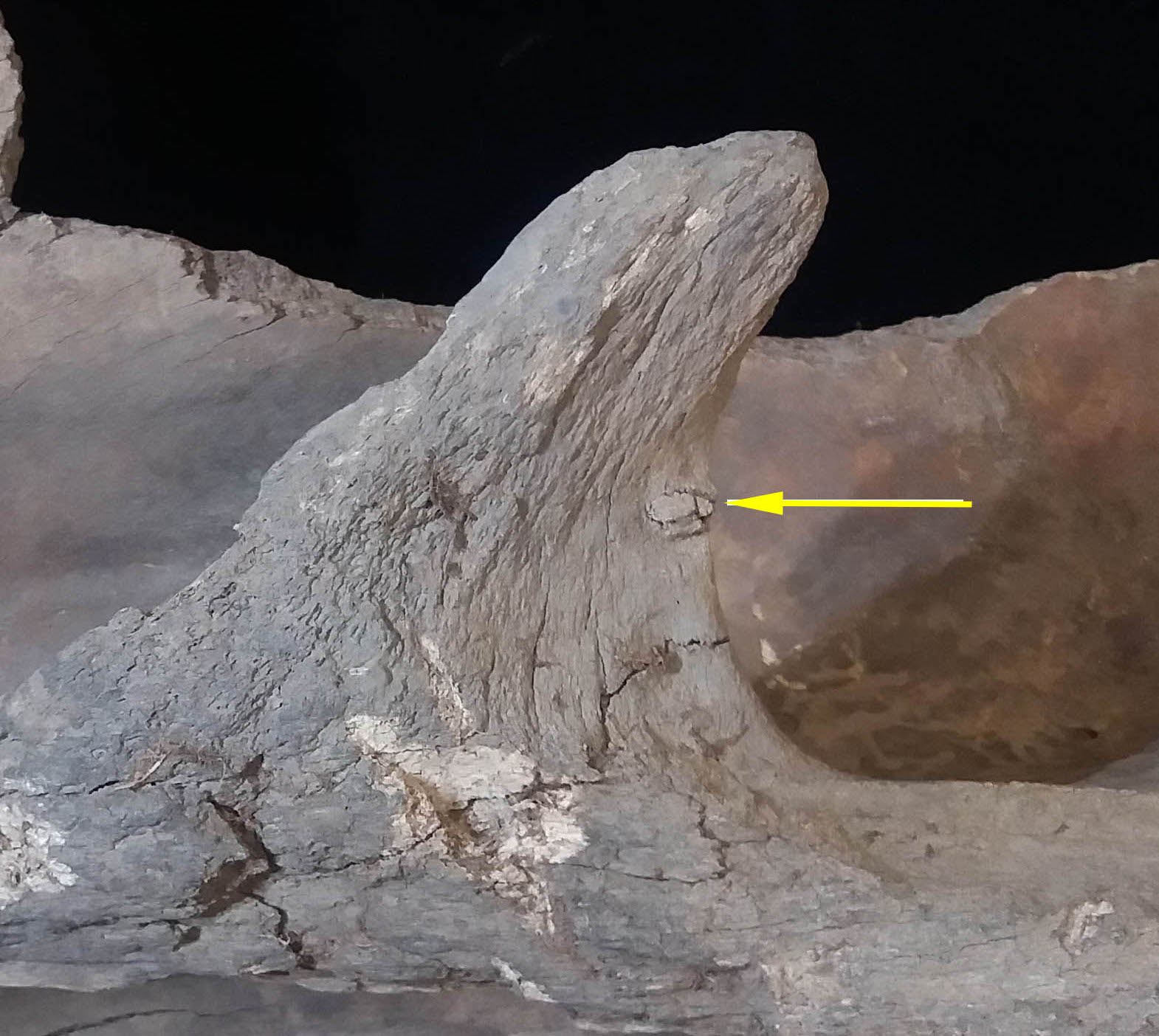

Traces on the mammoth’s bones indicate scavenging from both predators and rodents, numerous breaks, circular cuts along a tusk, and embedded objects within some of the bones, most notably in the shoulder. The intriguing question is: Did humans leave these marks?

Olga Potapova, a paleontologist with The Mammoth Site in South Dakota and an associate researcher with the Pleistocene Park Foundation, Academy of Sciences of Sakha (Yakutia) and Russian Academy of Sciences, presented details of this research during a virtual poster session at the recent annual meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontologists. Paleontologists, paleogeneticists, an archaeologist, and others teamed up to get a better understanding of this particular fossil.

The team made several field trips to the frigid island in recent years, led the project’s scientific advisor Albert Protopropov, head of the Department for Study of Mammoth Fauna, Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). On one of these trips, Innokenty Pavlov discovered the mammoth skeleton and recognised the marks on its bones as possible human hunting marks. Pavlov, according to Potapova, is “a talented field worker, taxidermist and artist/sculptor,” and he led the field work.

This remote island currently supports a Russian military base, the source of transport for the scientists who travel there. Protopopov, in an email translated from Russian to English by Potapova, described the Kotelny Island as “covered by Arctic deserts. Summer lasts only one and a half months, and in summer there is often snow. The usual temperature is 5 degrees C at the end of July (the warmest period). There are no mosquitoes here; it’s very cold for them to live here.” Polar bears and walruses, however, are numerous.

Protopopov described the unintended discovery of the Pavlov mammoth. “Our expedition team went to dig up the carcass of the Golden mammoth [another known mammoth in the area] in the north of Kotelny Island in the spring of May 2019,” he wrote, “but due to the early melting of the snow, the place where the carcass lay was already under the water and could not be excavated. The failure of the expedition was saved due to help of local fishermen, who showed us a place 10 kilometers from the carcass of the Golden Mammoth, where they once saw the bones of a mammoth. A group led by Innokenty Pavlov went there and found dozens of mammoth bones.”

Much of the skeleton was recovered, and all of the bones have marks on them. These marks provide invaluable clues. They do not, however, immediately point to human interaction. Consider natural processes that occur over thousands of years when anything is buried: the shifting of sediments, geological pressure that can cause damage to the bones, not to mention scavenging from other animals and possible trampling by other megafauna at any point in the decaying process. Deciphering these marks has been an important aspect of this research and one that these scientists hope to continue with other experts in the field.

Potapova is no stranger to working with remarkable specimens found in Siberia. Some of them include the Yuka Mammoth, the Yukagir Bison, and the Yukagir Horse, incredibly well-preserved natural mummies from the Pleistocene.

“Unlike other isolated fossil bones found in this particular region and in Northeast Siberia in general,” she explained in an email, “almost every bone of the Pavlov mammoth had tens and hundreds of cut marks and very little indication of [scavenger] gnawing. Many scratches, indeed, will be hard to classify. However, unlike random scratches in many directions caused by sediments and animals’ trampling (and sometimes wear), the large number of long and very thin cuts clustered in parallel fashion are typically recognised by archeologists as being of human origin.”

It’s the location of many of these cut marks that offers insight. Marks around specific bones reflect possible skinning and the removal of fleshy areas that may have been of interest for human consumption.

“For example,” she continued, “the clusters of parallel cut marks around the nasal opening (upper maxillary bones) indicate purposeful de-fleshing in this area. [T]his particular skull area supports the base of the trunk, and it is logical to suggest that these cuts reflected the human activity of separating the meaty and boneless trunk from the head.”

A number of cut marks are also seen along a section of the cranium, suggesting either defleshing of the bone in that area or disarticulating the jawbone from the skull.

The high number of cut marks led Kathryn Krasinski, assistant professor of anthropology at Adelphi University, to question the skills of those particular human hunters.

“When butchering something,” she said in a video chat with Gizmodo, “you actively avoid hitting the bone, because it dulls your tools, so you expect few cut marks on bone.”

She’s not entirely convinced the marks indicate human hunting and is eager to read more once the paper is published. Krasinski and her colleagues studied various ways in which cracks and marks can be made on the bones of proboscideans — a term that encompasses mammoths, elephants, mastodons, and others — using the remains of elephants from Zimbabwe that had died naturally, as well as those that had been culled decades ago. But it’s rare to be able to study post-mortem effects on today’s elephants, as these animals are ecologically threatened. Interpreting marks on proboscidean fossils is highly subjective, making claims about human hunting somewhat controversial.

Although not discovered with a wealth of human artifacts around it, material in and around the bones offer intriguing evidence that there is more to this mammoth than meets the eye. Embedded stone objects remain in the tusk, and an embedded bone object is lodged in the scapula (shoulder), after which the bone healed, which may be the remnants of a weapon made from bone.

“What is most exciting to me about the Pavlov mammoth, yet needs verification, was the apparent lithic embedded in a tusk fragment,” Krasinski said, referring to the embedded stone fragment. “While ivory processing was common in the Paleolithic, it is equally plausible this could have occurred millennia after the mammoth died, as ivory from the far north preserves well. That is to say, the death of the mammoth need not be synchronous with the processing of the faunal remains. We have many examples of this kind of scavenging, particularly across Beringia and into Alaska, where people were picking up fossil ivory hundreds and even thousands of years after the death of the animal. In fact, this still happens today.”

Scientists have yet to find any remains of ancient people on Kotelny Island. This mammoth research provides the first evidence that humans lived that far north.

Chris Widga, paleontologist at the Centre of Excellence in Paleontology at East Tennessee State University and someone who has spent a great deal of his career studying proboscideans, is encouraged by the information provided by the researchers.

“Looking at the authors,” Widga wrote in an email to Gizmodo, “these are people who primarily work on the European and Russian/Siberian record. As such, they are very familiar with the Paleolithic record of mammoth hunting.”

“The modified bone images are fuzzy, but if their descriptions hold out, this is definitely a strong candidate for a human-butchered mammoth,” he said. “There are flakes embedded in bones, chop marks, and circular cuts on the tusk. These are things that we see in other mammoths, as well as elephants that have been butchered in experimental archaeology projects.”

Potapova maintains that the cut marks appear deliberate and that these traces are in very specific locations on the bones and are often parallel to each other. The breaks on the bone, much like the marks, do not suggest the random effects of geological pressures. Rather, they seem strategic.

“According to our study of the Pavlov mammoth skull,” Potapova wrote in an email, “its damage was quite different from these random-broken bones.”

Of particular note, she said, is the example learned from a site in the Russian Plain referred to as the “Yudinovo” site, where evidence of mammoth hunting by humans is well documented. The broken skulls of 32 mammoths suggest humans valued the mammoth brain as food. The Pavlov mammoth skull has similar breakage. Areas where the tusks are connected to the skull are also broken, indicating tusk removal.

The scientists turned to their colleagues at the Centre for Palaeogenetics in Sweden for ancient DNA analysis of the shoulder bone and the bone object embedded within it. They were able to pull almost 8 million reads of mitochondrial DNA from the scapula and a little over that same amount for the embedded object. Those numbers might seem enormous, but Marianne Dehasque, PhD candidate and aspiring paleogeneticist, explained that something like a well-preserved mammoth might offer over 600 million reads.

“What we do here [at the Centre for Palaeogenetics] in Stockholm is we basically [place] all the DNA that we have on a sequencing instrument, and then we look at what appears there. This is called ‘shotgun sequencing.’ You just sequence everything. We also use this approach to generate high-quality genomes,” she said in a video chat. “And in that respect, less than 10 million [reads] is actually not that much.”

But they don’t need much, she explained, to determine basics about the animal. With a little ancient DNA, they can determine the sex. The Pavlov mammoth, they learned, was male.

While the number of mitochondrial DNA reads seemed large, the percentage of endogenous material — DNA that originates from the animal or object in question — seemed shockingly sparse. The poster lists a mere 6% of endogenous material from the scapula; 3% from the embedded object.

“When we try to extract DNA and sequence it, we will see that some part of the DNA will be of the organism of interest, but a large part of the DNA that we retrieve will often be bacterial contamination. But sometimes they’re also caused by people handling it,” Dehasque explained and then laughed. “I’m pretty sure there’s a little bit of my DNA in there, for example.”

Ancient DNA could not prove that the scapula and embedded object were from different individuals, which would offer more conclusive evidence that the embedded object was foreign material introduced into this mammoth. In other words, more proof that this mammoth was hunted.

“There’s a ton of research to do here,” Krasinski noted, “and I’m glad that people are working on questions of bone taphonomy, because if we’re really going to understand mammoth extinction and human interactions with these big creatures, we need to continue studying all of the mammoth collections we can. This poster is an excellent contribution in that direction.”

Widga mirrors that enthusiasm.

“I’m really looking forward to a full report on this mammoth,” he wrote. “This is clearly a detailed, complex, interdisciplinary project with lots of moving parts. A poster just doesn’t do it justice. This is yet another site that is bringing the question of ‘how did people hunt and butcher mammoths?’ into better focus. This question is harder to answer than it would seem — and in the last few years, as we have discovered some really good northern mammoth butchery sites, we have made a lot of progress on the issue.”

If ancient humans did hunt woolly mammoths and other animals on this island, what else can we learn about that ancient ecosystem and those that lived there?

“We view [the Arctic] region as holding clues to the earliest human population in Western Beringia, with direct ties to that of the North American population,” Potapova wrote. “I personally also hope that this find and our research will deepen people’s perception of the Arctic during the Last Glacial Maximum. Due to a drop in sea levels, [land] expanded far north, forming a massive Arctic plain in Western Beringia covered by grasslands. Attracted by its high numbers of megafauna, this region provided a habitat for the Paleolithic human population that was well adapted to the extreme climate and capable of successfully hunting the woolly mammoths. We speculate that during the Last Glacial maximum, Kotelny Island was host to the human population that may have been the Native American founder population, whose origin remains unknown.”

The island is largely inaccessible most of the year under normal circumstances, and certainly more so during a global pandemic, but the team intends to return regularly as soon as they can. They hope to uncover further evidence of Paleolithic hunters, from the remains of the animals they felled to the camps themselves. The relatively few researchers who have access to this area, and thus the comparatively few discoveries that have been made so far in an area that “froze during the time of mammoths about 15,000 years ago,” per Protopopov, almost ensures exciting future revelations.