Picture this: It’s about 20 million years ago, and you’re inside the giant womb of an extremely pregnant Otodus megalodon. Everything’s hunky-dory — some baby sharks have already hatched, and others are on the way. But before any more of those egg-bound brethren can emerge, one of the baby sharks wriggles over and gobbles them up. That fish is going places.

According to a paper published today in the journal Historical Biology, it was a baby-shark-eat-baby-shark world for megalodons, which were born already over 1.83 m long. The megalodon babies presumably were birthed in small litters similar to modern lamniform sharks, as opposed to egg-laying shark species.

“The new study is really the first of its kind for megalodon,” Kenshu Shimada, a paleobiologist at DePaul University in Chicago and research associate at Kansas’s Sternberg Museum in Kansas, wrote in an email. “It’s given us good insight into its size at birth, reproductive mode, and growth pattern.”

Despite being one of the most familiar faces among ancient animals, certainly among ancient sharks, precious little is known about the megalodon. Since the shark was cartilaginous, not much has been found besides its namesake teeth, which turn up often and in abundance.

In the new study, lead author Shimada and colleagues looked at one of the very few well-preserved vertebral columns of a megalodon, which reportedly was excavated from Antwerp when the city was being fortified in the mid-19th century.

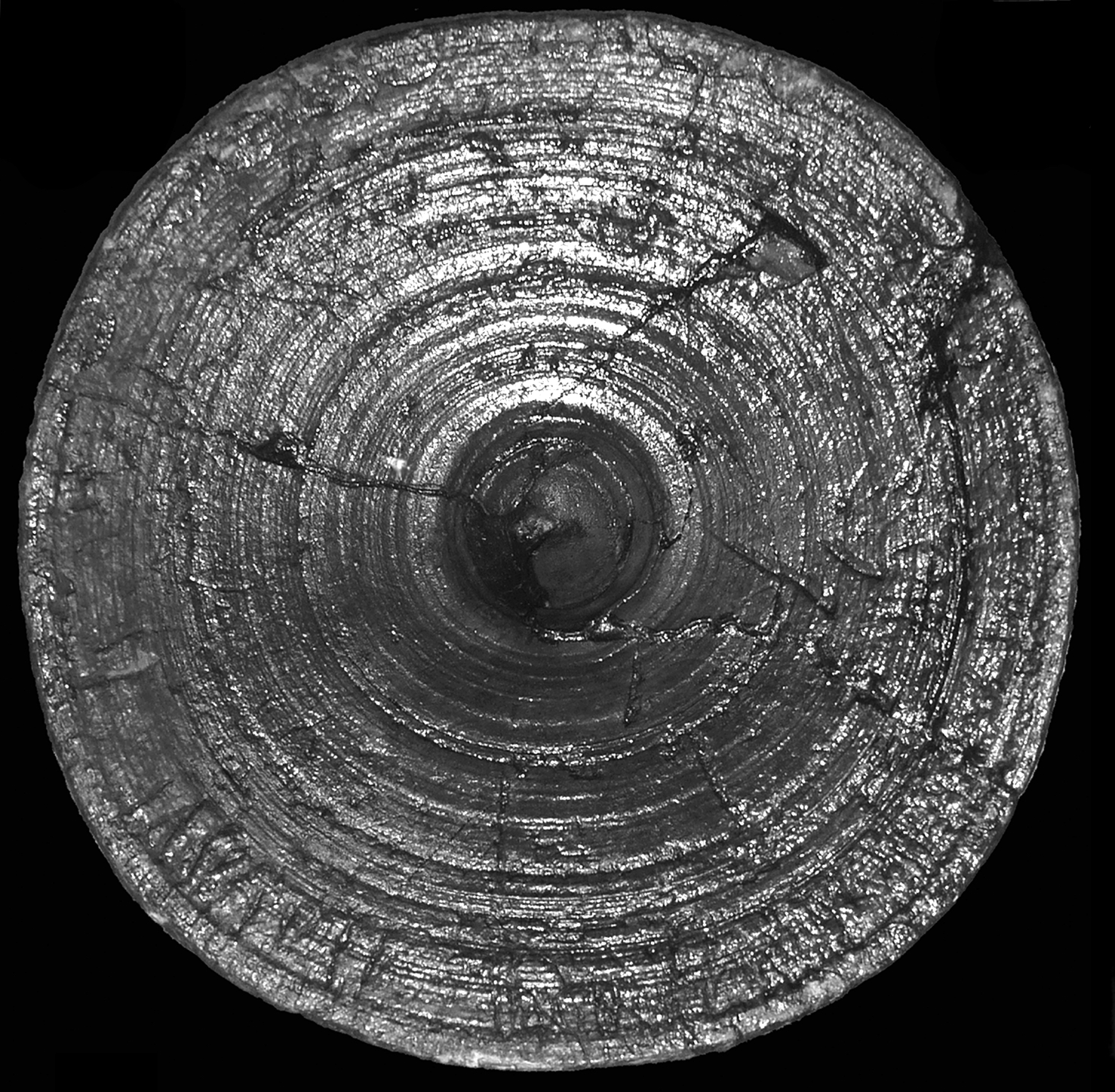

Megalodon vertebrae are like trees — for each year of age, the shark’s bone gets another concentric ring of calcified bone. That made ageing the shark at death simple arithmetic — the predator was 46, about half what Shimada’s team estimated the megalodon’s lifespan could realistically be. Though the lower bound of the estimated lifespan was 88 years, Shimada’s team acknowledged the shark could potentially get much older, though, given the harsh conditions of ocean life several million years ago — even for an apex predator — most megalodons would not have reached such an age.

Guessing the shark’s birth size came simply from extrapolating from the vertebrae’s size in that first year represented in the rings. Though most of these sharks likely didn’t grow to the 18.29 m length often touted when the famous fish is discussed, an average megalodon still would’ve made the great white look puny.

Part of the recipe for success for a young megalodon, the team suggests, may have been oophagy, the filial cannibalism observed in all modern lamniforms. This cannibalism happens while the siblings are still in eggs and provides the sharks further along in their life cycle with nutrients to get ahead.

“Embryos of present-day lamniform sharks do already possess teeth, but they are generally peg-like, presumably suited to puncture and tear up eggs,” Shimada said. “The mother’s womb in present-day lamniform sharks secretes a lipid-rich fluid, so I envision embryos to be developing in a nutrient-rich environment slurping soft eggs and the fluid.”

Delicious — and a great way for a young shark to make sure it’s at the safe size of 1.83 m long before entering a sea filled with other huge predators.

Based on the vertebral rings, Shimada’s team was also able to discern the shark’s rate of growth from birth to age 46. They found that the megalodon had a gradual growth rate of about 6.3 inches per year for every year of its life — so this shark was around 9.14 m long when it died.

The megalodon’s growth pattern suggests that slow and steady wins the race, but that’s only half the story; it probably helps to eat your siblings.