The forensic analysis of a 3,600-year-old mummy is providing fascinating new insights into a pivotal Egyptian pharaoh and the circumstances of his exceptionally violent death.

Seqenenre-Taa-II was likely executed by multiple assailants after being captured on the battlefield, according to new research published in the science journal Frontiers in Medicine. The new research also shows that the pharaoh’s body had already entered into a state of decomposition prior to mummification, and his embalmers did the best they could to conceal his very serious facial injuries.

Seqenenre ruled over southern Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1650 to 1550 BCE) — a tumultuous time in which the Hyskos, a foreign power, ruled Egypt’s northern territories. The Hyskos took control of Avaris, the capital city, but they allowed Egyptian rulers to maintain control over the south, provided they paid tribute to the Hyskos king. Today, Avaris is known as the archaeological site Tell-el-Dabbaa.

Known as “The Brave,” Seqenenre tried to oust the Hyskos, but as the new research affirms, he was likely killed in the attempt — and in brutal fashion.

The pharaoh’s mummy, discovered in the 1880s, was analysed with X-rays in the 1960s, revealing a series of severe head wounds. This led to all sorts of speculation about the circumstances of his death, leaving historians wondering if he died on the battlefield or at the hands of murderous plotters. It was also unclear as to why Seqenenre — a pharaoh of high standing — had such a shoddy mummification.

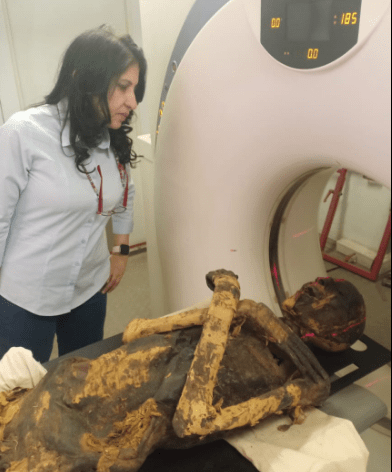

In an effort to answer these questions, a team of archaeologists led by Sahar Saleem, a professor of radiology at Cairo University, used computerised tomography (CT) to re-analyse the mummy, which is kept at the Cairo Egyptian Museum. The research team, which included Zahi Hawass, an archaeologist with Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities, also reviewed the archaeological literature and evaluated five Asian weapons previously uncovered at Tell-el-Dabaa. These weapons — three daggers, a battle-axe, and a spearhead — date back to the Asian Middle Bronze Age Culture II, which coincides with the reign and death of Seqenenre.

The new analysis showed that the mummy is in very bad shape. The head is no longer connected to the body, many vertebrae and ribs are loose, and there’s very little soft tissue or muscles left on the bones.

The investigation showed that Seqenenre was around 40 years old when he died and that he stood 5’6” (167 cm) tall.

A desiccated, shrunken brain was found on the left side of the skull, and it doesn’t appear that any attempt was made by his embalmers to remove it, unlike his other organs. In fact, no evidence of embalming materials could be found.

What’s more, the body was already decomposing at the time of mummification, and it appears the embalmers “deliberately concealed” the pharaoh’s injuries, “likely as a desperate attempt to beautify the injured corpse of the King,” wrote the study authors. Taken together, this suggests the pharaoh did not die in his palace, as he would’ve been preserved according to the traditions of the time.

Seqenenre had no bodily fractures, but his head and face were severely injured. The large fracture on his forehead was attributed to a “heavy sharp object like a sword or an axe,” according to the paper. The location of this injury suggests an assailant delivered the killing blow from a position above the pharaoh. A double-edged weapon, like a bronze battle-axe, likely caused the “gaping fracture” above Seqenenre’s right eyebrow, and some kind of blunt force object, like an axe handle, was responsible for multiple blows on the pharaoh’s face, according to the paper. A penetrating wound below the mummy’s left ear and into the base of his skull was likely caused by a spearhead.

The researchers said any one of these injuries would’ve been fatal; such “severe craniofacial trauma could have caused fatal shock, blood loss, and/or intracranial trauma,” they wrote. The CT scans confirmed that all injuries to the skull and face were inflicted at the time of death, as there was no evidence of healing.

The condition of the pharaoh’s hands and wrists points to a condition known as “cadaveric spasm,” which “typically affects the hands and limbs of individuals who were subjected to violent deaths and whose nervous systems were disturbed at the moment of death,” wrote the authors. In this case, the peculiar and unorthodox hand positioning suggests the pharaoh’s wrists were tied together, likely behind his body, when he was killed. This could also explain why Seqenenre had no defensive wounds on his hands or arms.

Given these findings, it seems likely that the pharaoh was executed on the battlefield. As the study authors write:

The strong hit must have caused the King to fall down, possibly on his back. The King may have received several attacks from the assailant with the Hyksos battle axe, possibly using its blade to inflict the fracture above the right eyebrow…Then a thick stick (possibly the handle of the axe) was used to smash the nose and the right eye of the King. The assailant hit the King’s left side of the face with the axe. Another assailant at the left side used a spear horizontally to pierce deeply the lower part of the left ear…and reached the foramen magnum [the part of the skull that attaches to the spinal column]. We assume that the King was dead at this point, and that his body was rolled to lie at his left side where he received several blows to the right side of the skull possibly by a dagger. The dead King likely stayed lying down on his left side for some time enough for the body to start decomposition as the brain shifted to this dependent side.

Yikes. That is some seriously nasty business. It also makes sense that the pharaoh’s body wasn’t immediately gathered from the battlefield, as access to the site was probably limited, given the conflict. His embalmers, working with a badly mutilated body that had already started to waste away, did the best they could with a bad situation.

[referenced id=”1669443″ url=”https://gizmodo.com.au/2021/02/analysis-of-ancient-egyptian-mummy-reveals-unusual-mud-ritual/” thumb=”https://gizmodo.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/04/l5ssvsg0oyymugxrikbu-300×168.jpg” title=”Analysis of Ancient Egyptian Mummy Reveals Unusual Mud Ritual” excerpt=”The discovery of a hardened mud carapace wrapped around a 3,200-year-old mummy has brought a previously unknown ancient Egyptian burial practice to light.”]

Of course, this is all speculation, but speculation based on scientific evidence. We’ll likely never know the exact circumstances of Seqenenre’s death, but this paper, as grim as it is, suggests his final moments were thoroughly unpleasant.

All that said, the pharaoh’s death was not in vain, as it led to the eventual unification of Egypt. Seqenenre’s death “motivated his successors to continue the fight to unify Egypt and start the New Kingdom,” explained Saleem in a statement.