Jaw-dropping footage taken in Guam shows a previously unknown climbing strategy employed by brown tree snakes.

New research published in Current Biology describes a fifth mode of locomotion in snakes, the other four being sidewinding, rectilinear, lateral undulation, and concertina. The newly discovered form of climbing, dubbed “lasso locomotion,” could result in better mitigation strategies to protect the native bird population from the invasive brown tree snake (Boiga irregularis). The snakes were inadvertently introduced to the island in the 1940s and 1950s, after which time the native bird population began to plummet.

In fact, this lasso locomotion — in which the snakes create a loop with their bodies to generate friction — may be contributing to the “success and impact of this highly invasive species,” allowing them to exploit resources that “might otherwise be unobtainable,” wrote the authors, led by ecologist Julie Savidge from Colorado State University, in their new paper. The lasso technique likely evolved to help them climb trees, but the snakes are now using the method to climb artificial structures like utility poles.

That these nocturnal snakes are slithering amok on Guam is a serious problem. Most of the native birds on the island have disappeared since the snakes’ arrival, with Micronesian starlings and a species of cave-nesting birds being the last to survive. The starlings are of particular ecological importance, as they distribute fruits and seeds across the island. What’s more, these snakes, being proficient climbers, also cause damage to human infrastructure, and they’re responsible for frequent power outages on the island. Thus, it’s important that scientists figure out what brown tree snakes can and cannot climb.

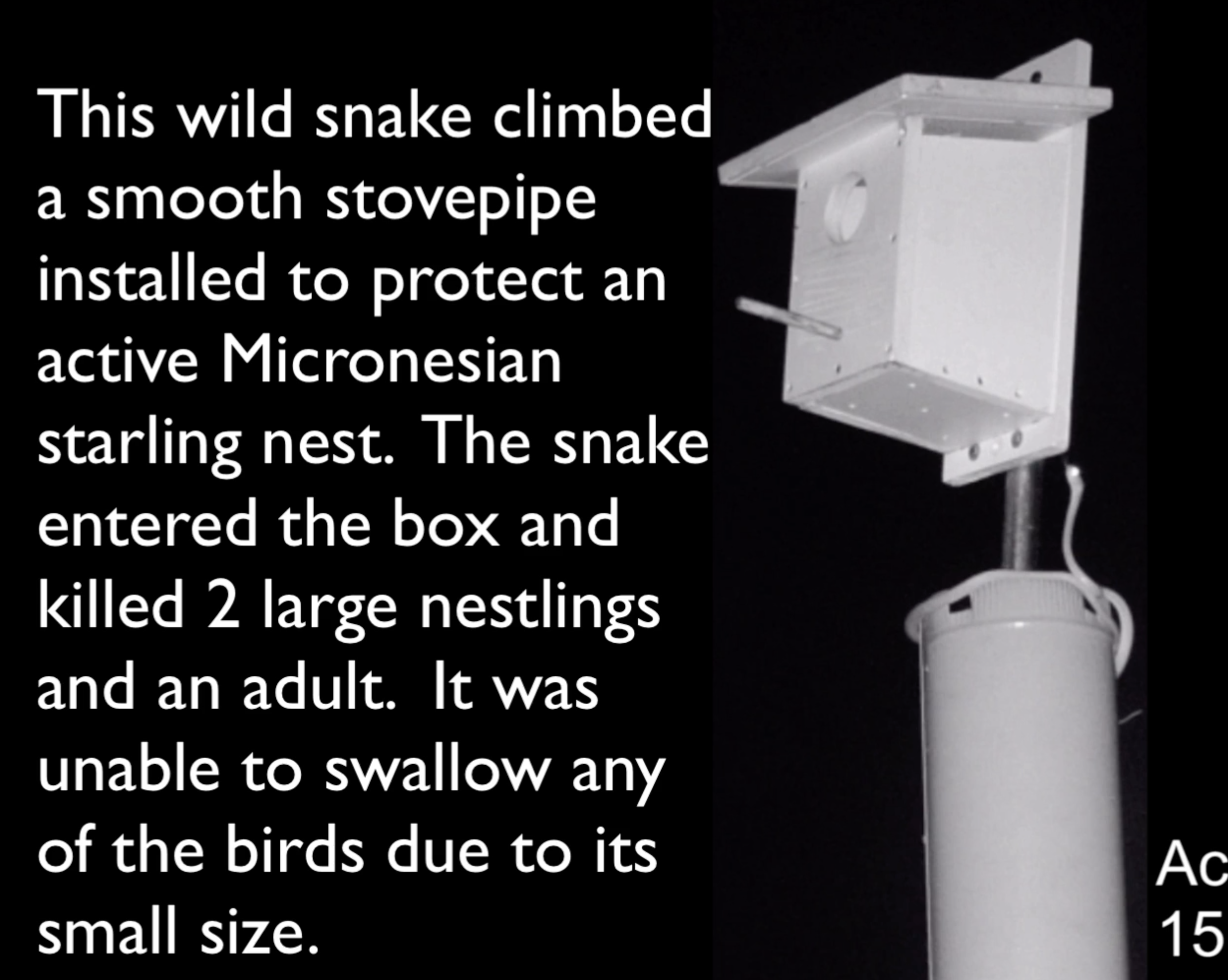

Savidge, along with CSU ecologist Thomas Seibert, was studying the nesting habits of Micronesian starlings when they stumbled upon the finding. To protect the birds, a nest box was placed atop a tall pole.

“And although we knew the starlings could successfully nest in our nest boxes on larger round utility poles, utility poles are limited in distribution and we wanted to know if we could protect birds nesting in bird boxes on top of EMT poles that had stovepipe baffles attached below the nest box,” explained Savidge in an email. “Stovepipe baffles have been used to keep other snakes and raccoons away from nest boxes on poles in the yards of bird-watchers.”

The scientists were testing the ability of snakes to climb this baffle when the new form of locomotion was discovered.

“We didn’t expect that the brown tree snake would be able to find a way around the baffle,” said Seibert in a CSU press release. “Initially, the baffle did work, for the most part. Martin Kastner, a CSU biologist, and I had watched about four hours of video and then all of a sudden, we saw this snake form what looked like a lasso around the cylinder and wiggle its body up. We watched that part of the video about 15 times. It was a shocker. Nothing I’d ever seen compares to it.”

In total, the scientists observed five different snakes performing the manoeuvre, climbing up smooth cylinders between 15-20 cm in width. A typical brown tree snake measures around 138 cm long.

Intrigued — if not horrified — by the video, the team recruited Bruce Jayne from the University of Cincinnati, an expert on the mechanics of snake locomotion, who helped study and describe the previously unknown form of climbing. On closer inspection, Jayne noticed how the snakes form bends within the loop of the “lasso,” which helps the animal move upwards.

“The loop of the ‘lasso’ squeezes the cylinder to generate friction and prevent slipping,” said Jayne in an email. “The little sideways bends within the loop of the lasso serve two important functions. First, they provide a mechanism for tightening the loop by using the largest groups of muscles within the body of the snake, and second, they move the snake upward bit by bit as they move toward the tail of the snake and around the circumference of the cylinder.”

Typically, tree-climbing snakes, when using the concertina form of locomotion, bend sideways to latch onto two places at once. This is fundamentally different, however, as the loop of the lasso is used to grip a single spot on the cylinder.

It’s an impressive feat, but the lasso method requires intense physical effort. The snakes move upwards very slowly, breathe heavily, take frequent breaks, and often slip. The scientists don’t know how common this technique might be in other species or places, but it’s possible other snakes can do this.

[referenced id=”1515235″ url=”https://gizmodo.com.au/2020/09/horrified-scientists-watch-snakes-feasting-on-the-organs-of-living-toads/” thumb=”https://gizmodo.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/30/urvjmn5ts9azbvhwvcn2-300×168.jpg” title=”Horrified Scientists Watch Snakes Feasting on the Organs of Living Toads” excerpt=”Biologists in Thailand have documented a behaviour never seen before in snakes, in which the limbless reptiles eviscerated and consumed the organs of living toads.”]

“To date, I am not aware of anything remotely similar to the lasso locomotion of brown tree snakes in other species,” said Jayne. “However, there are more than 3,500 species of snakes with hundreds of species that climb trees, and sometimes animals in nature perform rare behaviours that have never been observed in laboratory conditions. Thus, much remains to be learned about this issue.”

Equipped with this knowledge, the team now plans to build better protective barriers and study this snake in more detail to fully understand how it pulls off this mind-bending trick.

This article was originally published in January 2020.