As long as the original Superman has had counterparts like Steel and, more recently, Final Crisis’ Calvin Ellis of Earth-23, there have been comics fans who struggled to comprehend — and often pushed back against — the idea of a Black Superman.

This small-minded and particularly pervasive quirk of the larger Superman fandom isn’t unique to Superman or DC Comics. The reluctance some people have to consider the idea of a Black Superman comes from a similar place as the hostile reactions to Marvel Comics’ Miles Morales and Sam Wilson becoming Spider-Man and Captain America, respectively. It’s not just that people don’t like change, but rather that change in the context of legacy characters’ mantles being passed on is often interpreted as erasure when the mantles are given to Black people. This is a remarkably dim way of responding to comic books’ very real need to find ways to keep stories fascinating, particular for longstanding characters like Superman who are not just old (over 80 years now), but part of the larger fabric of pop culture in ways that newer characters generally don’t tend to be.

You could see this sort of response and the energy behind it in many people’s reactions to Warner Bros.’s recent announcement that Captain America and Black Panther writer Ta-Nehisi Coates would pen the studio’s next Superman movie. This is also what made Bridgerton star Regé-Jean Page having to respond to allegations that his Blackness factored into being rejected for the role of Superman’s grandfather on Syfy’s Krypton upsetting, but wholly unsurprising. The situation with Page has become part of a larger series of allegations of discrimination leveled against Geoff Johns — who has recently made a point of asking to be identified as Lebanese American — that’s important to pay attention to as it relates to Warner Bros. and DC’s future projects. But the weirdness that arises whenever Blackness and the concept of Superman intersect is something worth considering in its own right, and not simply because it’s something that relates to current news.

[referenced id=”1675691″ url=”https://gizmodo.com.au/2021/02/a-superman-solo-film-is-on-the-way-from-ta-nehisi-coates-and-j-j-abrams/” thumb=”https://gizmodo.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/27/zrwmpmle0tnxnbylzw1o-300×169.jpg” title=”A Superman Solo Film Is on the Way From Ta-Nehisi Coates and J.J. Abrams” excerpt=”A new Superman movie is finally in the works from a superhuman team of talents.”]

As is always the case with legacy comics characters, if you look far back enough it isn’t long before you come across stories “of their time” that reflect the distinct lack of voices that didn’t belong to straight, white men with two-dimensional ideas about people who were unlike them. Superman’s always been a symbol for an idealised form of the American dream and a mythic idea of morally sound justice. But in comics like Giant Superman #239 from 1971, an issue including multiple stories from writers Otto Binder and artists Wayne Boring and Stan Kaye, you can see how DC Comics has always had a difficult time addressing Blackness in the context of Superman stories as its own identity rather than something that exists in contrast to whiteness.

In addition to following Superman’s adventures with a version of the Greek god Hercules, Giant Superman #239 also features a story in which the last son of Krypton battles Titano the Super-Ape, a King Kong-like beast who gains his massive size, strength, and Kryptonite energy eye beams from an experiment that sends him into space. Obvious as Titano’s origins as a Kong analogue have always been, his presence within DC’s canon has been understandable because of the large chunks of space that King Kong and Superman take up in pop culture at large.

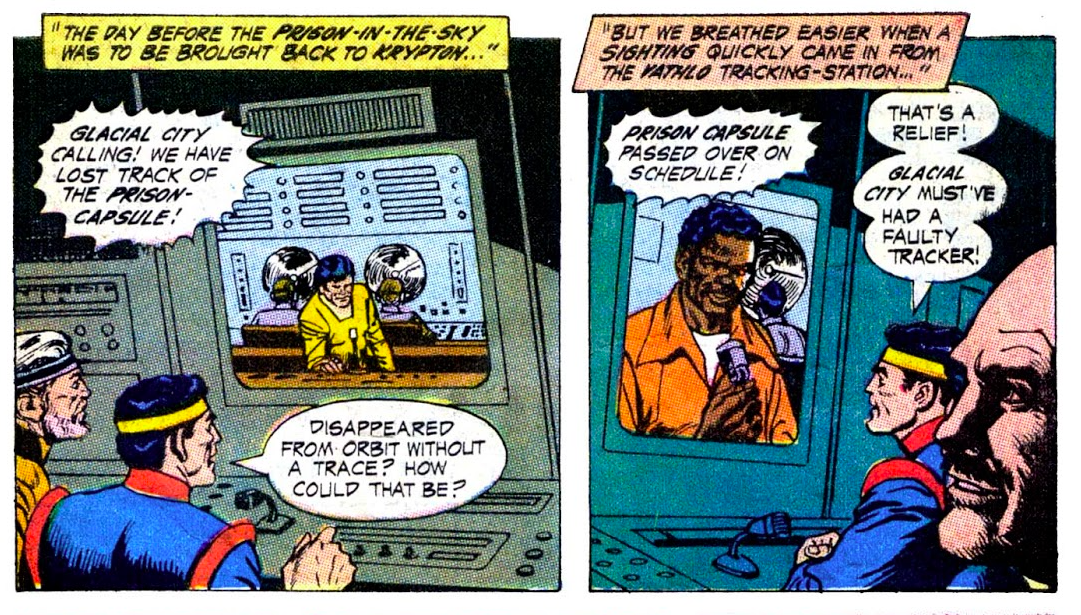

What was telling about Titano’s appearance in Giant Superman #239, though, was the comic’s supplementary story about Superman’s homeworld of Krypton, told with two pages of maps and scenes at the end of the issue set before Krypton’s untimely destruction. Though there had been a small appearance of an unnamed, brown-skinned Kryptonian in 1971’s Superman #234, Giant Superman #239 established the existence of Vathlo, an island in the middle of Krypton’s Dandahu Ocean where the planet’s “highly-developed black race” lived, far away from white Kryptonians.

Unexamined as Vathlo’s existence has gone for the bulk of DC Comics’ history, its creation immediately raised a number of questions about Kryptonian society that Superman comics, and much of the fandom, have never been particularly keen on asking. By presenting Vathlo as an island full of Black Kryptonians without explaining what they were doing there, Giant Superman made it impossible not to regard it as being a reflection of our reality’s history of racial segregation, even if that wasn’t DC’s express intent. This lack of worldbuilding more than anything else is what differentiated Vathlo from Marvel’s Wakanda, which had been introduced in its Fantastic Four comics just a few years prior.

It doesn’t exactly feel coincidental either that Vathlo’s first proper appearance in DC Comics came just pages after a story in which the Man of Steel bests a humongous ape who expresses interest in Lois Lane. In Titano, through his connections to Kong, exists a significant chunk of Western culture’s deeply racist, historical fascination with Africa — often framed as a dark and mysterious place full of untold wonders. Similar to the way that Kong’s only been moved but so far from the ugliness of his narrative roots, Vathlo went on to become a seldom-touched upon aspect of Superman’s mythos. That was understandable to a point given that Krypton doesn’t exist in the present day, but a lack of fleshing out what Vathlo was and why Black Kryptonians lived there made various references to the island inadvertent reminders: Apparently Krypton was segregated as hell, something that a man of Superman’s morals might want to inspect a bit more deeply.

Both of DC’s most prominent Black Supermen, Steel (created by Louise Simonson and Jon Bogdanove) and Final Crisis’ Kalel (created by Grant Morrison and Doug Mahnke), were introduced as reactions. They were answers to things happening in the larger world that led to DC’s creative teams crafting these characters. In Steel’s case, the death of Superman presented DC with the opportunity to introduce a new host of heroes attempting to carry the torch Kal-El left as part of an ongoing story about how his death fundamentally changed the world.

While Kalel wasn’t created in response to any one specific DC character, he was very clearly modelled after Barack Obama, the then-newly elected President of the United States. His two terms in office changed the tone of American politics just by dint of the reactionary hostility it prompted conservatives to centre as a matter of policy. Rather than living a double life as an average reporter like Clark Kent, “Calvin Ellis” went on to become President of the United States, all without the world ever learning that his parents were Kryptonians from Earth-23’s Vathlo Island. Again, because Vathlo was never given more substance beyond being a destroyed island of Black aliens, it never had a chance to become much more than a throwback to a time when stories about deepest, darkest Africa were featured in adventure comics.

Even less has been revealed about Val-Zod, created by writer Tom Taylor and artists Nicola Scott and Robson Rocha in 2014, the second Superman of the Earth-2 reality. He was introduced as another escapee of Krypton’s destruction who finds refuge on Earth alongside Kara Zor-El and her famous cousin. Val-Zod, a pacifist agoraphobe whose fear of being outside kept his powers substantially nerfed for some time, vaguely read like a clumsy commentary about incarcerated peoples’ difficulties adjusting to the outside world. His arc of becoming Earth 2’s Superman in the time before the creation of the New 52 universe is one worth reading, and you can see how elements of those comics might lend themselves to an interesting new cinematic entry into the Superman canon down the line.

In order for any of that to work, though, the artists, publishers, and studios that are responsible for iterating on this IP have to make peace with the reality that DC’s history of Black Supermen just leaves a lot to be desired. Rather than running away from it (and pretending that it hasn’t influenced how the fandom thinks about Superman), they’re all in a position to get down to brass tacks and give this piece of Superman’s mythos the same kind of attention that people do the character’s costumes.