On August 30, 1995, 10-billion-year-old light from the early universe finally hit the Compton Gamma-ray Observatory, which was circling in Earth orbit. An Australian research team is now reporting that the gamma-ray burst contained evidence of an exceedingly rare intermediate-mass black hole, the sort that would help fill a hole in our understanding of these cosmic enigmas.

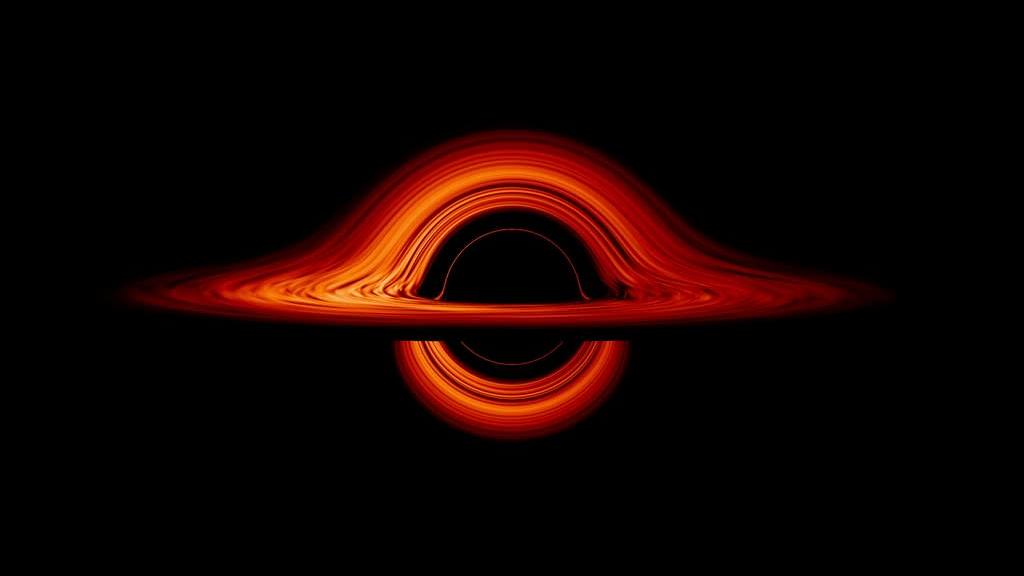

Black holes are typically categorised into in three sizes. The smallest are stellar-sized black holes, which, as their name suggests, are roughly the mass of some stars and can be anywhere from a few to a hundred times the mass of our Sun. Then there are the little-known and only tentatively described intermediate-mass black holes, which range from 100 solar masses to 100,000 solar masses. At the far end of the scale are supermassive black holes, which are 100,000 solar masses or larger. Some are billions of times the size of our Sun, like the black hole famously imaged in 2019.

Intermediate-mass black holes exist, but, unlike their bigger and smaller compatriots, they offer little to our telescopes trying to spot them. Possible midsize black holes are rarely found, though astrophysicists have a few ideas about where to look and have even named a few candidates in recent years. There are only a handful of observed objects suspected of being an intermediate-mass black hole.

The recent team’s analysis of the 26-year-old data was published this week in the journal Nature Astronomy. It’s not the first reported intermediate-mass black hole candidate, but is the first one detected using gamma rays.

[referenced id=”1113679″ url=”https://gizmodo.com.au/2018/06/scientists-find-stronger-evidence-for-new-kind-of-black-hole/” thumb=”https://gizmodo.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/20/hfyzpslgcpaoxmk1xoqk-300×169.jpg” title=”Scientists Find Stronger Evidence For New Kind Of Black Hole” excerpt=”We’ve seen supermassive black holes at the centres of galaxies tearing stars to shreds. We’ve detected the energy wave from relatively tiny black holes slamming together to create a wobble in space-time a billion light-years away. But what about the medium-sized black holes in between these extremes?”]

When intermediate-mass black hole candidates are brought forward, it’s typically through evidence that implies an object of their gravitational and massive description. Supermassive black holes pull so many bright things close to them that they’re easy to spot, and stellar-mass black holes are often seen being orbited by stars. Intermediate black holes stay in the shadows, but if studied further, they could help explain how larger black holes got so big and how many total black holes might be out there.

“The ones in our galaxy, wherever they may be, must not be accreting gas, so they’re either floating freely through space without anything falling into them and making them glow, or they’re in the centre of globular clusters, and they’re shielded by all the stars,” said James Paynter, an astrophysicist at the University of Melbourne in Australia, in a video call. “Wherever these intermediate-mass black holes are, they’re not doing anything that betrays the fact that they’re there.”

Looking at the Compton data set of thousands of observed gamma-ray bursts, Paynter’s team ran through each burst using an automated script, looking for rapid, near-identical consecutive bursts. That signature would suggest that a single burst occurred but took two paths to travel around one huge object in the cosmos. (Think of two rivulets of water rushing downstream around a boulder.) That would cause the gamma-ray burst to be recorded twice but have a very similar look in the data; it would be an example of “gravitational lensing,” in which the extreme gravity of an object in the cosmos bends light around itself.

The team found only one burst that fit the bill, a one-two punch of gamma radiation milliseconds apart. Characteristics of the lensing event allowed the team to approximate the mass of the object that caused it, which they said could only have been a few things: a globular cluster (a tightly bound knot of stars), a dark matter halo (basically an invisible aura of gravity that extends beyond a massive object), or a black hole. They eliminated the former two as possibilities, leaving an intermediate-mass black hole as the prime suspect for the lensing.

Tod Strohmayer, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre who is unaffiliated with the new paper, said that gamma-ray bursts “come in two flavours.” Some are relatively long, running from tens to hundreds of seconds, and others are short — mere milliseconds. The fact that this burst was in the latter group, but happened twice, indicates a lensing event, he said.

“It’s an interesting finding in that it seems to fit what you’d expect if it was indeed a gravitationally lensed event,” said Strohmayer in a phone call. “It’s consistent with that interpretation, but at the moment, there’s this one indication that that’s what it could be… you’d have to observe a lot of gamma-ray bursts if you were going to see more of these.”

[referenced id=”1671930″ url=”https://gizmodo.com.au/2021/02/astronomers-looking-for-one-black-hole-may-have-found-an-entire-squad/” thumb=”https://gizmodo.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/13/bsck88yatuic7kaxqwqz-300×169.png” title=”Astronomers Looking for One Black Hole May Have Found an Entire Squad” excerpt=”About 7,800 light-years away — within our galactic neighbourhood — is globular cluster NGC 6397, basically a wad of stars held together by gravity. That bunch of stars was previously thought to have an intermediate-sized black hole at its centre. But upon further inspection, a team from the Paris Institute…”]

Intermediate black holes matter because we don’t know how supermassive black holes get so large. They could be supermassive from the get-go, spawned out of the primordial universe, or they could be intermediate black holes that accrete matter and swell in size. They could also be formed when intermediate black holes, themselves from the primordial universe, merge with one another, coalescing into the behemoths we’re familiar with today. This paper doesn’t solve the mystery, but it raises an intriguing new means of increasing our midsize black hole sample. With new candidates for intermediate-mass black holes, astrophysicists have new opportunities to probe what gave rise to the largest objects in the universe, which formed long enough ago that their mass is confounding.

A useful development, Strohmayer said, would be if an intermediate-mass black hole with an orbiting companion star came along. That would help certify the status of any of these candidate objects as the real thing. As fortunate it is that the Compton Observatory picked up the echoed burst, it unfortunately was a piece of pre-millennium technology. At the resolution it was operating, the observatory was not able to detect where in the universe the burst came from — merely that it arrived.

So the signal received in 1995 is tantalising. Somewhere out there, something big forced light around itself, showing us another possible black hole lurking in the in-between. Paynter’s team has only gone through about a quarter of the observatory’s data, so it’s possible more events will be picked out.