For the past few months, millions of Chrome users have been roped into Google’s origin trials for the tech meant to replace the quickly crumbling third-party tracking cookie. Federated Learning of Cohorts — or FLoC, for short — is a new kind of tracking technique that’s meant to be a friendlier, more privacy-protective alternative to the trackers we all know and loathe, and one that Google seems determined to fully implement by 2022.

As you might expect from a Google privacy push, people had concerns. A lot of them. The Electronic Frontier Foundation pointed out that FLoC’s design seems tailor-made for predatory targeting. Browsers like Firefox and Brave announced they wouldn’t support the tech in their browser, while DuckDuckGo literally made an extension to block FLoC entirely. While this trial keeps chugging along, academics and activists keep on finding loopholes that contradict FLoC’s privacy-preserving promises.

They aren’t the only ones. Digiday reported this week that some major players in the adtech industry have started drawing up plans to turn FLoC into something just as invasive as the cookies it’s supposed to quash. In some cases, this means companies amalgamating any data scraps they can get from Google with their own catalogues of user info, turning FLoC from an ”anonymous” identifier into just another piece of personal data for shady companies to compile. Others have begun pitching FLoC as a great tool for fingerprinting — an especially underhanded tracking technique that can keep pinpointing you no matter how many times you go incognito or flush your cache.

In the middle of all this, the most popular browser in the world, Chrome, is just… looking the other way.

“Even if Google didn’t think about these things when it was designing this technology, as soon as they put this stuff out in public back in 2019, this is exactly what advocates were saying,” said Bennet Cyphers, a technologist with the EFF who focuses on adtech. “You could take one look at this thing and immediately know it’ll just turn into another tool for fingerprinting and profiling that advertisers can use.”

What is FLoC supposed to be and how’s it different from cookies?

Google’s pitch for FLoC actually sounds pretty privacy forward at first glance. The third-party cookies FLoC is meant to replace are an objective scourge to the web writ large; they map out every click and scroll made while browsing to create countless unique profiles, and spam those profiles targeted ads across multiple sites. FLoC nixes that individualized tracking and targeting, instead plunking people into massive anonymous cohorts based on their browsing behaviour. These cohorts are thousands of people deep, and get wiped every week — meaning that (in a perfect world), your assigned cohort can’t be used to pick you out of a crowd, and can’t be used to target you in the long term. At least, that’s how it’s being sold.

On top of this, your ever-shifting FLoC ID is labelled with a meaningless jumble of letters and numbers that only Google can decipher, and that jumble is held locally on your browser, rather than in the hands of some third-party company you’ve never heard of. Altogether, FLoC’s meant to turn you into a nameless drop in an inky sea of data, where everything about you — your name, your web history, what you ordered for lunch — is buried deep beneath the surface.

At the start of this year, Google announced that some of these FLoC cohorts would be available for advertisers that want to see them in action through the company’s upcoming origin trials, with plans to start serving the first FLoC-targeted ads in the second quarter of this year. So far, the company reports that there’s been a whopping 33,872 different cohorts, and each cohort holds data from “at least” 2,000 Chrome customers that were opted in to the program literally overnight.

Google not only forgot to give these millions of users a basic heads up, but it didn’t give users any way to see if they’d became unwitting guinea pigs in this global experiment (thankfully, the EFF did). And if you do want to pull your browser from the trial, you’re going to need to jump through way too many hoops to do so.

What are the rules around FLoC? Haha… rules…

This early in the trials, there are literally no rules surrounding what advertisers, adtech companies, or anyone else in these trials can do with this data. That means at minimum there’s a grand total of nearly 68,000 Chrome users having their cohort data hoovered up, parsed apart, and potentially passed around for massive profits right now. (We’ve reached out to Google for comment on these trials).

It’s gone as well as you’d expect. One of the adtech giants that’s part of this trial, Xaxis, told Digiday that it’s currently “conducting an analysis” to see how FLoC IDs could be incorporated into its own cookie alternative, which they call “mookies.” Yes, really. Nishant Desai, one of the directors overseeing Xaxis’s tech operations, plainly said that those strings of numbers that FLoC spits out “are an additional dimension of how you resolve [a person’s] identity.”

Desai compared it to the IP addresses that marketers have used to target you since the 90’s. Like an IP address, someone’s FLoC ID can be pulled from a webpage without any input on the user’s part, making it an easier grab than email addresses and phone numbers that usually require a user to manually hand over the information. Like an IP address, these IDs are strings of numbers that don’t disclose anything about a person until they’re lumped in with a buffet of other data points. And like (some) IP addresses, FLoC IDs aren’t entirely static — they’re technically reset every week, after all — but once you get assigned one specific cohort, chances are you’ll be stuck with it for a while.

“If your behaviour doesn’t change, the algorithm will keep assigning you in that same cohort, so some users will have a persistent FLoC ID associated with them — or could,” Desai told Digiday.

Google’s software engineer Deepak Ravichandran put this more bluntly during a recent call with the World Wide Web Consortium (or W3C for short). When asked how stable someone’s FLoC ID was expected to be, Ravichandran replied that “an average user visits between 3-7 domains on an average day, and they tend to be fairly stable over time.”

Ravichandran noted that even if a person jumps from cohort to cohort every other week, if you take a bird’s eye view of their web browsing behaviour, it all looks pretty similar. That means even with the reset after seven days, you’re likely going to be assigned the same ID you had before, rendering the rest meaningless.

Who is using these FLoC IDs?

Xaxis is just one of the many, many (many) companies in the adtech space with these sorts of plans. Mightyhive, a San Fransisco-based data firm, told Digiday that it’s lumping users into specific “buckets,” to see if the FLoC ID their browser’s been branded with is associated with “certain actions,” like buying particular products. Adtech middleman Mediavine has gone on record saying it’s currently slurping any FLoC IDs from people visiting the 11,000-ish sites plugged into its tech, and then passing that data onto other partners responsible for parsing apart which IDs visit which specific webpages.

These so-called “Demand Side Partners” (DSPs, for those in the biz) are the ones tasked with figuring out which jumbled identifier corresponds to a new mum, a teenage TikToker, or a guy that just really, really likes dogs.

Right now, it’s worth guessing these labels will be pretty broad; in that same W3C call, Ravichandran explained that these first sets of cohorts are exclusively generated using data about the domain name a person lands on, and nothing else. Different pages on a site, or the actual content on a particular page, aren’t being considered in FLoC’s algorithm — though he hinted that might change “later this year.”

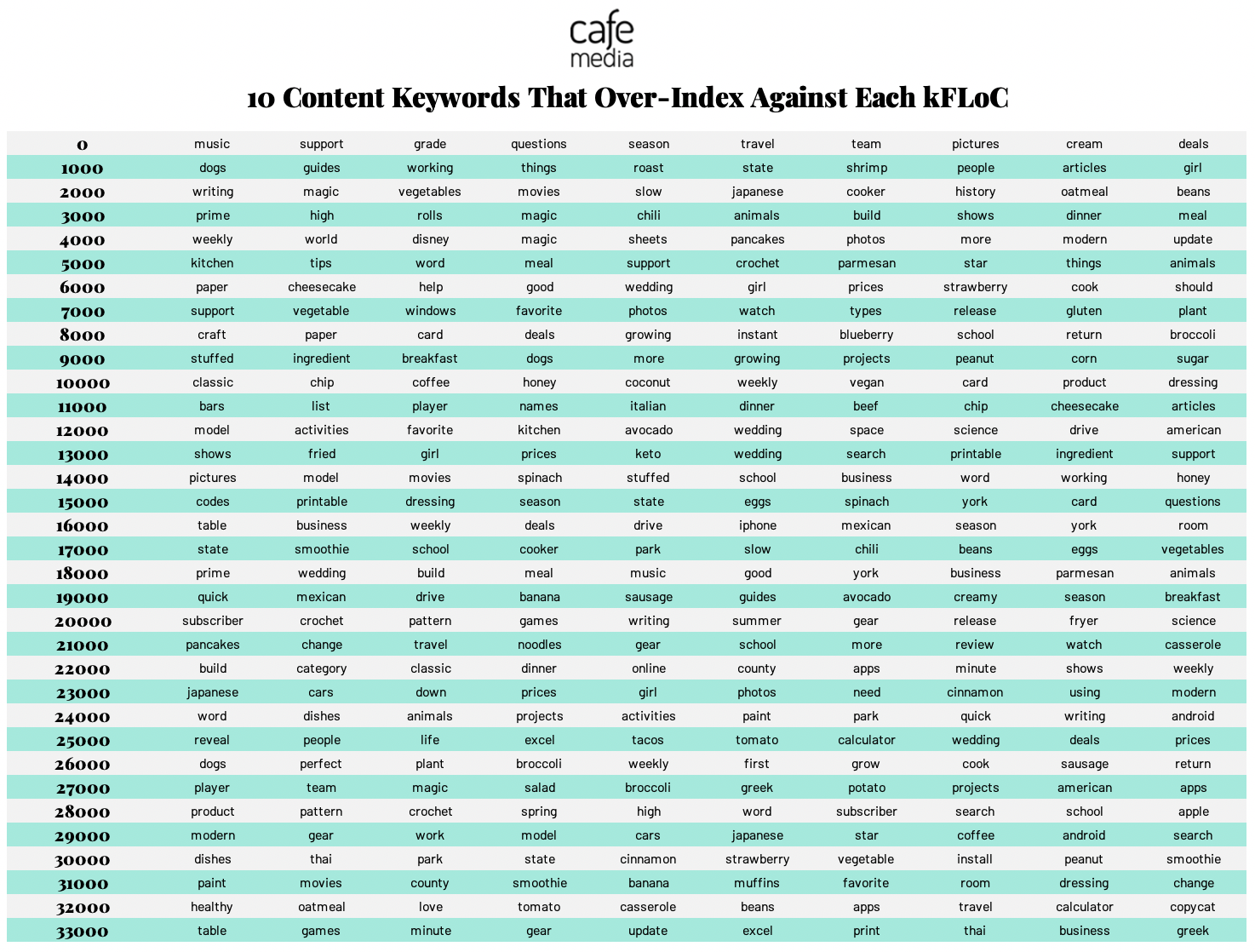

If you’re wondering how hard it is for these DSPs to decode these cryptic cohort codes, the answer is “not very.” Last month, Mozilla alum Don Marti — who now works for the ad firm CafeMedia — published a blog laying out how he roughly decoded some of the major FLoC categories that were visiting sites his company worked with. After boiling down the 33,000-ish different cohorts Google generated into 33 mega-horts, he mapped out keywords associated with the websites these ‘horts frequented.

After filtering out some of the more mundane keywords (to make the results more “meaningful”), and he ended up with… this:

In broad strokes, you can probably tell what kind of person each of these FLoCs represents. Number 32, featuring words like “healthy” and “tomato” and “apple” and (my personal favourite) “beans,” might be someone that’s really into eating organic and cooking from home. Number 20 (“crochet,” “pattern,” “writing,”) sounds like a chill person that could make you a comfy scarf. Number 15 (“codes,” “printable,” “eggs,”) sounds… well, I’m honestly not sure about that one. A tech bro that likes a good shakshuka?

You probably wouldn’t learn much about someone if you matched one of these cohorts with whatever data a major broker already had on them. Sure, you might learn that this guy’s really into magic/casseroles/dogs — but if my past experiences with magic-casserole-dog guys are any indication, you likely already knew this about them.

But what if that guy regularly visits websites centered around queer or trans topics? What if he’s trying to get access to food stamps online? This kind of web browsing — just like all web browsing — gets slurped into FLoC’s algorithm, potentially tipping off countless obscure adtech operators about a person’s sexuality or financial situation. And because the world of data sharing is still a (mostly) lawless wasteland in spite of lawmaker’s best intentions, there’s not much stopping a DSP from passing off that data to the highest bidder.

Google knows this is a problem. It even published a white paper detailing how it plans to keep FLoC’s underlying tech from accidentally conjuring cohorts based on a predefined list of “sensitive categories,” like a person’s race, religion, or medical condition. Not long after that paper dropped, Cyphers dropped a blog of his own arguing — among other things — that paper’s approach was infuriatingly half-assed.

“I mean, yeah, they tried. That’s better than not trying,” Cyphers said. “But I think their solution dodges that hard problem that they’re trying to solve.”

That “hard problem” he’s talking about is admittedly a really hard one to solve: How do you keep your most vulnerable users safe from being profiled in ways that range from life-threatening to economically devastating while still scooping up troves of data about them so other people can make money?

Google, for its part, decided to tackle this problem by combing through the browsing history of some users that are part of these trials to see if they’ve visited sites in different “sensitive categories.” A website for a hospital might be labelled “medical,” for example, or a site for a person’s church might be labelled “religion.” If a cohort traffics sites within these Forbidden Categories particularly often, Google will block that group from being targeted.

In other words, Google’s proposal assumes that people in a certain “sensitive” category are visiting specific “sensitive” websites en masse. But this just… isn’t how people browse the web; people with depression probably don’t hang out on psychiatry dot org every day, and a person who identifies as LGBT+ might not be lurking around whatever Google’s assuming a “gay website” might look like. Sure, people in these categories might show off similar browsing behaviour, but Google’s proposal reads like a fix for a world where people browse the web like robots instead of like, well, people.

At the end of the day though, Google’s on track to fully roll out FLoC by mid-2022, whether it’s ready for us or not. “If you go and look at the public FLoC Github page, there’s pages of back-and-forths between the people who designed FLoC and privacy advocates pointing out why this is such a bad idea,” Cyphers said.”And every time, the designers are just like ‘Good to know! We still think we’re right.’”