An international team of researchers has reported the discovery of hand and foot prints from Quesang, in the Tibetan Plateau. The fossil impressions, which date to between 169,000 and 226,000 years ago and seem to have been created intentionally, could represent the earliest known art of its kind.

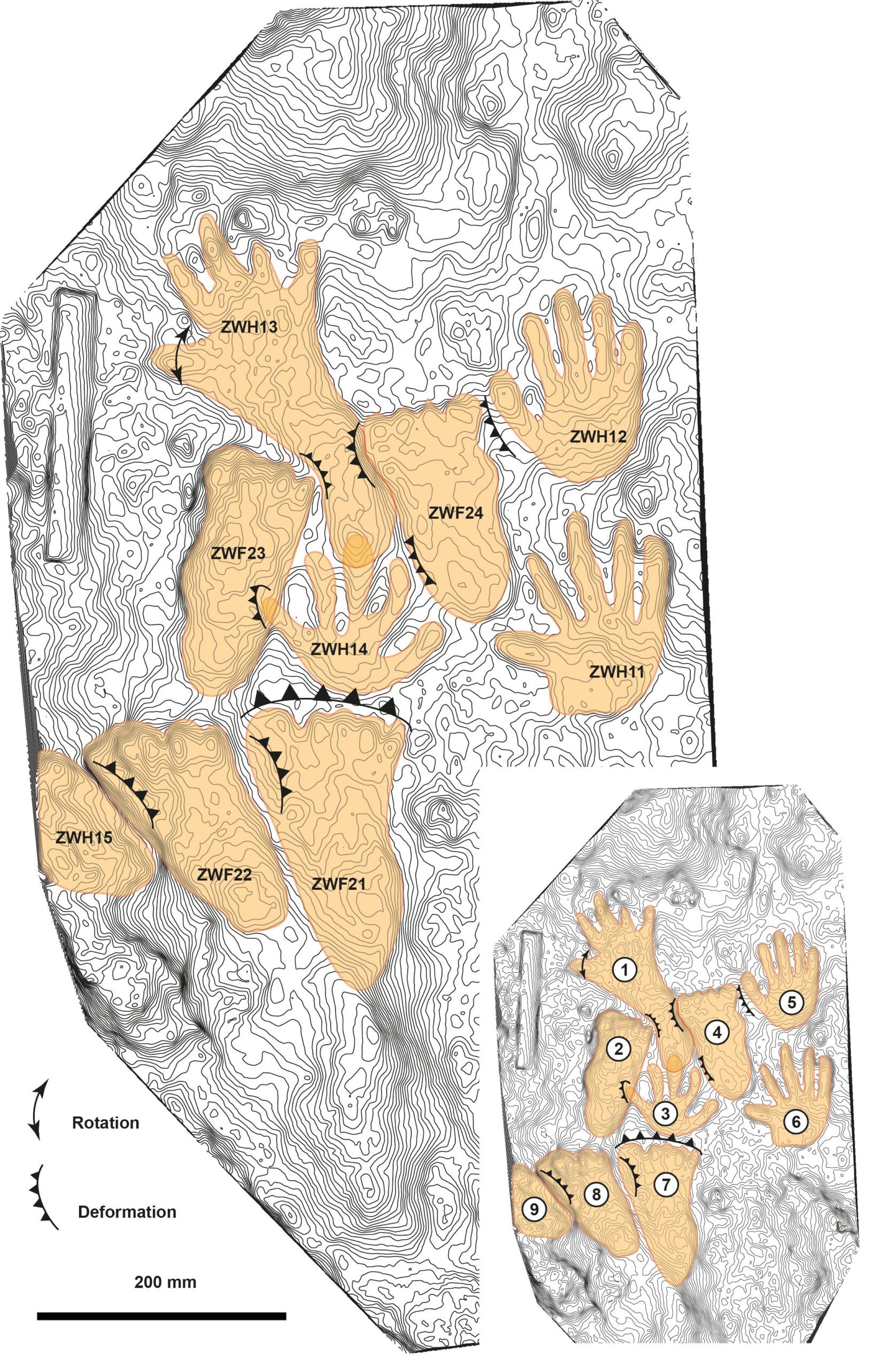

Called parietal art, this form of ancient visual expression typically crops up on cave walls but can also be made on the ground, as appears to be the case for the recent Tibet discovery. The fossil is a series of hand and foot impressions, none of which overlap.

Besides potentially being the oldest known parietal art, the site is the earliest evidence for hominins so high on the Tibetan Plateau, which sits about 3,657.60 m above sea level. The team’s work describing the fossilized prints was published this week in Science Bulletin.

“How footprints are made during normal activity such as walking, running, jumping is well understood, including things like slippage,” said Thomas Urban, a research scientist at Cornell University’s tree ring laboratory and a co-author of the new paper, in an email to Gizmodo. “These prints, however, are more carefully made and have a specific arrangement — think more along the lines like how a child presses their handprint into fresh cement.”

The prints — five from hands and five from feet — were made in what was then mud near the Quesang Hot Spring. The mud lithified into travertine rock over the millennia. Different handprints near the site were discovered by lead author David Zhang in 1988 near a modern bathhouse, but the prints that the authors believe are artwork weren’t found until 2018. Though the estimated date range for the fossils is broad, even the most recent age predates cave paintings like those at Lascaux and Sulawesi by over 120,000 years.

Based on the size of the prints, the team believes the artists could have been a 7-year-old and a 12-year-old. (The footprints were 7-year-old sized, but the handprints were larger.) That conclusion assumes that the prints were made by Homo sapiens, though, which the researchers aren’t sure about. If the species of human that made the prints was not Homo sapiens, the age guesses may be off. The timeline for the prints roughly aligns with Denisovan-like remains that were found on the Tibetan plateau, so that’s one alternative candidate for the track-makers.

Whether the prints are art at all is also up for interpretation. According to Matthew Bennett, a geologist at Bournemouth University who specialises in ancient footprints and trackways, it’s likely that these ancient imprints were intentional. “It is the composition, which is deliberate, the fact the traces were not made by normal locomotion, and the care taken so that one trace does not overlap the next, all of which shows deliberate care,” Bennett told Gizmodo in an email.

“Whether such a behaviour is artistic depends on the definition one applies — but it gets into a class of behaviours that is generally more complex that is seen with other animals,” Urban said. “Symbolic behaviours such as language, religion, and art must have simpler manifestations early in the human story — so if you’re looking for the earliest art, don’t go looking for the Mona Lisa or you’ll likely be disappointed.”