Researchers in the UK are beginning an important clinical trial of a relatively new type of weight loss, or bariatric, surgery. The minimally invasive procedure is designed to reduce the production of the so-called “hunger hormone” called ghrelin, but with less cost and upkeep than existing bariatric treatments. Similar trials are ongoing in the U.S. as well.

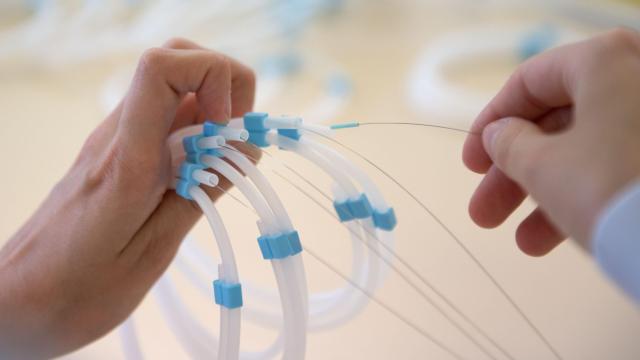

The procedure is known as left gastric artery embolisation (LGAE). It involves intentionally blocking the artery that’s the primary blood supply for the upper region of the stomach, also known as the stomach fundus — usually by sending microscopic beads to the artery through a catheter. LGAE is routinely used to stop bleeding around that area, such as the kind caused by upper stomach ulcers. But research in both animals and humans has suggested that people who get LGAE also tend to produce less ghrelin, a hormone that’s known for increasing our sense of hunger, among other important functions. Subsequently, some data has indicated that LGAE patients also then lose weight as a result. Stomach cells in the fundus produce most of the body’s ghrelin, though the small intestine, pancreas, and brain contribute as well.

So far, though, the clinical research supporting LGAE as a bariatric treatment is limited, with studies often including only a handful of patients at a time. This new research, led by scientists at the Imperial College London in the UK, appears to be the largest test of LGAE to date.

The randomised, blinded, placebo-controlled trial, which is expected to cost around $US1.5 ($2) million USD, will recruit 76 patients with a body mass index between 35 and 50. All of the patients will get the procedure, but only half will actually have their artery blocked, while the other half will simply have saline solution passed through it. The trial just began this month, according to the Daily Mail, and is meant to run for a year.

“There is a real need to expand the weight loss treatments currently on offer for patients, especially those who don’t want to go down a surgical route,” project researcher Prashant Patel said in a statement last month from the university. “LGAE has been shown to be a promising minimally invasive treatment but there’s not yet been enough research for us to say how effective it might be. Our research will help us to answer this question and see if it could be a viable treatment for people living with obesity.”

Reviews of the data on LGAE have found that patients lose somewhere between 8% and 10% of their body weight. That’s a rate above most pharmaceutical treatments for obesity, though below most other types of bariatric surgery. Those procedures require the permanent restructuring of the stomach or intestines, however, and relatively few people living with obesity opt for them even when eligible. LGAE on the other hand is minimally invasive and can be done as an outpatient procedure with local anesthetic, according to the Imperial College London researchers, and it may cost less than $US2,000 ($2,838) to perform (by contrast, the average bariatric surgery can run $US14,000 ($19,866) to $US23,000 ($32,637)). Side-effects of LGAE also appear to be mostly mild and short-lasting, but can include nausea, stomach discomfort, and vomiting.

There are still many questions about LGAE that this trial may help answer, though. There is debate over the role that ghrelin actually plays in contributing to most cases of obesity, and some researchers wonder whether the effects of LGAE on ghrelin production and weight loss will be sustained over time. In 2019, a small trial in the U.S. did find LGAE patients had maintained their weight loss a year later.

LGAE isn’t the only newfangled weight loss treatment out there. Earlier this year, Novo Nordisk won approval in the U.S. for its obesity at-home treatment Wegovy — a injectable, higher dose version of semaglutide, a synthetic analogue of the hormone GLP-1 that’s already used to help manage type 2 diabetes. Wegovy has shown even larger weight loss results than LGAE, but is highly priced at around $US1,600 ($2,270) a month with limited insurance coverage so far (nor is Wegovy universally seen as a good thing). The drug has since won approval in Canada and likely the EU very soon, through supply issues mean that the drug will remain hard to get anywhere until next year.