That the Arctic is a hot mess due to climate change is well-established at this point. But it’s always nice to have a reminder of just how out of whack things are getting, isn’t it?

A new report provides just such a reminder, showing that lightning is significantly increasing at the highest latitudes, a region more familiar with the Northern Lights than storms lighting up the skies. The trend was particularly acute in 2021, which saw 91% more lightning in the far northern Arctic than in the previous nine years combined.

The shocking findings come courtesy of Vaisala, a meteorology firm with the best lightning detection network on Earth, which released its annual lightning report earlier this week. The whole report is honestly fascinating because, well, it’s about lightning. But the Arctic findings are a sobering reminder of the radical changes happening in the region.

Lightning — or more specifically, the storms that can spawn it — requires warm, moist air and atmospheric instability. That’s usually in short supply in a region dominated by ice and snow. Or, more accurately, formerly dominated by ice and snow. Rising temperatures have helped usher in a new Arctic. Sea ice is disappearing, opening up the tap for more lightning-causing storms.

“Climate is changing faster in the Arctic than elsewhere on the planet,” Chris Vagasky, the lightning applications manager at Vaisala, said in an email. “Lightning indicates very specific changes that are occurring – specifically intrusions of warm, moist air into the region.”

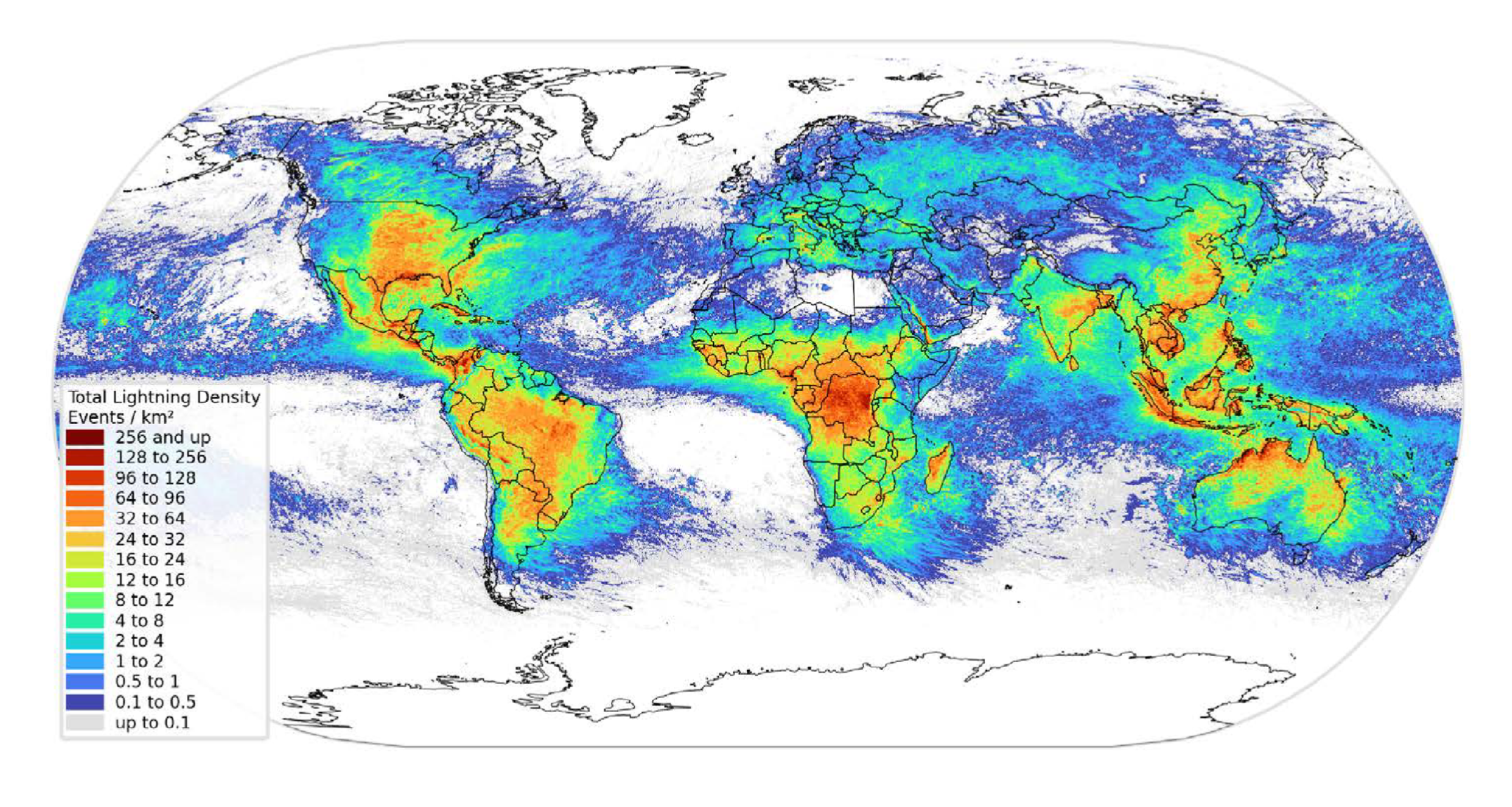

The report breaks down what’s going on at different latitudes above the Arctic Circle, which sits at 65 degrees North. Vaisala’s lightning network uses sensors placed around the world to, in Vagasky’s words, “‘listen’ for the unique signatures produced by lightning” in the form of very low frequency electromagnetic waves associated with the phenomenon. That allows it to detect lightning in far-off places, from the tropics to the Arctic.

The findings show that lightning has stayed relatively constant in the lower reaches of the Arctic. Last year, the region around the Arctic Circle saw 1.9 million lightning detections, roughly in line with where things stood in 2012. But something weird is happening above 80 degrees North.

There, Vaisala’s network has detected a radical uptick in lightning activity. The region saw 7,278 lightning detections in 2021. That’s a relatively small number, especially compared to much lower latitudes — Texas alone, for example, saw nearly 42 million bolts of lightning in 2021 — but it’s a sharp rise compared to the previous decade and easily set a record. Most of that activity happened over a three-day period in late July and early August.

“What we saw was a series of low pressure systems exiting northern Siberia and crossing the Arctic Ocean – that’s the source of lift,” Vagasky said. “High temperatures were approaching or even exceeding 80°F [27 degrees Celsius] on the Arctic coast and very high humidity was funelling northward from central Russia. This created the kind of atmospheric instability typically seen over the Great Plains of the United States during severe weather outbreaks.”

At 85 degrees North, Vaisala detected lightning 634 times. That’s also a record, for a region that’s more accustomed to seeing no lightning at all in some years.

To understand just how weird all this is, consider that the area above 80 degrees North is a stronghold for sea ice. Look at a map of where ice has usually held tight over the past 30 years, and it’s this exact location. But rising land and ocean temperatures eating away at icepack have opened the door for more freak storms and lightning.

Last year’s record amount of lightning is part of a larger trend. In 2019, lightning struck near the North Pole, an event that the National Weather Service said, in typically understated terms, was “certainly unusual.” Research published last year also shows that Arctic is seeing more lightning crisscross the sky, and that it’s likely due to climate change. Yet another study found that lightning-caused wildfires are also increasing. In a region that already has enough to worry about when it comes to climate change, lightning is yet another concern to toss on the pile.