This week, European authorities struck a massive blow to the digital data-mining industrial complex with a new ruling stating that, quite simply, most of those annoying cookie alert banners that sites were forced to onboard en masse after GDPR was passed haven’t… actually been compliant with GDPR. Sorry.

The ruling, announced on Wednesday by Belgium’s Data Protection Authority, comes at the tail-end of a years-long investigation into one of the biggest advertising trade groups in EU, Interactive Advertising Bureau Europe (or IAB Europe, for short). In 2019, about a year after GDPR rolled out, the Data Protection Authority reports it started getting a stream of complaints against the IAB for “breaching various provisions of the GDPR” and countless people’s privacy with the technical standards it created to govern those consent pop-ups.

Now, three years later, it looks like those tips were right; the Authority fined IAB Europe $US280,000 ($388,696), ordered the group to appoint a data protection officer, and gave a two-month deadline to get its tech into compliance. Any data that the group collected from this illicit tech also needs to be deleted.

The ruling is great news for privacy buffs that have been calling out those ugly, oftentimes downright manipulative cookie pop-ups from the get-go, but it’s also not necessarily a surprise. In an apparent attempt to get ahead of the bad press, IAB Europe issued a statement last November that the upcoming ruling would “apparently identify infringements of the GDPR by IAB Europe,” but that those infringements would be fixable, and those cookie consent banners would keep on chugging within months of the Belgium ruling.

But that statement came in 2021. For those who work on the so-called “sell-side” of the digital ad industry — tech operators who work hand-in-hand with digital media outlets and other sites across the web — this decision was inevitable. I spoke with three of these industry experts, all of whom asked to not be cited by name for fear of professional retribution thanks to the sway IAB holds over the industry.

While the ruling showed that GDPR is very much still in effect, it doesn’t do a lot to explain how blatant some of these infringements were, or how loudly critics inside the industry had been raising red flags. Simply put, when the GDPR asked the adtech industry to get consent from users before tracking them, the IAB responded with a set of guidelines with loopholes large enough that data could still get through, anyway, without consent. And now that these practices are out in the public, nobody seems sure how to make them stop.

But to really explain how IAB Europe fell afoul of GDPR is complicated, even by adtech’s already impossibly confusing standards. So instead, I’m going to explain it using an analogy that pretty much everyone can understand: a bad date.

I know it sounds wild to compare a sweeping piece of European tech legislation to someone’s nightmare Tinder experience, but both are centered around the same thing: consent. That’s why regulatory types will often champion GDPR as the gold standard of privacy laws — while laws like CPRA in the U.S. allow people to claw back their data from the companies after they’ve mined it, the California law doesn’t change the fact that this mining happened in the first place, regardless of whether users wanted it to happen or not. GDPR, on the other hand, mandates that sites obtain users’ consent to track them before that tracking happens, the same way a decent date would (hopefully) ask to make out before slobbering all over you at the bar.

On paper, consent is just an agreement between two people (or a person and a website). But your Tinder date might have different thoughts about what “an agreement” means than you do. If they ask to do some slobbering and you brush it off with a laugh, they might take that lack of “no” as a “yes.” They might also ply you with drinks or intimidate you into getting out the “yes” they’re looking for, which is — and I can’t stress this enough — not consent. And even if you can’t articulate what consent looks like in the moment, you probably know in your gut what it feels like: Consent is a “yes” that’s unambiguous and freely given.

That’s exactly how GDPR defines the term, too. In order for a site to track you, Article 4 of the regulation notes that it needs to obtain a “freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous indication of the data subject’s wishes by which he or she, by a statement or by a clear affirmative action, signifies agreement to the processing of personal data relating to him or her.” And no pre-ticking consent boxes, either, buster.

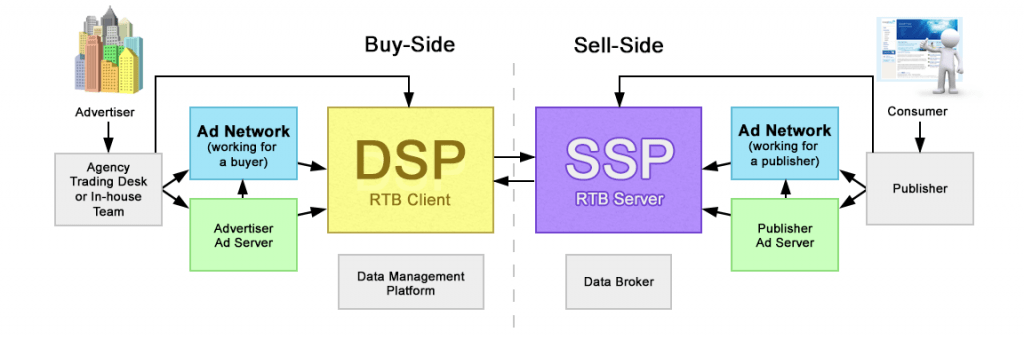

But that little tick is, quite literally, just a tiny pile of snow at the top of a massive iceberg. On every page you’re visiting, there could be a few, or dozens, or even hundreds of tiny tech companies working together to take whatever data gets exposed through the webpage you’re visiting into some kind of targeted ad. By the time that annoying ad for some ugly t-shirt pops up on a blog you’re reading, there have already been countless algorithmic bidding wars on that ad space — the spot on the page where an ad appears — that are each their own Olympic feats of Big Tech gymnastics. If this all wasn’t so invasive and upsetting, it would almost be kind of impressive.

In other words, the way web tracking works isn’t really like a single guy being a sleaze at the bar; it’s more like a conga line of sleazes. And in order to get your consent, this Tinder guy (let’s call him ‘Devin’) that you just met is being legally required to go with you down the row and, one by one, consent to smooching up on each of these other guys before a single smooch could ever happen.

You might be thinking, “Geez, if I was the Devin in this scenario, I’d just give up on getting consent for all my weird friends, and just try to be sleazy on someone with lower standards.” And you’re not alone! In the leadup to GDPR going into effect, countless recipe blogs, news outlets, and just regular-old personal blogs looked at this seemingly impossible standard EU regulators were now mandating from them and just… panicked. Who could blame them?

“The thing that almost every publisher was worried about was that they were going to do all this work and get hit by regulators anyway,” said one adtech engineer who also asked to remain anonymous out of fear of retribution from the IAB. “The language of the law didn’t get clear about how the technical method was supposed to work, what you could or couldn’t block off, what level of ID you were allowed to ask a user for, etc.”

Rather than try to parse a law that was, as he put it, “both not specific enough and too specific,” to actually be effective, some publishers just left. In GDPR’s immediate aftermath, more than 1,000 news sites were suddenly unavailable trying to visit from the EU, with the bulk being smaller, local outlets, according to a list that one researcher compiled at the time. That’s not a coincidence; while the New York Timeses and Washington Posts could afford a legal team and tech setup to stay put without being threatened with GDPR’s massive fines, local outlets were already struggling.

But this still left countless websites active in the EU that needed consent from their visitors once GDPR came into force. Enter the IAB. Because a lot of adtech is pretty much unregulated, the massive influential trade group has come to be accepted as the one to set the guidelines for advertisers, publishers, and everyone else to follow in order to keep them from running afoul of privacy laws. Both the IAB and its European wing are really, really serious about lobbying, which means that — ideally — the organisation would know exactly what makes these laws tick, and how the industry could accommodate them.

So, naturally, IAB Europe was responsible for coming up with the standards for websites that wanted to obtain user consent without effectively breaking their site in the process. And then, according to the industry experts I spoke with, they kept waiting. In April 2018 — literally a month before GDPR was set to come into effect — IAB Europe debuted its new standards: the so-called “GDPR Transparency and Consent Framework” (or TCF) that websites were told would collect consent in a comprehensive, standardised way, while also funelling that consent back to the third-party partners each site works with.

This framework, to be blunt, looked like a hot mess. There were a few glaring issues critics pointed right off the bat, but one of the biggest was that the framework encouraged sites to bundle all their requests for consent — from every third party they work with — under a single “accept all” button, without the need to actually disclose every one of the many, many partners that were hiding under that button.

In other words, these guidelines suggested that Devin just hide all his buddies inside a trench coat, with the implicit understanding that if you agreed to smooch him, you’d agree to smooch all of them, too. But that’s not how consent works IRL, and that’s not how consent is supposed to work under GDPR.

So, when these new TCF specs were dropped in their laps with a month to go before European laws changed in major ways, website operators were faced with a pretty crummy choice: go through the expensive and mind-numbing legal process of bringing their site to compliance on their own, or going with what the IAB was presenting.

As one person in charge of advertising revenue at a major publication put it, IAB’s standards seemed bent on adhering to the letter of the law while ignoring the spirit of the law. Another industry expert thought the TCF standards seemed purposefully complicated to allow publishers to skirt regulation.

But without other options, publishers — begrudgingly or otherwise — decided to follow the TCF standards anyway. As one expert explained, the implicit understanding was that if anyone would take the fall for shoddy privacy compliance, it would be the IAB, and not them. And so far, at least, that’s exactly what’s happened. While the Data Protection Authority fined IAB Europe, it has gone after publishers themselves, even though they’re also breaking GDPR by using the TCF standards.

To follow the framework, publishers were required to onboard another third-party piece of ad software called a “consent management platform,” or CMP, that would be responsible for collecting consent from users and beaming it where it needed to go. Those CMPs — and there are dozens of different ones — need to be registered with the IAB for “compliance” purposes, which also means forking over a roughly $US1,700 ($2,360) fee upfront, and again each year they’re on the list.

These CMPs are the ones responsible for plopping the dreaded cookie banner on the site. Behind the scenes, when you press “yes” or “no” on a site’s request to track you, that choice gets stored in the form of a “consent string” on your browser. Unless you clear your browser cache (which, let’s be honest, you should probably do), that webpage will load up that string every time you visit and pass it on to any third parties involved with serving an ad on the site — you know, that aforementioned chain of sleazy dudes.

Pretty quickly, though, it became clear that the rules laid out by TCF weren’t going to cut it, and the cookie banners created in its wake were blatantly violating some of GDPR’s core rules in all sorts of shady ways. Some would share people’s consent preferences on a single site with every company that was partnered with the IAB, while others would leave site visitors with the option to accept cookies, but not the option to reject them. Others would just not work at all.

What eventually brought Google onboard was the IAB’s new and improved TCF 2.0, which debuted about a year and a half after GDPR rolled out. We won’t go into every change (you can read about those here), but in a nutshell: This new framework promised more power to publishers, more privacy to end-users, and less of a legal shitshow overall. But when digital advertising is a field that’s flush with hundreds of billions of dollars per year and not nearly enough legal oversight, bad actors are going to be bad. Dark patterns continued to be dark even with the update, and middlemen further down the daisy chain from the CMP started offering alternatives meant to bypass these cookie banners entirely, meaning that the need for consent — which, again, is the core tenant of GDPR — would no longer be part of the equation.

In some absolutely cursed scenarios, CMPs began forging consent signals from end-users — literally turning their requests not to be tracked into a “yes, please track me” — with nobody, even the IAB, checking in initially. Even after the trade group started auditing the vendors it worked with last fall, researchers outside the adtech sphere found that consent fraud was still very much happening, with seemingly no easy way to get bad actors to stop.

As one adtech executive speaking about the issue to Digiday put it, “not many businesses are incentivized to completely clamp down on it because everyone’s motivations are commercial. No one gets a bonus for being legally compliant, they get a bonus for hitting their numbers. It’s a frustration for any exchange that’s following the rules because it puts them at a massive commercial disadvantage. We’re sticking to the IAB’s rules, but it is hurting us to do so.”

You could say their dilemma is a microcosm of regulators’ attempts — in the EU and abroad — to get the digital data industrial complex under control. When regulators set standards that are too tough for anyone to practically follow, talking heads within the industry create their own response that ticks every legal box while also enabling anyone creative enough to continue with business as usual anyway. And when publishers are literally stuck between “too easy to cheat,” and “impossible to adhere to,” which one do you think they’ll choose?

The full ruling against IAB Europe doesn’t address the bad behaviour of these downstream parties. Instead, it’s going after IAB Europe’s awful standards, and its consent strings, specifically. “Contrary to IAB Europe’s claims, the Litigation Chamber of the BE DPA found that IAB Europe is acting as a data controller with respect to the registration of individual users’ consent signal, objections and preferences by means of a unique Transparency and Consent (TC) String, which is linked to an identifiable user,” the Authority wrote in a statement about the new ruling. “This means that IAB Europe can be held responsible for possible violations of the GDPR.”

Based on this, the Authority was finally able to go after the IAB directly for what it describes as a flurry of infractions. For starters, the ruling alleges that IAB Europe “failed to establish any sort of legal basis for the processing of these consent strings under GDPR,” and failed to keep that data “confidential,” by GDPR standards, once it was collected. On top of that, the new ruling agrees with the same complaints a lot of us have had about those cookie pop-ups for years: They’re too vague, too hard to opt-out of, and just clearly don’t do what they’re promised to do.

“The information provided to users through the CMP interface is too generic and vague to allow users to understand the nature and scope of the processing, especially given the complexity of the TCF,” the Authority wrote, noting how “difficult” this makes it for any user to actually have the control over their data that GDPR warrants,

So what comes next? Well right now, nobody seems to know. IAB Europe put out a terse statement on the ruling that noted how the group “[looks] forward to working with [the Belgian Data Privacy Authority] on an action plan to be executed within the prescribed six months that will ensure the TCF’s continuing utility in the market.”

“As previously communicated, it has always been our intention to submit the Framework for approval as a GDPR transnational Code of Conduct,” the group wrote. “Today’s decision would appear to clear the way for work on that to begin.” Well, good luck with that. In the meantime, we’re stuck with essential parts of the entire ad-serving market in the EU being rendered… entirely illegal. At least for now.

It’s impossible to say what’s going to come next, but given the adtech industry’s lengthy track record of sweeping bad actors under the rug instead of stopping them cold, and with those bad actors facing the huge financial incentive to keep being bad, I think it’s safe to say that’s what they’ll keep doing. When a major part of the online economy is just a big race to the bottom, you just need to pray that lawmakers get there first.