Using a microphone, a laser, and some crafty mathematics, a team of scientists has measured the speed of sound on Mars, in what is a scientific first and another cool finding made possible by NASA’s Perseverance rover.

There’s lots to love about the Perseverance mission, but one of my favourite aspects of the rover is that it’s capable of recording audio. Early last year, and for the first time ever, we actually got to hear sounds on Mars, both natural and synthetic. Using its SuperCam microphone, the rover recorded blowing Martian winds, clicks from its rock-scanning laser, and crunching sounds made by its rolling wheels.

That Perseverance’s microphone would detect these sounds wasn’t a certainty, given the achingly thin atmosphere on the Red Planet. Sound needs a medium to propagate, and Mars, with a paltry atmospheric pressure of 0.095 pounds per square inch (psi) at ground level, doesn’t offer much to work with. By comparison, Earth’s sea level atmospheric pressure is around 14.7 psi.

But there they were — discernible noises picked up by Percy’s microphone in Jezero crater. With sounds clearly audible on Mars, Baptiste Chide from Los Alamos National Lab in Los Angeles and colleagues were able to measure the speed of sound on Mars. The scientists recently presented their findings at the 53rd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, held from March 7-11 in Texas.

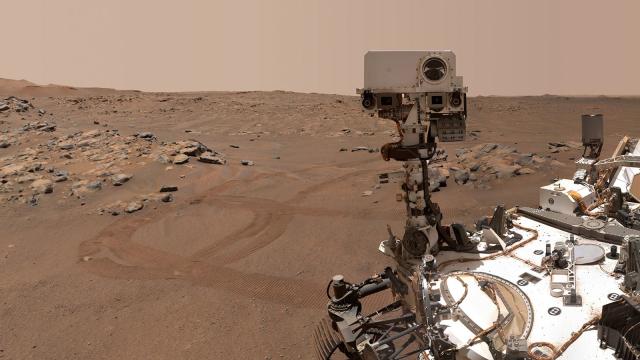

The team leveraged Perseverance’s SuperCam experiment, which zaps rocks with lasers to study Martian geology and sits at the head of the rover’s mast some 6.9 feet (2.1 meters) above the Martian surface. The team took measurements from 150 laser shots taken at five distinct locations, while also tracking local weather conditions.

By measuring the time it took the staccato-like clicking sounds to reach the SuperCam microphone, they were able to establish the speed of sound on Mars, to a precision of plus-minus 0.51%. They found that sound on Mars travels at 239.88 m per second (240 meters per second), which is significantly slower than the sound of speed on Earth at 339.85 m per second (340 m/s).

And in an observation that matched prior predictions, the speed of sounds below 240 hertz fell to 754 feet per second (230 m/s). That doesn’t happen on Earth, as sounds within the audible bandwidth (20 Hz to 20 kHz) travel at a constant speed. The “Mars idiosyncrasy,” as the scientists call it, has to do with the “unique properties of the carbon dioxide molecules at low pressure,” which makes the Martian atmosphere the only one in the solar system to experience “a change in speed of sound right in the middle of the audible bandwidth,” as the scientists wrote. The reason for this is that sounds above 240 Hz don’t have time to relax their energy, according to the scientists.

The scientists go on to say that this acoustic effect “may induce a unique listening experience on Mars with an early arrival of high-pitched sounds compared to bass.”

Unique is right! Lots of acoustic information exists below 240 Hz, including the low end of music and the lowermost registers of the human voice (typically for males). Music on Mars would sound completely messed up (particularly with increased distance), with the middle and high frequencies reaching the listener slightly before the low frequency sounds, such as the lower registers of the bass guitar and kick drum. Add another effect of carbon dioxide, the attenuating, or dampening, of higher frequencies, and the acoustic experience gets even weirder.

As a neat aside, the technique used to measure the speed of sound can also be used to measure the local temperature. So in addition to Percy’s Mars Environmental Dynamics Analyser (MEDA) instrument, the team has a new thermometer at its disposal. Looking ahead, Chide and his colleagues will run more tests to measure the speed of sound at different times of the day and during different Martian seasons.