The night of Feb. 27, Austrian historian Sebastian Majstorovic couldn’t sleep. Three days earlier, Russia had invaded Ukraine, a country Vladimir Putin believes lays no claim to independent statehood or a distinct identity.

Ukraine’s cultural institutions hold mountains of evidence of proving Putin wrong, Majstorovic thought, but the war put this valuable knowledge and history at risk of being lost forever. While he couldn’t physically travel to Ukraine to protect museums or libraries, there was something he could do from his computer: make copies of the websites and online collections of those places.

Join me for a virtual data rescue session focused on music collections at cultural heritage institutions in Ukraine which may be at risk during the attack by Russia. For more info & to participate go to https://t.co/LPLU6lMAnO (@achdotorg @aseeestudies) Share widely!

— Anna Kijas (@anna_kijas) February 27, 2022

This way, there would be backups of the Ukrainian servers hosting the digital artifacts if they were destroyed during the invasion or their displaced owners became unable to pay. Without such backups, the content would be lost.

The black holes created by the destruction of cultural heritage are “irreversible,” Majstorovic, who works at the Austrian Centre for Digital Humanities and Cultural Heritage, told Gizmodo in a phone interview from Vienna. Launching a data rescue session, which some had proposed doing in a few days on social media, couldn’t wait. He started that night.

“It might be too late,” he said. “Who knows if the internet [will] still be working?”

Rattled, he got up and started using a suite of tools from the site Webrecorder to archive some cultural heritage sites from Ukraine himself, taking snapshots of a website’s content and downloading a full copy for preservation. He worked the entire night. The next morning, he asked his Twitter followers to round up digital Ukrainian collections they wanted to preserve using a Google Form. He quickly joined forces with Anna Kijas, head of the Lilly Music Library at Tufts University, and Quinn Dombrowski, an academic technology specialist from Stanford University, who also felt the need to act fast before the sites and digital collections were lost to the war.

Together, the three launched the “Saving Ukrainian Cultural Heritage Online” initiative, or SUCHO, on March 2. SUCHO works to create a digital backup of Ukrainian cultural heritage websites from museums, libraries, and public archives and their digital offerings, such as 3D collections and activities for children.

To date, SUCHO has gathered almost 20 terabytes of data and preserved more than 2,700 partial or complete websites. Their work is a race against time. More than 15% of the 3,000 websites that have been submitted by the public for backup are already offline, according to the group’s organisers. They track the status of the websites but don’t know why certain sites go offline. Some sites that disappeared were already backed up. Some were not.

One example of a website they’ve saved is the official State Archive of Kharkiv, a government website. On March 2 and 3, the group crawled and downloaded the entire website, which is 109 gigabytes. “It was a really close call,” SUCHO’s organisers said, explaining that the State Archive of Kharkiv went offline that same afternoon and hasn’t come back online since.

As of the publication of this article, the website is still down. On March 10, Anatolii Khromov, head of the State Archival Service of Ukraine, shared that the building of the State Archive of Kharkiv had been damaged by Russian bombing. The entire site is still accessible thanks to SUCHO’s members, who recorded its contents using Replay Web, one of Webrecorder’s tools.

The State Archive of Kharkiv is far from the only cultural heritage institution that has been damaged. The Ukrainian government keeps a public website on the war crimes committed by Russians during the war, including damage to museums, libraries, works of art, monuments, and ancient buildings. So far, 123 crimes have been reported.

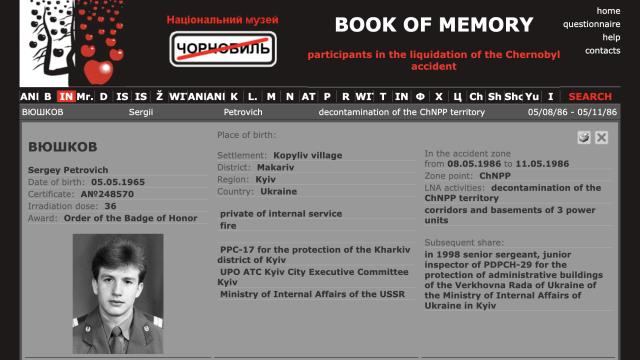

Other websites archived by the group include the “Book of Memory,” a repository which documents the names and photos of more than 5,000 people who participated in the disaster management operation for the Chernobyl nuclear accident in 1986 from the National Chernobyl Museum. SUCHO has also backed up the site of Ukrainian Centre for Cultural Studies, a virtual museum of cultural heritage with digital exhibits about the country’s traditional songs, ceramics, weaving patterns, and more.

Both of these websites are still online, but their future is secure should their servers get damaged.

Mobilizing an international coalition of online volunteers

SUCHO’s founders don’t work alone — they are supported by an international coalition of online volunteers of more than 1,300 that archive websites and content day and night. The group has also received emergency funding grants from the Association for Computers and the Humanities and the European Association for Digital Humanities, among others. Amazon Web Services is also hosting their server infrastructure free of charge. Organisers wanted to make sure the project’s servers were distributed and replicated around the globe.

Volunteers hail from a wide range of groups. Some are international employees of museums, libraries, and technology companies, others are people who have roots in the region. They can work on a variety of different tasks within SUCHO. Some work on full-site archiving using Webrecorder’s Browsertrix tool, while others who can read Russian or Ukrainian run quality control for the captured sites to ensure the archivists didn’t miss anything major. Another group is focused on situation monitoring in Ukraine, i.e. keeping track of attack and air raid alerts, to help SUCHO prioritise which websites to archive.

Yuliya Ilchuk, an assistant professor of Slavic languages and literatures at Stanford University who is Ukrainian, supports SUCHO with her research funds. She was initially approached by Dombrowski, her colleague at Stanford, about the initiative. In that moment, she told Gizmodo, Ilchuk realised that cultural heritage didn’t only include material objects but also data, and got on board. Ilchuk has been affected by the war on a personal level. Originally from the Donbas region in eastern Ukraine, which has been partially occupied by Russian-backed separatists since 2014, she came to the U.S. in 1999 to pursue an academic career. However, her entire family is back in her home country.

Besides providing funding, the professor helps connect SUCHO to people in Ukraine who can help the group identify which collections to archive. It’s not easy, she said, because people in her home country are worried about trying to survive.

Volunteers don’t have to have technical expertise to contribute to SUCHO, which now has a waitlist. The team has been holding Zoom workshops to show people how to install Webrecorder’s software on their computer. Even kids have helped. On Wednesday, Dombrowski held an event at their children’s elementary school to show them how to archive a website using Browsertrix.

Anna Rakityanskaya, librarian for the Russian and Belarusian collections at Harvard University, is one of SUCHO’s “non-techie” volunteers, contributing to the initiative with her language skills and professional cataloging experience. While she doesn’t personally archive any websites, she provides descriptions to what’s been archived, a task that allows her to study the content in detail. She said that the website that has most affected her on an emotional level was one from the Oles Honchar Kherson Regional Universal Scientific Library located in the southern city of Kherson. The city was captured during the first week of the Russian invasion.

“What touched me the most were the pages that had to do with community outreach, because they show pre-war photographs of people engaged in some leisure activities like discussing books… knitting together, teaching crafts to children,” the librarian told Gizmodo in an email.

“When I look at these photographs, I can’t help thinking where all these people could be now,” she said.

On the technical side, the initiative has enlisted the direct help of the Webrecorder project, which is responding to its needs and modifying its tools in real-time.

Ilya Kreymer, founder of Webrecorder, was invited to join SUCHO by Majstorovic, the project co-organiser. Kreymer said he was amazed and inspired at how people around the world had come together to start a community-driven archiving effort on such short notice. The extra traffic to Kreymer’s site has not been without its challenges. He runs Webrecorder on his own and hires additional help part-time, so he has been overwhelmed at times because he can’t respond to every bug report or question right away.

“It’s a little bit scary as I was hoping to have a bit more time to test the tools before folks start using them in production, but sometimes things just need to be done urgently, such as when there is a war going on and [we] need to move quickly to save these websites in case they get take offline,” he said.

In addition to responding to problems, Kreymer also accelerated the deployment of the Browsertrix Cloud system, which provides a simple user interface for its automated browser-based crawler.

SUCHO even has supporters in the art world. Brendan Ciecko, CEO and founder of the engagement platform Cuseum, commissioned a series of artwork from Ukrainian artists — including the pieces featured in this article — to help promote SUCHO and commemorate the efforts of those involved.

“The best possible outcome for us is for none of this to be needed.”

Although it may seem counterintuitive, Dombrowski said “the best possible outcome for us would be for none of this to be needed,” that is, for all the servers located in Ukraine to be uncompromised and all the websites to operate normally as soon as the war ends.

Dombrowski said that the SUCHO initiative is committed to working with Ukrainian experts and government officials to help them rebuild their websites using the archives. They emphasised that the archives belong to the people of Ukraine and their cultural institutions. The project plans to transfer the data to the appropriate entity in Ukraine when the time comes.

The group is beginning to think about its next steps, including curation of the websites collected and large-scale identification of the information they contain. The task will require the help of more archivists, librarians, and engineers.

On another level, the group is also trying to figure out how to transfer, or transform, the technical infrastructure it’s created so that it can be used by other institutions internationally to preserve their digital cultural heritage data. Majstorovic, the historian, said the idea is to save the data before disaster strikes so that rescue missions like SUCHO aren’t necessary. The danger isn’t limited to when countries are at war. Digital culture heritage data can also be in danger when there’s a flood or another natural disaster.

Unlike big tech companies, Majstorovic said, cultural institutions often don’t have the funding or the means to back up all the things they’ve digitised. He added that SUCHO was already talking about the issue with UNESCO, the International Council of Museums, the Smithsonian, national libraries, and a number of European research consortia. The entities are eager to learn from SUCHO, Majstorovic said.

Majstorovic wants the public to realise that cultural heritage is precious and fragile. It’s not a luxury, he stressed, but an “absolute necessity.” Dombrowski, meanwhile, says that the SUCHO project demonstrates that anyone can help if they have the determination to work on something, even if it’s unfamiliar.

“Regular people can actually do something to make a difference, even if it’s, you know, relating to a conflict that’s far away,” Dombrowski said. They added: “Sometimes what it takes is closing on the news site and, you know, finding a group that’s actively doing something to do it.”