“I just wish I could save them all,” my virtual reality police officer avatar says as he gazes upon a young woman’s abandoned corpse lying beside a back-alley dumpster. My VR cop partner offers a limp gesture of condolence but doesn’t sugarcoat the reality: My decision got this woman killed.

I made the incorrect, deadly choice during an hour-long demo of Axon’s VR offerings earlier this month. The company, which created the Taser and now claims the lion’s share of the cop body camera market, believes the techniques practiced in these VR worlds can lead to improved critical thinking, de-escalation skills, and, eventually, decreased violence. I was grappling with the consequences of my decision in the Virtual Reality Simulator Training’s “Community Engagement” mode, which uses scripted videos of complicated scenarios cops might have to respond to in the real word.

“Axon’s VR Simulator Training is truly a new era in law enforcement training,” the company’s VP of Immersive Technologies Chris Chin told me.

Experts on policing and privacy who spoke with Gizmodo did not share Chin’s rosy outlook. They expressed concerns that Axon’s bite-sized approach to VR training would limit any empathy police officers could build. Others worried bias in the VR narratives would create blind spots around truly understanding a suspect’s perspective. Still others said Axon’s tech-focused approach would do nothing to reduce the overall number of times police interacted with vulnerable people — an expensive, unnecessary solution.

“When all you’ve got is a techno hammer, everything looks like techno nail,” Santa Clara University Associate Professor Erick Ramire said.

Axon said it worked with law enforcement professionals, mental health counselors, clinicians, academics, and other experts to create the narratives that populate its educational simulator. The company did not include one notable group: victims of police violence.

When I asked a corporal in the Delaware force if he thought it was strange that Axon didn’t consult police brutality victims, he paused, eventually saying, “That’s a good question.”

During my demo, I was strapped on HTC’s Vive Focus 3 headset and opted to experience a drug-related incident. A few menu screens pass by, and suddenly you find yourself plunged into in a Gotham-esque, grungy alley speaking to a woman struggling with withdrawal who just had her purse stolen by her drug dealer. After a brief, uncomfortable conversation where you try to convince the woman to spill the beans on her dealer’s name, your partner turns to you and asks you what you should do with her. Much like a role-playing game, three text options appear on the bottom of your point of view reading: Let her off with a warning, take her into custody, or investigate further. I let out a nervous laugh as I realised a conference room full of Axon employees were carefully watching my choice. I look through the options several times then eventually opted for the warning. As I’d soon learn in graphic fashion, I made the “wrong” choice.

What Axon really wanted to show me were two new VR trainings: a firing range and an interactive domestic abuse scenario. The former launches this week, the latter later this year. The company started releasing content for its Community Engagement simulator last year and says it is continually creating new scenarios and releasing new content each month, eight modules in all. They involve responses related to autism, suicidal ideation, Veteran Post-Traumatic Stress Injury, and Peer Intervention. The event options are laid out on a menu screen like the levels of an early 2000s platformer game.

Rather than presenting you with a Super Mario style “Game Over” screen, the simulator rewinds to the previous night and coaxes you into selecting the “right” answer, which was to investigate further. Through conversation, you eventually convince the woman to check herself into a rehabilitation facility and even give her your personal phone number (supposedly not in a weird way) to keep tabs on her. This time, the scene fast forwards months later and shows you, the officer randomly meeting up with the woman jovially jogging down the street. She’s turned a full 180 and pieced her life back together. She expresses her gratitude to you for saving her life.

“It directly supports Axon’s mission to protect life by giving law enforcement officers the ability to work through situations they see in their communities daily via VR and help create better outcomes for everyone,” Chin said.

Officers using the simulator can opt to work through scenarios involving individuals with autism or schizophrenia. In an attempt to encourage empathy, users will occasionally flip perspectives and view the world through the victim or suspect’s point of view. In one bizarre case, I even viewed the world through a baby’s POV. Axon told me users viewing the world through the eyes of people with schizophrenia will actually hear faint voices crawling through their headset.

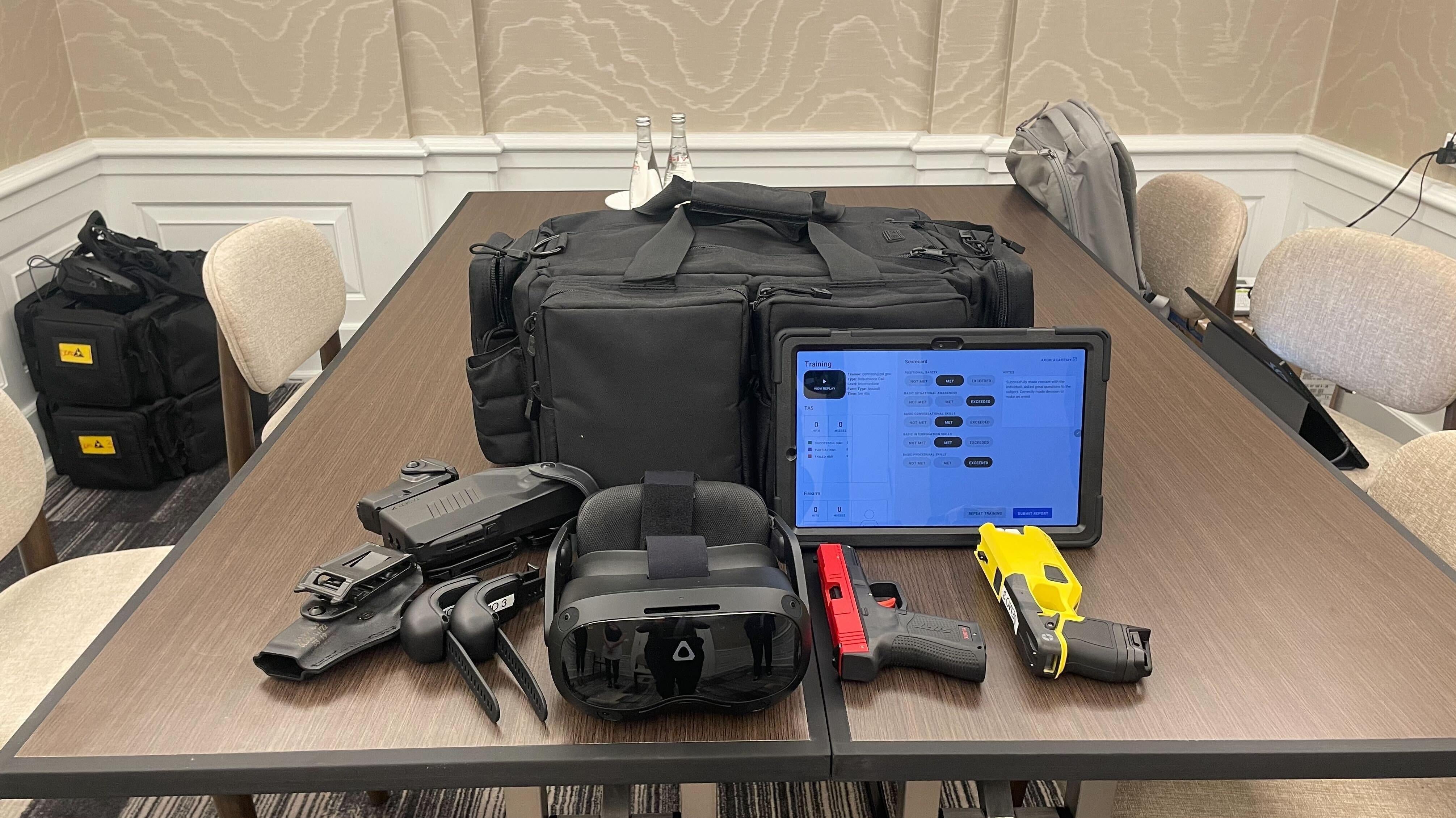

The simulator’s hardware package consists of a Vive Focus 3 headset, an accurately modelled and weighted mock Glock handgun, a mock Taser, a tablet, and two computer mouse-looking VIVE Wrist Trackers. These newly created trackers are what lets participants realistically wield their weapons in VR. The entire system fits in a black travel bag that’s relatively light and could easily be mistaken for overhead luggage on an airline. During the firing range training, I cycled between blasting targets with a Taser and letting the lead out with a Glock while an instructor observed and scored me with a tablet. I was told my shooting could “use improvement.”

Axon hopes its VR firing range will increase officers’ comfort levels with Tasers, which, the company believes, could decrease the use of more lethal firearms in real-world environments. To that end, Axon designed its VR firing range so that officers can use their own personal Tasers in VR. They simply need to swap out their cartridge for the Taser equivalent of a blank round, and they’re ready to shoot.

Law enforcement agencies interested in Axon’s package and related content on Its “Axon Academy” platform will have to dish out $US3,790 ($5,261) to purchase the kit alone. Axon says agencies can also to bundle the kit with the company’s other products, which can rack up a bill anywhere from $US17.50 ($24) to $US249 ($346) per user per month.

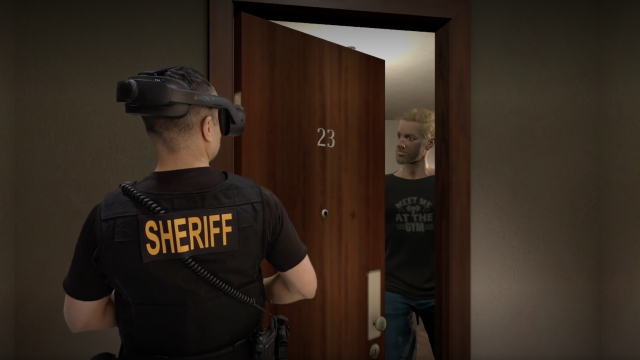

While Axon’s previous VR training released last year used live film with real actors, the new interactive domestic violence scenario I demoed features avatars that look like video game characters. In this mode, an instructor using a taser can change specific details of a scenario on the fly, adjusting the way characters might look or talk and boosting the level of tension up for down. Unlike previous versions of Axon’s simulators where users passively view the world, the new version lets you move around and interact with objects (I knocked on a door, for example) which creates an inherently more engaging and present experience.

Unfortunately, this more interesting demo was cut abruptly short. Axon employees told me they are still tinkering with the scenarios and aren’t planning to release this more interactive domestic violence simulation until the second half of this year.

Civil liberty experts express concerns over potential narrative bias

As someone who grew up shooting guns in the Southeast Texas brush, I found myself surprised to be convinced by Axon’s replication of firearm shooting in VR. The virtual firing range truly felt like there was empty space around you, the model Glock felt familiar in the palm, and the tactile roar of recoil and explosive crackling left me quickly feeling transported into some police academy metaverse.

The community engagement simulations though were less convincing, a problem as Axon leans heavily into its pitch that VR can rebuild empathy and potentially reduce police misconduct, which has led public confidence in the police to some of its lowest levels in decades. Axon hopes its narratives can educate police on the complexities of responding to individuals in high-stress environments, but experts worry even the best narratives risk falling victim to biased interpretations.

I spoke with Carl Takei, a Senior Staff Attorney at the ACLU focused on policing, who said the biggest issue he saw with VR training revolves around who is selected to author the training and what assumptions and viewpoints are embedded into that authorship.

“The use of VR and technology can make the training feel more realistic, but it is still going to carry the perspective of the author into the training,” Takei said. “So to change the underlying technology isn’t going to change the nature of the training if it’s still the same people writing it.”

Takei viewed Axon’s decision not to include victims of police brutality in the narrative writing process as a mistake. “If you’re going to accurately describe the experiences of somebody experiencing a police encounter, you should be including people who have been the subjects of police encounters,” he said.

Those concerns certainly rang true in my demo involving the woman struggling with addiction. The entire experience felt like something out of an 80’s era cop movie drama, where a chiselled Clint-Eastwood-inspired hero uses his unflinching moral aptitude to save the day and get the lady “clean.” I remember one particular line my character uttered during that interaction that made me nearly trip my $US1,300 ($1,805) headset off in laughter.

“Somebody once told me there are only three outcomes for people on drugs,” my character growled. “They either end up sober, in prison, or dead. What are you going to pick?”

To get a sense for what cops think of Axon’s product, I spoke with Master Corporal Michel Eckerd, who serves as the Public Information Officer at the New Castle County Division of Police in Delaware, one of several departments testing the company’s community engagement training and VR firing range. Eckerd claims 92% of his agency’s officers have gone through the community engagement training. He said the mobility of the technology was a key selling point for his department.

“The portability of this unit is paramount,” Eckerd said. “At 3:00 in the morning, you can slide back into headquarters or a substation, put on a VR headset, have someone monitor you and get your training out of the way or sharpen your skills,” Eckerd said. “Cops will use that. They will almost abuse it they’ll use it so much.”

Eckert said the Axon VR system currently lives in the department’s headquarters but predicted they’ll soon be assigned to police cars. In theory, one supervisor could potentially provide access to the four or eight cars reporting under them.

Hard data on VR’s effectiveness for policing remains sparse

Even if you find Axon’s argument for VR training convincing, there’s still another pesky problem: it’s almost impossible to currently verify whether any that VR training is actually making a difference. In its advertising and in a presentation shown to Gizmodo, Axon points to a National League of Cities report: 81.4% of participants using Axon’s community engagement VR simulator in the Phoenix Police Department said at least one of the modules prepared them for a real-world call. 59% said at least one of the modules helped them see things from another perspective, a tick in favour of Axon’s claims its VR system can help build empathy. The figures are encouraging but limited. They only take into account qualitative responses from a single police department. The numbers have nothing at all to say about whether or not Axon’s VR tools can actually reduce violent encounters with police. Though the company may have received plenty of feedback from its law enforcement partners, there’s an absence of any rigorous, independent research to bolster those marketing claims. Axon acknowledged that point during our presentation and said it’s currently looking into potential third-party studies of its VR simulator.

There’s also significant disagreement over whether VR actually has any meaningful effect on increasing empathy, a core foundation upon which Axon’s community engagement VR system is built. Studies outside of law enforcement have shown VR simulations can improve training effectiveness and retention. There’s also a growing body of research showing that VR may engender empathy, with Meta’s Oculus crowing that its headset was the “ultimate empathy machine” in an ad in Wired. That same research points to only surface-level engagement from users, however. A 2021 meta-analyses of 43 different high equity studies published in the journal Technology, Mind, and Behaviour, found VR can improve emotional but not cognitive empathy. Basically, viewing experiences in VR can indeed make you immediately feel something, but they fail to get users to actually think deeply about what that means. The study also found VR experiences weren’t any more efficient at arousing empathy than cheaper alternatives like reading fiction or acting.

“Given the cost of VR technology, these results suggest that in some situations, less expensive, non-technological interventions may be just as effective at eliciting empathy as VR,” the researchers write.

In an interview with Gizmodo, Santa Clara University Associate Professor Erick Ramirez, who has previously written critically on the prospect of VR as an “empathy machine,” said he saw some potential for behavioural training in virtual reality but was sceptical that the bite-sized, convenient nature of Axon’s system would actually get the job done.

“It really seems like if you are going to be training law enforcement officers, it can’t be structured this way,” Ramirez said. “It can’t be a five to 15-minute experience that is marketed as a kind of game. That’s just not going to do much of anything.

Ramirez went on to say VR training works best when it gets close to recreating the situations that appear in real life, things like fear and adrenaline. That takes time and deep, serious connections with the content being consumed.

“I have doubts about this kind of simulation’s ability to make you really feel like you are in the real situation,” he added. “This way of approaching training is very unlikely to work.”

Ramirez likewise expressed concerns over the lack of input from victims of police brutality in the VR simulation’s narrative crafting process.

Axon’s mixed record with new technologies

Axon has faced pushback from privacy and civil liberty groups for its body cameras and Tasers long before VR came on the scene. While Tasers offer a meaningful, less-lethal alternative to handguns, they aren’t non-lethal, as Axon has advertised them to be. Tasers have led to the deaths of at least 500 people since 2010, according to reporting by USA Today and research from the site fatalencounrters.org.

Despite Tasers’ intended purpose of reducing police lethality, Takei says the introduction of Tasers has counterintuitively led to an increase in the use of force.

“The broad deployment of Tasers and other less-lethal weapons have actually increased the use of weapons overall, “ Takei said. “There’s a sort of scaling up of harm and force because of the existence of these additional technologies.”

Body cameras intended to reduce violence and expose police misconduct have seen widespread adoption by state and local police departments around the country, though actual research showing they lead to a reduction in use of force remains a mixed bag at best.

The mass deployment of those cameras has vastly increased the amount of public video data generated by police, something privacy advocates and civil liberties groups view with unease.

“Because body cameras can roam through both public and private spaces, they capture enormous amounts of data about people beyond those interacting with the police officer wearing the camera,” ACLU Washington Technology & Liberty Project Manager Jennifer Lee wrote last year.

In the end, critics of Axon’s VR and other glitzy new technologies like Takei of the ACLU worry over-investment in technological solutions risks overshadowing more practical fixes that that strive to limit the amount of interactions between cops and everyday people.

“How much as a society are we gonna just rely on policies and training to try and change police behaviour,” Takei said. “Does it make sense to spend a lot of money on new technologies on police officers to respond to behavioural health crises, or does it make more sense to invest money into building up mobile crisis response teams and clinician-led teams that can respond to behavioural health crises in radically different ways than the police do?”