If you’re one of the cursed few who has not heard of the Locked Tomb series, now is the perfect time to be introduced. Tamsyn Muir’s science-fantasy debut, Gideon the Ninth, rocked the lit-o-sphere, running amok among queer fans, science-fiction nerds, and selling out a dozen times over. The sequel, Harrow the Ninth, continued the gory, bizarro legacy, and the story continues with Nona the Ninth, preparing to crash land onto shelves later this year. Gizmodo is thrilled to share an exclusive excerpt today.

Muir’s prose is weird, shifting, baroque, dense, complicated, and exciting. As quick as perspectives shift, so do the reader’s understandings of the narrator, the magic, and the world. And Nona, which picks up half a year after the end of Harrow the Ninth, looks to deliver much of the same.

Her city is under siege.

The zombies are coming back.

And all Nona wants is a birthday party.

In many ways, Nona is like other people. She lives with her family, has a job at her local school, and loves walks on the beach and meeting new dogs. But Nona’s not like other people. Six months ago she woke up in a stranger’s body, and she’s afraid she might have to give it back.

The whole city is falling to pieces. A monstrous blue sphere hangs on the horizon, ready to tear the planet apart. Blood of Eden forces have surrounded the last Cohort facility and wait for the Emperor Undying to come calling. Their leaders want Nona to be the weapon that will save them from the Nine Houses. Nona would prefer to live an ordinary life with the people she loves, with Pyrrha and Camilla and Palamedes, but she also knows that nothing lasts forever.

And each night, Nona dreams of a woman with a skull-painted face…

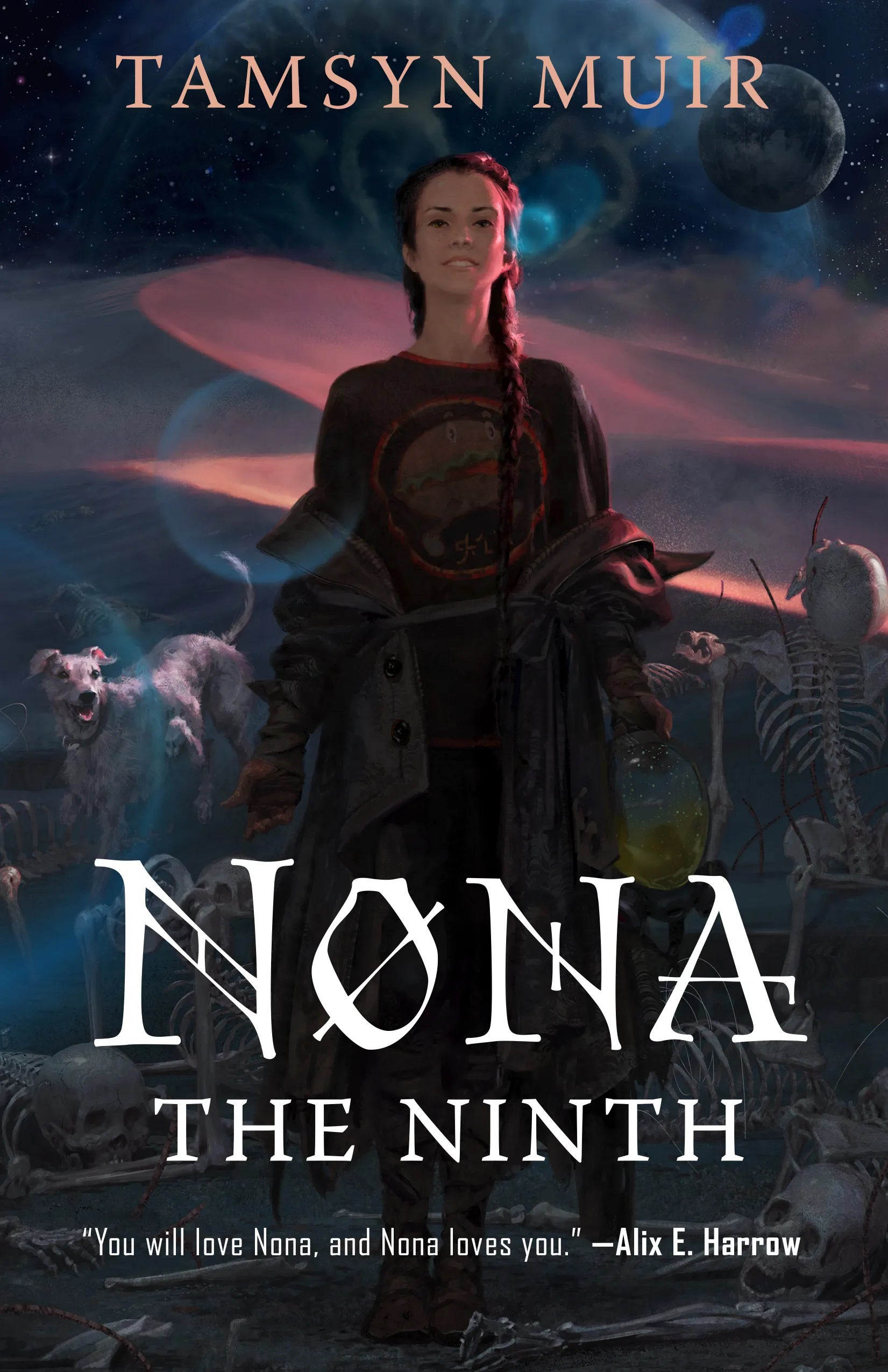

Here’s a look at the full cover, followed by an exclusive excerpt from the book’s second chapter.

What she definitely knew was that her body belonged to one of two people, and she was interested in her body. When she looked in the mirror she had skin the colour of the egg carton, and eyes the colour of the egg mixture, and hair the colour of the burnt-out bottom of the pan. More to the point, Nona thought she was gorgeous. She had a thin, complicated face, and a mouth too easily unhappy and too easily discontented; but she had nice white teeth in a smile that looked sad no matter how happy she was, and arched black brows like she always wanted to ask someone a question. Nona talked to herself in the mirror even now. When she had been earlier born, and less self-conscious, sometimes she would rest her face against the mirror’s face, and try to reach her reflection. Camilla had caught her kissing it once, and had written about six pages of notes on that, which was humiliating. It was hard enough not to be allowed a single solitary secret, without a book being written about whatever you did. If Camilla had six pages of notes on her kissing herself she had about twenty regarding eyes. Nona’s egg-yellow eyes belonged to the other person — the other girl; that was how all of their bodies worked, not only hers. All four pairs of their eyes belonged to other people. Pyrrha’s deep brown eyes really came from her dead best friend, and Camilla’s clear grey eyes should have really been Palamedes’s, and vice-versa with his wintertime irises. Nona’s eyes were a deep, warm gold, the colour of the sky at midday — or at least the colour the sky had used to be at midday.

“You see,” Palamedes had said to her, “the eyes are a dead give- away. When you give yourself to someone else, their soul shows in yours by the eye colour; that’s why you’ll never see me looking out of Camilla’s face with my own eyes again.”

“So someone’s inside me, then? I mean — I’m that somebody?” She always stumbled over this.

“Maybe yes, Nona, maybe no. Eyes can also show that a soul is in someone else’s body temporarily. Your amber eyes could mean that you’re like Camilla and me, or it could mean something else. But you seem to have had . . . a big shock.”

“Maybe I’ve just lost my memory,” said Nona dubiously. “It happens,” agreed Palamedes — not convinced.

She didn’t care whose eyes were whose; but she was a little vain, and cared about being nice-looking. Nona knew early that other people thought she was pretty too. Once a long time ago when she was waiting in line to pick up some detergent and Camilla was getting something else they’d forgotten, the person in the line behind her had said, “Hey, pretty thing, where have you been all my life,” and laughed a lot when Nona said truthfully that she didn’t know. Then they had stood quite close to her and touched her on the hip, where her shirt was tucked in. The shop was very crowded and there were a lot of people waiting to get things, and the aisles were packed high with stuff, and there were people the shop paid to make sure nobody stole things, and they added to the crowd. Nobody was paying them any attention.

When Camilla came back the person was still trying to talk to her, and Nona had to translate what they said to Camilla, and Camilla looked the person deep in their eyes and casually touched the hilt of the knife she kept down the waistband of her trousers, and then the person moved to the back of the queue.

“If someone touches you again, and it’s not me, and it’s not Palamedes, and it’s not Pyrrha,” Camilla had told her later, “move away. Get one of us. You don’t know what they want.”

“They wanted to see me naked,” said Nona. “It was a sex thing.” Camilla had made a sound, and then pretended it was a cough, and drank a whole glass of water. After the glass of water, she said, “How did you know?”

“That’s just the way people look when they want to see you naked and it’s a sex thing,” said Nona. “I don’t really mind.”

After a moment, Camilla had told her it wasn’t a great idea for Nona to let people she didn’t know see her naked, and not to encourage sex things. She said sex things were right out. She said there were enough problems in the world. Camilla said it was bad enough that she had used to help Nona in the bath. Camilla had also written down a lot more notes.

That was after Nona could talk, but before she started making herself a useful member of society. It was difficult living with Pyrrha and Palamedes and Camilla in those early days and feeling as though she couldn’t contribute much. They worked so hard for her. Pyrrha was an excellent planner and good with her hands, and if you gave her five seconds to talk she could make anyone believe anything, so they ate quite a lot off the money she won at cards. She ran them all with what Cam said was military efficiency. Pyrrha was the one who made them learn code words for all clear and danger, which changed every week. Nona got to be the one who picked them on weekends because that helped her to remember. Pyrrha also gave them special emergency code words for “someone following” (red ribbon) and “someone listening” (fritters). They even had a code word for “important resource, come help me get it” (fishhook), but Palamedes said Pyrrha needed to stop treating cigarettes and scotch as import- ant resources, so they hadn’t used that one in ages.

Pyrrha could cook, and she was tough, and if you went up to the roof of the apartment building and put a marble on top of a certain column, she could close her eyes and raise a rifle and shoot the marble from the other side of the rooftop. She wouldn’t do this lately even if Nona asked, because bullets were expensive right now (but a lot cheaper than meat). So Pyrrha could earn money and fight with a gun. She was also very wonderful with a sword, but she never lifted a sword unless all the curtains were drawn and the door was locked. They hid the swords behind a false board in the cupboard.

Camilla could fight with pretty much anything, and especially knives — she wouldn’t do the marble trick with her knife because she would just say, “What did it do to me?” and then smile her tiny beautiful smile. Palamedes said that was typical. It seemed like there was nothing Camilla couldn’t do after a few tries — the laundry, or starting up a truck, or opening a door when she didn’t have the keys, or telling the drunk man at the bottom of their hall that none of them liked it when he hit his partner, in a mystical way that caused the man to move out of the apartment forever.

Palamedes could think. He said it was his party trick.

But Nona couldn’t shoot or fight or think. All she had was a good nature — that wasn’t true all the time, but Nona didn’t want it bruited about that she had a bad temper when she had only ever thrown two tantrums in her life and couldn’t remember either of them. Even if she’d been proud of those, you couldn’t brag about two tantrums. Every day she held a sword until she seriously didn’t care about swords anymore, but she still couldn’t fight with one, no matter how big or thin it was. Camilla had wanted to teach her properly, but Pyrrha said not to, that they wouldn’t be able to tell if anything suddenly came back.

Nona couldn’t do the forbidden bone tricks either, even though Palamedes did nearly the exact same thing with big grey lumps of bone as Camilla did with the sword. She had to hold them, and listen when he told her to do nonsensical things — “Pretend you can stretch it; stretch it now,” or “Pretend you can touch the insides; split it open.” He never made Nona feel bad for not being able to do any of these things, only acted like it was interesting that she couldn’t.

In the beginning she hadn’t been able to do much for herself at all, but over time she had remembered how to button her shirts, and tie up her laces, and soap herself in the bath, and pour water into a glass so that her hand didn’t tremble and the water didn’t slop out. It shamed her, remembering how little she could do at the start. She had been so frustrated, in those slow early days. But now she could do nearly everything. She knew important facts like what was expected and what was unexpected at different parts of the day, and that people’s ears weren’t so interesting that she had to put her fingers inside them. In those early days Palamedes and Camilla and Pyrrha had often looked at her in a sort of stupefied shock; now they were still stupefied but they were not so shocked, and often she made them laugh.

And now they touched her, sometimes not even by explicit re- quest. Pyrrha would roughly hug her in one big suddenness, or sweep Nona up in her hard, wiry arms before setting her down on the sofa; Palamedes would pull the blankets up over her if she was getting ready for bed and tuck them in softly at the corners. If she slipped her hand into Camilla’s, when they were walking down the street, Camilla would hold it. Nona didn’t understand how the others could walk around and go through their lives only touching each other as much as was necessary. When Nona asked, Camilla said that this was because they needed to get the washing-up done.

Nona could do all the basic things now, but there was still distressingly little that she was good at. Nona was good at:

- touching,

- wiping dishes,

- running her hand over the flat cork carpet in a way that got all the hair out of it,

- sleeping in lots of different ways and positions, and

- speaking any language that was spoken to her, in person, so she could see the person’s face and eyes and lips.

It turned out that Palamedes and Camilla could only speak one language, and Pyrrha could speak all of that one and some of another two and a little bit of about five more. The one language all three were fluent in was a kind people used for business transactions, so it wasn’t strange that they used it — but it was falling out of favour, because it was a language used by awful people. Even then, the dialect spoken in the city didn’t always make sense to them, or the pronunciation was strange. Nona understood everybody, and could speak back to them so that they understood her, and nobody ever said she had an accent. This confounded Palamedes. When she first said that she could speak back by watching them talk and making her lips look like theirs, it confounded him so much more that it gave Camilla a headache.

There were lots of different languages and dialects around be- cause of all the refugees from other planets, and because of all the resettlements — Nona knew about resettlements because it was all anyone talked about in a queue — and if you spoke someone else’s language they were nicer to you, and assumed you had come from the same place they had come from and lived through what they’d lived through, which was helpful. Many people were suspicious of other people because they wanted a good resettlement and were afraid that other people would somehow get them a bad resettlement. Many people had lived through at least one bad resettlement already. Everyone was crammed on one of three planets now, and they all agreed that this planet was easily the worst, though this al- ways made Nona feel a little bit offended on the planet’s part.

And so Nona lived with Camilla, Palamedes, and Pyrrha, on the thirtieth floor of a building where nearly everyone was unhappy, in a city where nearly everyone was unhappy, on a world where everyone said that you could outrun the zombies, but not forever.

You were not allowed to say the words zombies, necromancers, or necromancy outside her house, or really inside it either. Nona said they talked about everything else, so why not those words, but Palamedes said superstition for the latter and indignation for the former, which Nona did not understand. This had been the case for Nona’s entire life, which would be six months next week, and Pyrrha had said as a treat she would take everyone for a birthday trip to the beach (if nobody was setting up a mortar on it).

Nona was so grateful to have had a whole six months of this. It was greedy to expect much longer.

Except from Nona the Ninth by Tamsyn Muir reprinted by permission from Tordotcom.

Nona the Ninth by Tamsyn Muir hits shelves September 13. You can preorder the book here.

Editor’s Note: Release dates within this article are based in the U.S., but will be updated with local Australian dates as soon as we know more.