A team of researchers studying satellite images of the Alps made a concerning find: Since 1984, most of the high-elevation parts of European mountain range have seen an increase in vegetation. While that might not sound particularly troublesome, this “greening” is likely due to global warming and may be facilitating a feedback loop that is also reducing snow cover.

“When snow and ice recedes, vegetation develops, and that’s what we call greening,” Antoine Guisan, professor of ecology and evolution at the University of Lausanne, told me by phone. Guisan is co-author of a paper about the research, which is published in the journal Science this week. Sabine Rumpf, assistant professor at the University of Basel, led the study.

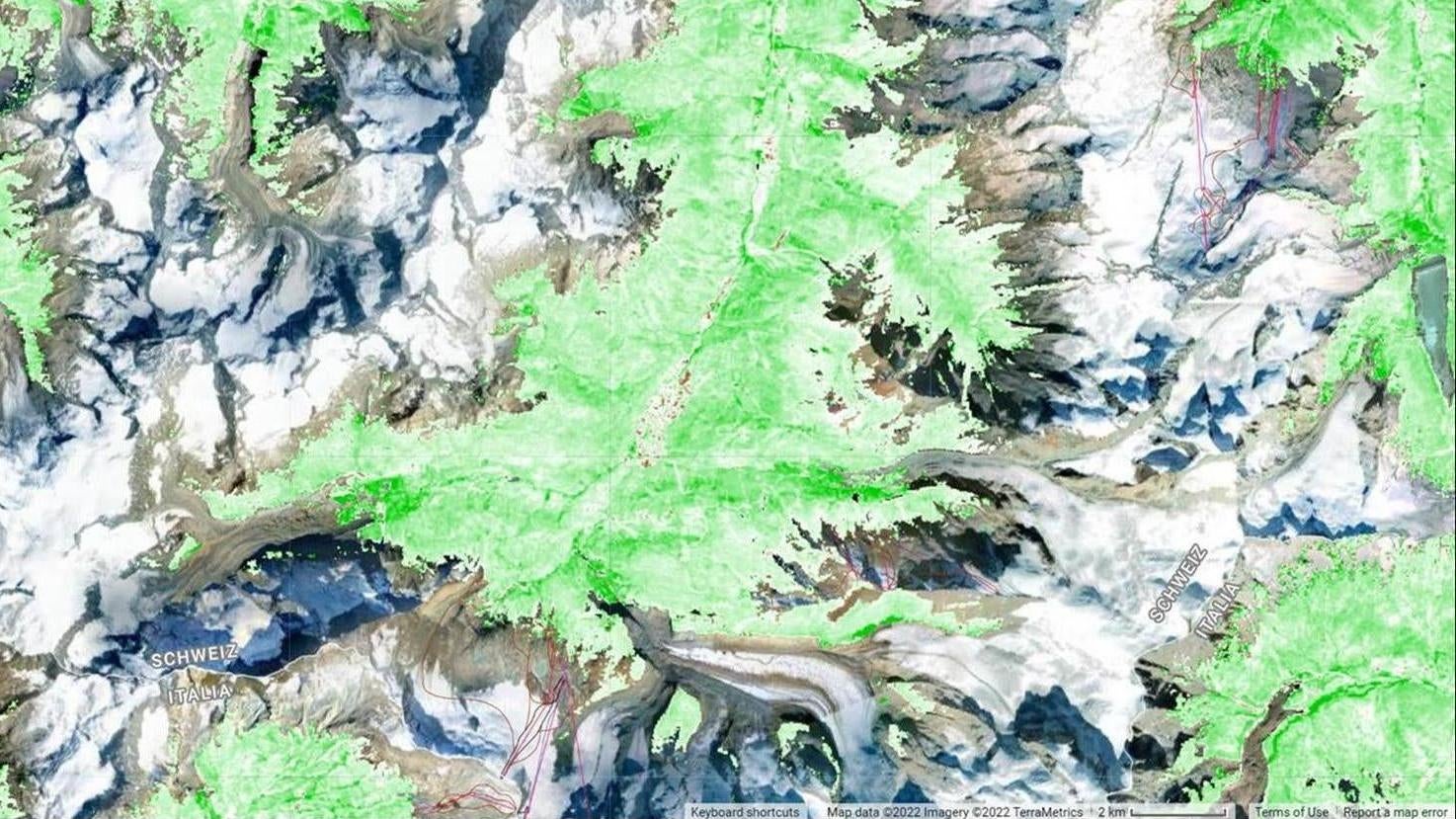

The team collected satellite images taken of the Alps from 1984 to 2021, giving them a comprehensive look at how vegetation and snow cover changed over four decades. They specifically studied elevations above 1,700 metres — this elevation marks the tree line. “Human influence gets increasingly potent below this elevation,” Guisan said, so excluding areas below the tree line helped them zero in on what changes might be due to climate factors.

Rumpf, Guisan, and their colleagues found that significant greening occurred across 77% of the high-elevation Alps. They analysed the satellite images pixel by pixel in order to get an idea of how vegetation and snow cover were changing. Guisan explained: “For the millions of pixels we had for the Alps, we ran an analysis per pixel, and this analysis could show either an increase, no trend, or a decrease.”

Instead of looking at all 12 months of the year, the team pulled data from June through September, since that’s when snow cover is most likely to change. “If you have snow from the beginning of June until the end of September, in one place, it means you have it all year,” Guisan elaborated. Permanent snow cover decreased over 9% of the studied area, they found.

While extra plants don’t sound so bad, the greening of the Alps could have some serious human consequences. Vegetation reflects less light than snow, which means that it absorbs more heat, contributing to additional warming. That could cause a snowpack-loss feedback loop: More greening could lead to more snowpack loss, which could lead to more greening. Annual melting of mountain snowpack is an important source of water for communities around the Alps.

“Typically, the snow is providing water not only for mountain communities but also for lowlands,” Guisan said. A loss of snow cover could also affect ski tourism to the Alps, as well as increase the potential for landslides, he said.

Greening has been documented in other parts of the world, but Guisan said this research aims to address a research gap. “So far, [greening] has been mostly reported in the Arctic, but much less for mountains,” Guisan explained.

While the most dramatic impacts of climate change are currently being seen in the Arctic, studies like this one remind us that the impacts of warming will be felt all over, with domino effects that will be hard to predict.