Hundreds of astronauts have dared to leave the cosy confines of their spaceships and enter into the cold nothingness of space with only their spacesuits to protect them. The spacewalks we present here are among the most memorable to date, though some not necessarily for good reasons.

Only a few things seem more dangerous to me than spacewalks. Now, I would very much like to spend time in space, but you couldn’t pay me enough to venture outside my chosen spacecraft. It takes tremendous courage to perform an extravehicular activity (EVA), and it’s for this reason that I salute the hundreds of astronauts who have done so over the years — these men and women in particular.

The first spacewalk in history

On March 18, 1965, cosmonaut Aleksei Leonov exited his Voskhod 3KD spacecraft, becoming the first human in history to perform a spacewalk. Leonov spent nearly 24 minutes outside of his capsule, of which 12 minutes were spent spacewalking. The historic achievement showed that it was possible for humans to work outside of their spacecraft, but it was not without incident.

Approximately eight minutes in, Leonov’s suit, including his gloves and boots, began to fill with oxygen. Worried that he wouldn’t be able to coil his rope and return through the airlock, the cosmonaut dropped the suit’s pressure down to life-threatening levels, “but I had no choice,” he said many years later, in a decision that likely saved his life.

“I had firm instructions from the research department to report to mission control everything I was doing, even more so my decision to lower pressure inside the spacesuit,” Leonov told the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale during a 2015 interview. “I broke the rules and didn’t report to mission control to avoid spreading panic, and raise a whole host of questions. After all, nobody could have helped me in that situation.”

The first spacewalk in NASA’s history

NASA astronaut Ed White is the first U.S. citizen to perform a spacewalk, which he did on June 3, 1965, only three months after Leonov’s daring jaunt. The EVA, conducted during the Gemini 4 mission, started above the Pacific Ocean near Hawaii and lasted for 23 minutes. White used a hand-held oxygen-jet gun (the image above shows him holding the instrument) to push himself out of the capsule and to move in space.

“Initially, White propelled himself to the end of the 8-metre tether and back to the spacecraft three times using the hand-held gun,” according to NASA. “After the first three minutes the fuel ran out and White manoeuvred by twisting his body and pulling on the tether.”

White pushed his luck with the zip gun, as the astronauts called it, but thankfully not to his detriment. The Gemini 4 spacewalk was not as dramatic as the one performed by Leonov, but it too experienced some issues, including poor communications during the EVA and a stubborn hatch that was difficult to open and close.

“So, when we went to close the hatch, it wouldn’t close. It wouldn’t lock,” James McDivitt, White’s Gemini 4 crew partner, explained during an interview in 1999. “And so, in the dark I was trying to fiddle around over on the side where I couldn’t see anything, trying to get my glove down in this little slot to push the gears together. And finally, we got that done and got it latched.” Had McDivitt failed to close the hatch, both astronauts would’ve assuredly been killed during re-entry.

The problematic Gemini 9A mission

History’s first two spacewalks were cakewalks compared to the third, performed by NASA astronaut Eugene Cernan on June 5, 1966. For this, the Gemini 9A mission, Cernan was to reach the rear of the spacecraft and strap on an Astronaut Manoeuvring Unit (AMU), or “rocket pack,” developed by the Air Force. This objective was not achieved, however, as Cernan experienced multiple issues during the spacewalk.

Cernan could barely move in his pressurised suit (he later described the suit as having “all the flexibility of a rusty suit of armour”) and the task left him physically exhausted and immensely sweaty. He also exhibited a frighteningly elevated heart rate during the spacewalk. The astronaut could barely see out of his fogged-up visor, and upon reaching the AMU he couldn’t strap it on owing to the absence of handholds and footholds. NASA learned many valuable lessons from the Gemini 9A mission, including the need to test spacesuits in pools and to install support structures to assist astronauts during EVAs.

The first spacewalk to conduct space station repairs

When Skylab launched on May 14, 1973, the space station’s micrometeoroid shield fell off and its solar arrays failed to deploy. Later that month, the arriving crew inspected the station, confirming that the shield was missing, along with one of the solar arrays. The remaining solar array hadn’t deployed, as it was pinned down by debris from the torn shield. The mission was off to a rocky start, but these setbacks led to the first repairs of a space station by spacewalkers.

On June 7, 1973, NASA astronauts Charles Conrad and Joseph Kerwin exited Skylab, spending 3 hours and 25 minutes performing the required fixes (it was the longest-ever spacewalk at the time). One particularly scary moment saw the astronauts thrown to space, the result of them freeing a stuck hinge, but tethers prevented them from floating away. As NASA writes, the “success of this repair EVA enabled NASA to plan with confidence the rest of the Skylab program that in terms of the amount and quality of research results obtained far exceeded preflight expectations.”

The first woman spacewalker

Cosmonaut Svetlana Savitskaya is the first woman to perform an EVA, which she did in August 1982 as part of the Soyuz T-12 mission. During her historic 3 hour and 35 minute spacewalk, Savitskaya performed some welding, becoming the first person in history to do so in space. Working alongside cosmonaut Vladimir Dzhanibekov, Savitskaya performed metal spraying and ran tests of a new multipurpose tool.

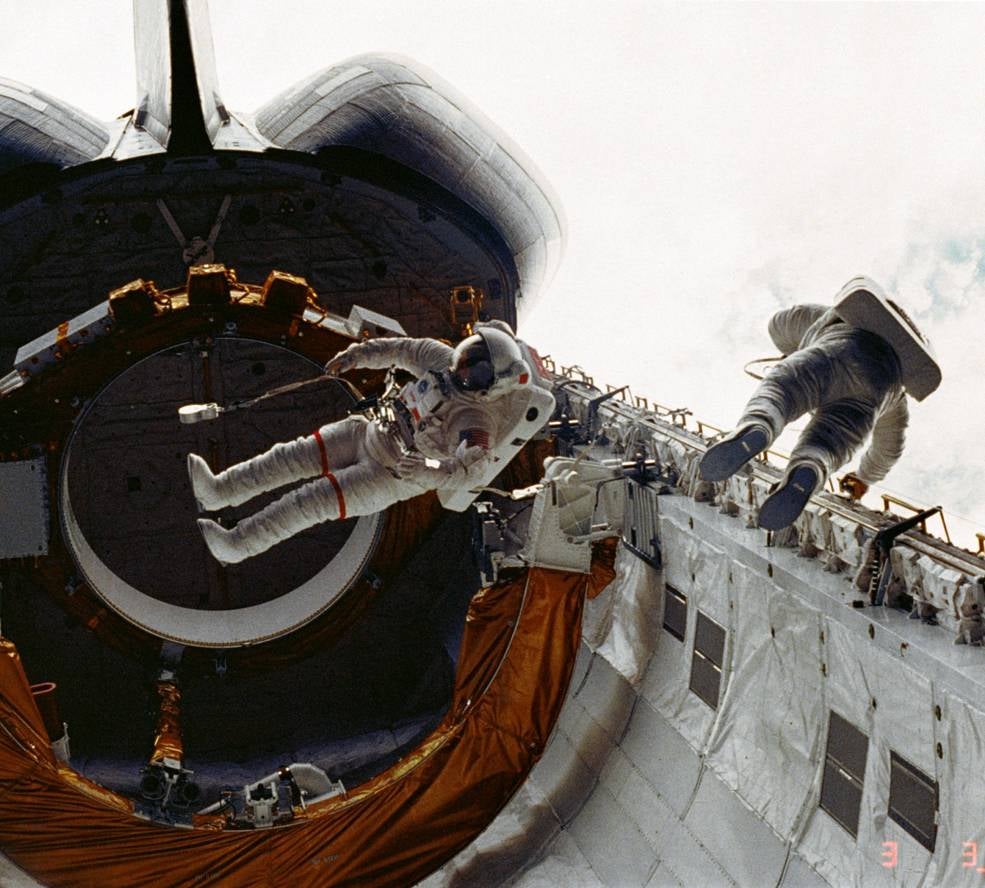

The first Space Shuttle EVA

The first spacewalk to be performed outside the Space Shuttle happened on April 7, 1983. NASA astronauts F. Story Musgrave and Donald Peterson conducted this historic EVA, which occurred during the maiden flight of Challenger.

The first untethered spacewalk

Until 1984, every EVA was performed with a safety tether. That changed during the STS-41-B mission, when NASA astronaut Bruce McCandless achieved an untethered spacewalk while venturing outside the Space Shuttle Challenger. McCandless did so using the Manned Manoeuvring Unit (MMU), which allowed him to drift more than 91 metres from the Shuttle. Two dozen small compressed nitrogen thrusters powered the unit, while a pair of motion-controlled handles on the armrest allowed McCandless to manoeuvre himself through space. This particular spacewalk, I have to say, took a lot of guts.

McCandless, along with crew member Robert Stewart, simply tested the new unit during the STS-41 mission, but it was put to good use during the STS-51-A mission in November 1984, when astronauts used the the propulsion device to capture two communication satellites that failed to reach their proper orbits.

The first EVA outside of the International Space Station

The first spacewalk to be conducted at the fledgling International Space Station happened on December 7, 1988. NASA astronauts Jerry Ross and James Newman worked to connect electrical and data cables between the station’s first two modules, Zarya and Unity.

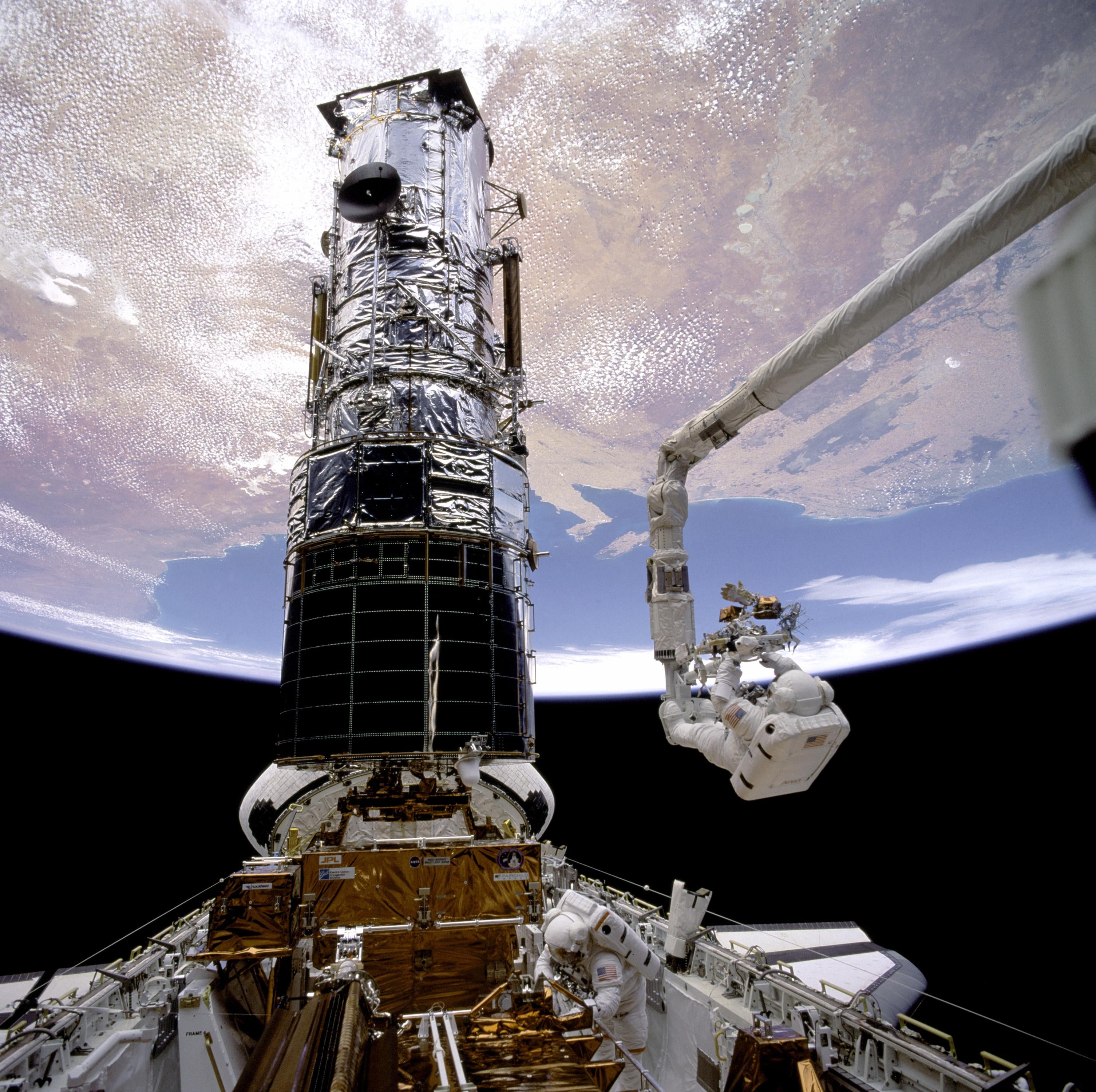

The five Hubble Telescope servicing missions

You wouldn’t know it now, but the Hubble Space Telescope experienced some serious vision problems shortly after its launch in 1990. The problem was deemed fixable, resulting in service missions made possible by the Space Shuttle. These missions were also done to extend the lifespan of the space telescope. Hubble “was the first telescope designed to be visited in space by astronauts to perform repairs, replace parts and update its technology with new instruments,” according to NASA. In total, five service missions took place from 1993 to 2009, requiring astronauts to work outside the Shuttle.

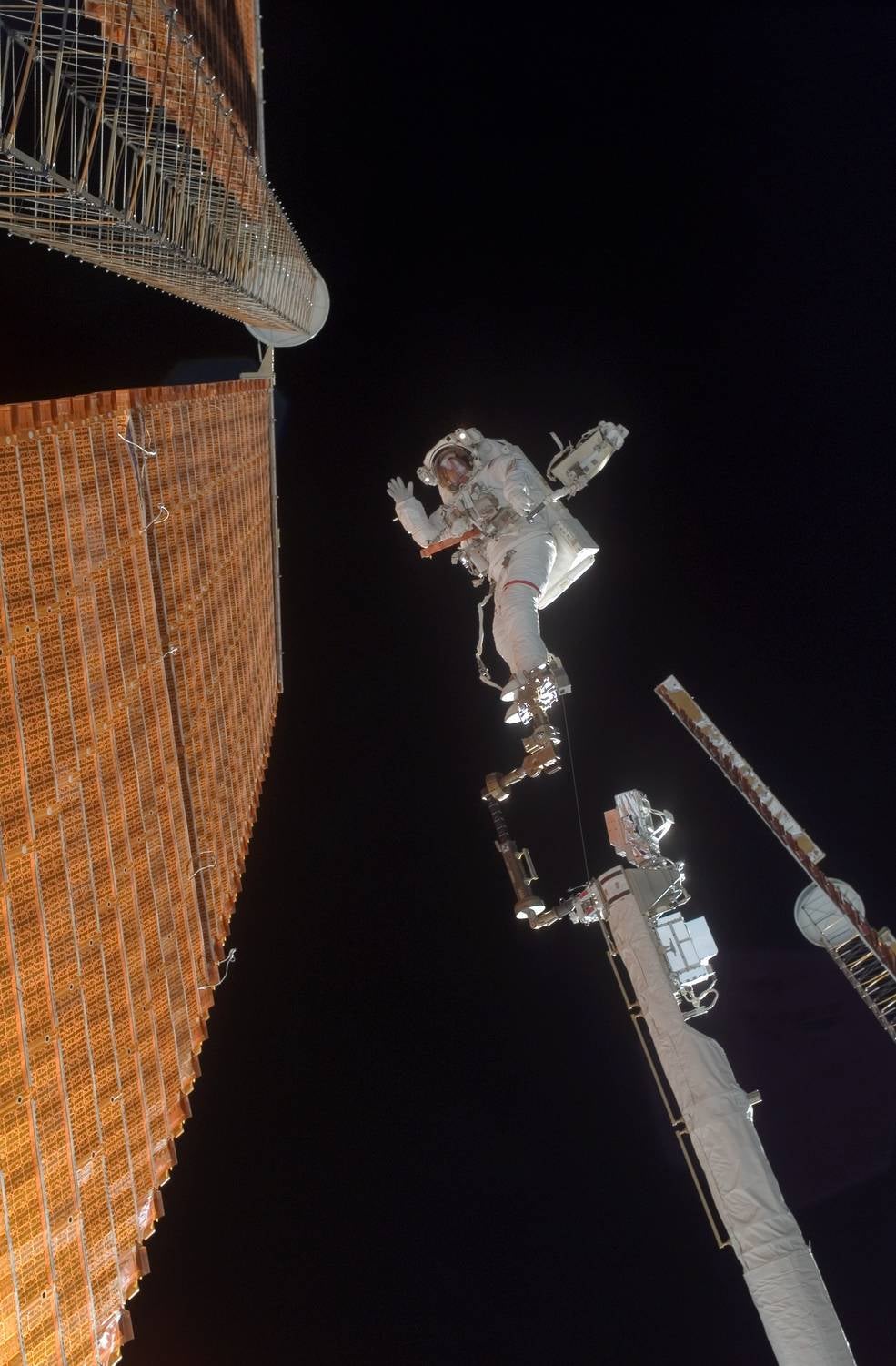

Repairing a torn array

During the STS-120 mission on the ISS, crew members reconfigured the station’s power systems, requiring them to roll up and then unfurl two solar arrays. The first array re-opened without issue, but the second array formed a nasty tear (see image above). NASA explains how the problem was resolved:

Working with the onboard crew, mission managers devised a plan to have one of the astronauts essentially suture the tear in the panel. Appropriately enough, one of the two STS-120 spacewalkers, Scott E. Parazynski, was also a physician and he put his suturing skills to good use. Attached to a portable foot restraint, Parazynski was hoisted atop not only the station’s robotic arm but also the Shuttle’s boom normally used to inspect the Orbiter’s tiles, the impromptu arrangement providing just enough reach for Parazynski to successfully repair the torn array using a newly-designed tool dubbed “cufflinks.” After he secured five cufflinks to the damaged panel, crewmembers inside the station fully extended the array as Parazynski monitored the event.

This was one of the more riskier EVAs, as the image above makes abundantly clear, but the procedure was completed without incident.

The time an astronaut nearly drowned in space

One of the scariest moments in spacewalking history happened on July 16, 2013, when European Space Agency astronaut Luca Parmitano’s helmet filled with water. A blog post written by Parmitano after the incident details his experience in harrowing detail:

The water has also almost completely covered the front of my visor, sticking to it and obscuring my vision. I realise that to get over one of the antennae on my route I will have to move my body into a vertical position, also in order for my safety cable to rewind normally. At that moment, as I turn ‘upside-down’, two things happen: the Sun sets, and my ability to see – already compromised by the water — completely vanishes, making my eyes useless; but worse than that, the water covers my nose — really awful sensation that I make worse by my vain attempts to move the water by shaking my head. By now, the upper part of the helmet is full of water and I can’t even be sure that the next time I breathe I will fill my lungs with air and not liquid. To make matters worse, I realise that I can’t even understand which direction I should head in to get back to the airlock. I can’t see more than a few centimetres in front of me, not even enough to make out the handles we use to move around the Station.

A subsequent test of Parmitano’s suit recreated the issue, showing the frightening build-up of water in the helmet (pictured above). Water continues to be a problem for NASA. This past May, the space agency suspended non-critical ISS spacewalks on account of the issue while an investigation takes place. The issue will likely be remedied with the next generation of spacesuits, but for now these suits, which date back to the Shuttle era, are less than ideal.

The first all-female spacewalk

It took a while to happen, and not without prior controversy, but on October 21, 2019, NASA astronauts Christina Koch and Jessica Meir participated in the first all-female spacewalk. The duo swapped out a faulty battery charger on the ISS’s truss structure.