The typed word dominates our lives today, but it’s still a relatively fresh invention in the timeline of humanity — and despite how drastically printing altered our societies, there’s still a lot we don’t know about its early history. Recently, a team of scientists put some of the earliest known printed documents through a high-powered X-ray examination at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California, to better understand how these texts were produced.

The first printed documents were made in Asia using woodblocks by 600 CE, a process called xylography. Centuries later, Johannes Gutenberg used a retooled wine press and a set of metal pieces to make a couple hundred bibles using movable type, an innovation that drastically sped up the rate at which information could be printed.

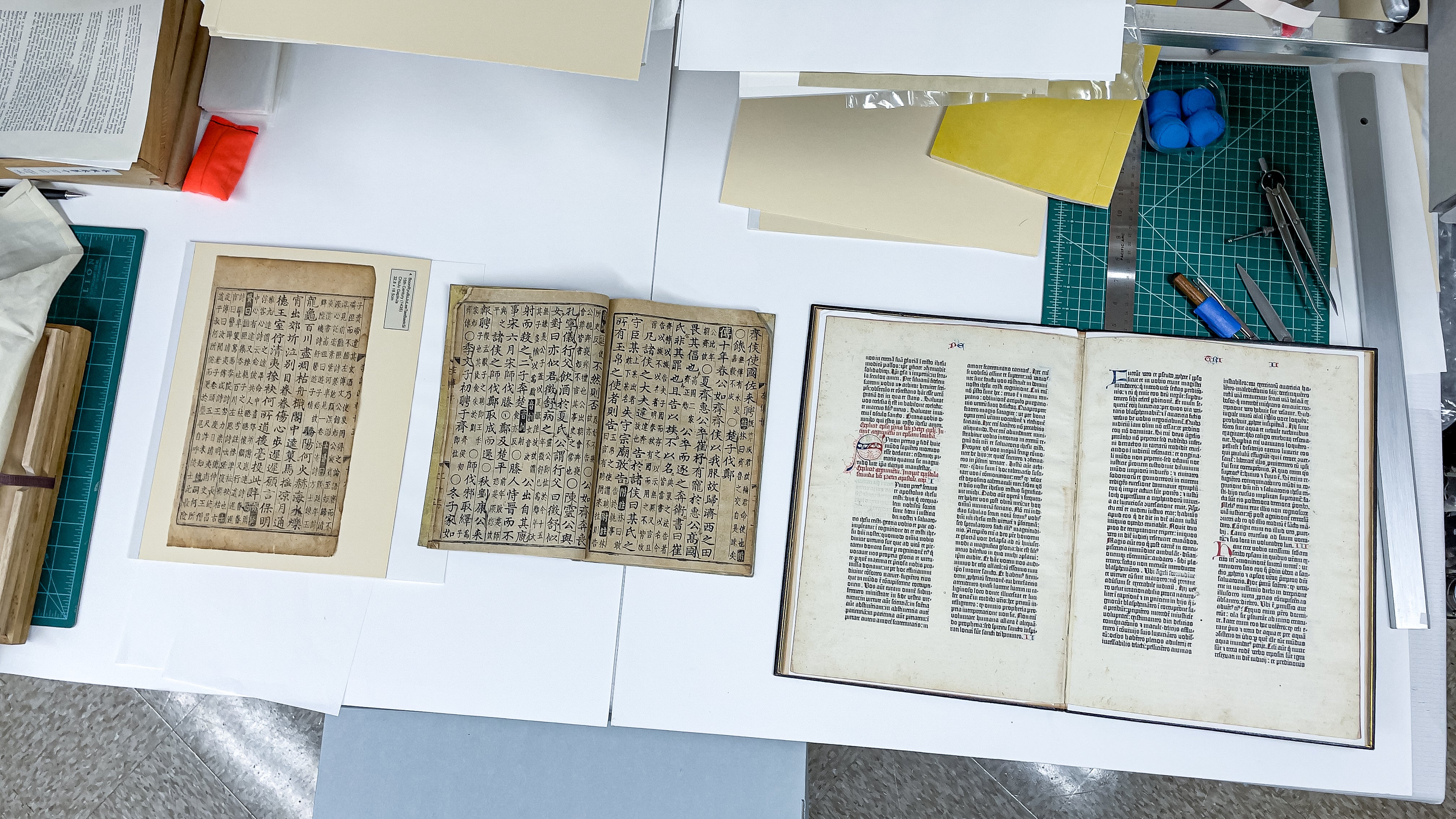

Two documents are of particular interest to the team, which consists of conservators, physicists, archivists, and imaging experts. One is called the “Noble” fragment, two pages of a Gutenberg bible dismembered by a New York antiquarian in the early 1920s, who sold off and donated individual leaves of the book. Only 20 Gutenberg bibles remain fully intact today. The other is a set of pages from the 580-year-old Spring and Autumn Annals, an example of Korean moveable type printing that dates to 1442, preceding Gutenberg’s work by several years. It’s an early printed edition of some writings of Confucius.

“It is undisputed that the Chinese and Koreans had invented a movable type print much earlier than Gutenberg,” said Uwe Bergmann, a physicist at the University of Wisconsin and a member of the team. “What we want to know is, how did it start? And did Gutenberg know? Did he know about the Korean early print or not? Was his invention completely separate, or was it guided or influenced by the other invention?”

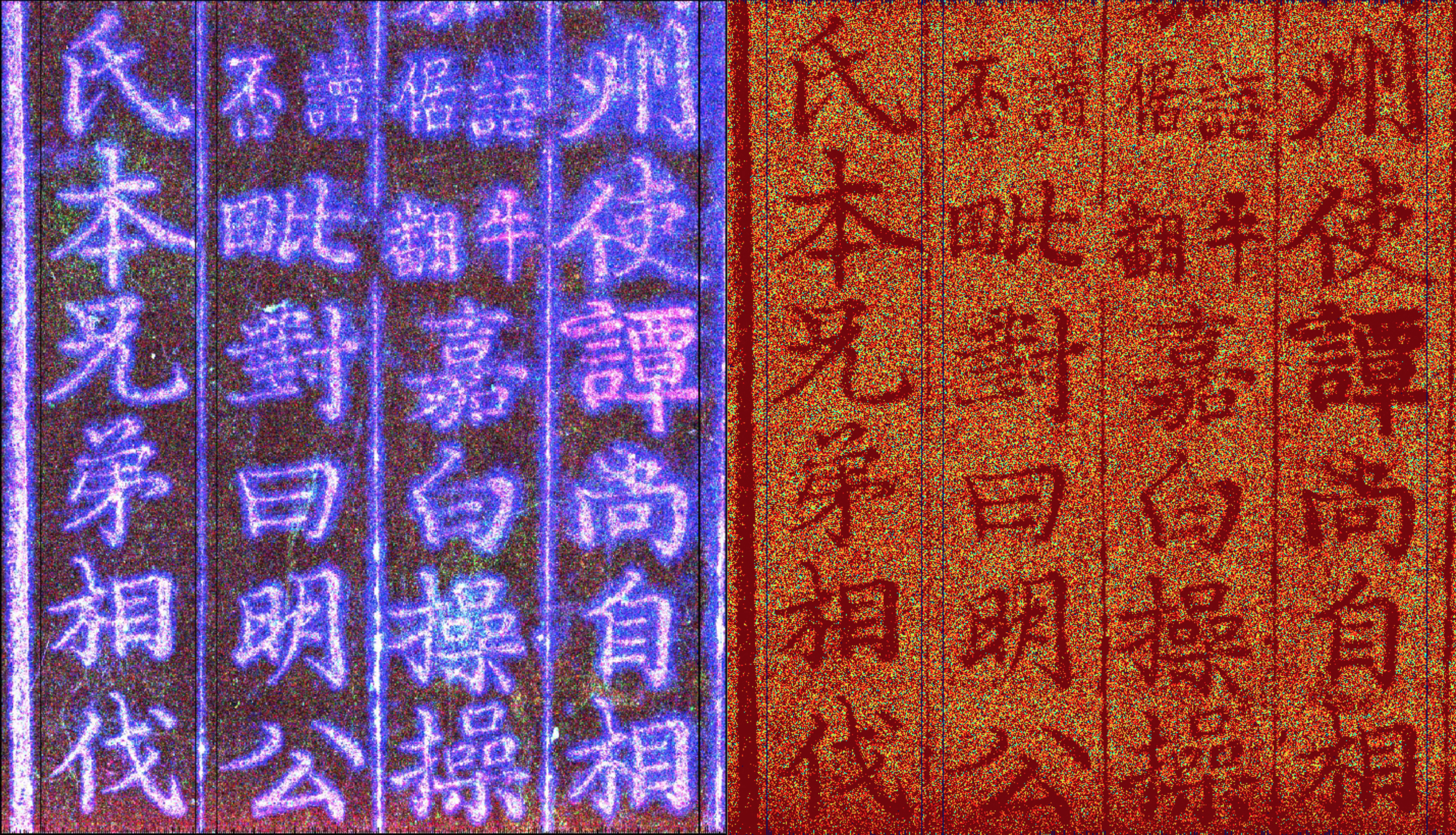

Using SLAC’s synchrotron — a ring-shaped particle accelerator — the team conjured X-rays to peer into the chemical makeup of over 20 Korean printings, the Gutenberg Bible fragments, and other historical documents, including a copy of William Caxton’s “Canterbury Tales.” They aim to interrogate the chemistry of the inks used, as well as what sort of metal types printed the documents.

“We believe that we had an extremely productive first run,” Bergmann said. “We were also happy to observe so much X-ray fluorescence signal of various elements in the inks and paper. Originally, we had not been sure if we would find any substantial signal, but we did.”

Various experimental approaches can illuminate different aspects of historical documents. Raman spectroscopy, for example, can show ink that has long ago faded; researchers recently used it to discover the comments scrawled in the margins of an early version of the King Arthur legend. Multispectral imaging has revealed words Thomas Jefferson decided to leave out of the Declaration of Independence.

The current team is using X-rays because of the way this highly energised light can expose the chemical makeup of their targets. In 2018, researchers at the University of Southern Denmark used X-ray fluorescence to discover that several books in their collection were poisonous, as the green ink in some illustrations was made with arsenic.

“We’ve done what we can with the optical energy levels, and now we’re turning to get more fundamental information with X-rays and X-ray fluorescence,” said Michael Toth, an expert in X-ray imaging systems and a member of the team. “This is to some extent much more difficult, because we’re not looking for hidden text — we’re looking for information we can’t gather from the text itself.”

Back in 2006, members of this research team used X-ray fluorescence to scan the Archimedes palimpsest, a 13th-century prayer book; in 2018 and 2019, they scanned a Syriac translation of Galen of Pergamon’s “On Simple Drugs.” The recent work is the first time in nearly 40 years that X-ray fluorescence has been done on a Gutenberg fragment, according to Toth.

There are some logistical nightmares that come with handling such delicate and important documents. Bergmann said that the Archimedes palimpsest had its own seat in business class when it was flown for the team’s research. And even on the ground, the documents are put into a custom-made sleeve to ensure they’re mounted in front of the synchrotron light source without being damaged.

“As conservators, we’re always trying to understand the material culture we’re tasked with caring for,” said Kristen St. John, a conservator at Stanford University Libraries and part of the team that supervised how the fragile documents would be scanned. “How things are made, the materials used in their creation — all of these things help us to preserve and make accessible these resources that we hold and that are being acquired for our audience of users.”

The project is underwritten by UNESCO, and insights from the scans will be published in the coming months and years. In 2023, the researchers will meet to discuss the findings, and in 2027 they expect to present a larger body of research on the early history of bookbinding and printing.

It may be some time before initial chemical maps of the documents can be analysed and interpreted, but we’ll soon know more about the earliest printing processes than we did before.