An experimental drug for Alzheimer’s disease appears to have shown successful results in a major large-scale clinical trial. The drug’s makers announced Tuesday that their treatment slowed down people’s rate of cognitive decline in a Phase III trial. The findings will likely pave the way for the drug’s approval in the U.S. and elsewhere, but there are still important questions left unanswered about its practical benefits to Alzheimer’s patients.

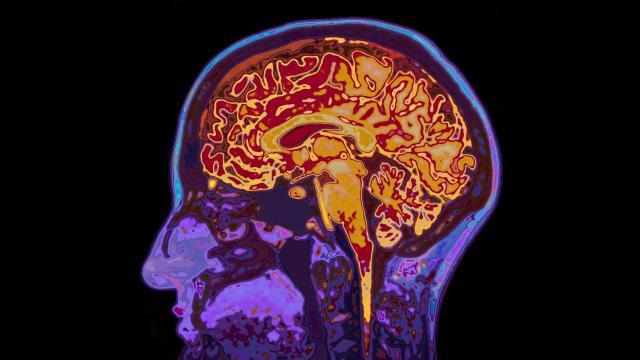

The treatment is known as lecanemab, and it’s being co-developed by the pharmaceutical companies Biogen and Eisai. It’s a lab-made antibody designed to target amyloid beta, a protein naturally found in the brain that’s thought to play a pivotal role in causing Alzheimer’s disease. In those with Alzheimer’s, hardened clumps of amyloid known as plaques build up over time, and these plaques seem to help destroy healthy brain tissue. It’s been theorised that giving lecanemab or similar drugs to patients in the early stages of Alzheimer’s can delay or stop the progression of their condition by reducing the brain’s supply of these amyloid plaques.

The trial involved 1,795 patients diagnosed with early Alzheimer’s or mild cognitive decline that would likely lead to Alzheimer’s. They were randomly assigned to receive either lecanemab or a placebo, then they were monitored for the next 18 months. According to the companies, lecanemab met the primary goal of the study, showing a statistically significant slowing down of further cognitive decline in patients who took the drug. Compared to those on placebo, patients on lecanemab experienced 27% less cognitive decline during the study period. Patients also had lower amyloid levels and appeared to perform better on measures of their daily function.

“Today’s announcement gives patients and their families hope that lecanemab, if approved, can potentially slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease, and provide a clinically meaningful impact on cognition and function,” said Michel Vounatsos, CEO at Biogen, in a statement released late Tuesday night.

The data has yet to be vetted by the larger scientific community, though the companies have pledged to publish the results in a peer-reviewed journal. Assuming they hold up, the findings would certainly be monumental for the field of Alzheimer’s treatment. But there is some important greater context to this research.

This is actually the second anti-amyloid antibody developed by Biogen and Eisai to have shown some measure of success in late-stage human trials. The first treatment was approved by the Food and Drug Administration as the drug Aduhelm in 2021 for Alzheimer’s, but not without major controversy. That’s because Aduhelm’s clinical trial data did not clearly show that it caused a significant reduction in cognitive decline, though it did noticeably reduce amyloid levels in patients.

Against the advice of an outside panel of experts, the FDA chose to approve Aduhelm under a process known as accelerated approval, with the expectation the companies would conduct further studies to confirm its benefits. The decision was widely criticised by outside researchers, with some FDA advisors resigning in protest. And the agency is currently being investigated by government watchdogs over its decision-making process in approving Aduhelm, particularly for the close relationship between some top FDA officials and Biogen during the process. Meanwhile, Medicare eventually took the unusual step of denying blanket coverage of Aduhelm, at least until clear evidence of its effectiveness is collected.

Unlike Aduhelm, lecanemab’s results in this trial appear to be unambiguously positive. That isn’t just good news for Biogen and Eisai but also for supporters of the amyloid hypothesis. For years, every anti-amyloid drug tested in clinical trials has failed to meet its early promise, with Aduhelm either being the only exception or just another example that was wrongfully approved. So if nothing else, it suggests that at least some of these drugs really could help stop or slow down Alzheimer’s, or even that future drugs can improve on this early success.

There is sometimes a crucial distinction between statistically significant and clinically significant results, however. Outside experts have already noted that its effects in slowing cognitive decline are modest and might only represent a few extra months of mental clarity at most. And the drug isn’t risk-free, with patients experiencing a higher risk of brain bleeding in the trial (17% in the lecanemab group vs 8.7% of placebo). That extra time may be worth the health risks for patients and their families to take on. But Aduhelm wasn’t just criticised for its shaky evidence base but for its initially exorbitant sticker price of $US56,000 ($77,739) a year. Biogen has not said how much it expects to sell lecanemab at if it’s approved, but it did eventually halve the overall cost of Aduhelm.

Speaking of FDA approval, the companies say that they plan to file for it by no later than March 2023. It’s almost certain that lecanemab will have an easier time getting approved than Aduhelm did, but many of the thorny questions surrounding the value of these anti-amyloid drugs are likely to linger, even if it is released to the public.

Editor’s Note: Release dates within this article are based in the U.S., but will be updated with local Australian dates as soon as we know more.