NASA’s DART spacecraft was 6.8 million miles from Earth when it slammed into a football stadium-sized asteroid on Monday. Despite this immense distance, images from the impact and its aftermath are coming in, and they’re proving to be better — and far more bizarre — than we expected.

Going into Monday’s test, it wasn’t clear how much of the Double Asteroid Redirection Test we’d get to see. At the very least, we were hoping to get the POV experience from DART’s onboard camera, called DRACO, and views from the shoebox-sized LICIACube, which trailed closely behind NASA’s doomed spacecraft. They didn’t disappoint.

We also knew that telescopic eyes would be watching from a distance, including ground-based observatories and two fairly famous space-based telescopes, Hubble and Webb. Again, they didn’t disappoint.

It’s still early in terms of the data gathering, but the combined result is that we’re getting a reasonably clear picture of what happened when DART slammed into Dimorphos. This is fantastic in terms of engaging the public in what is a very important mission to deflect an asteroid, but also in terms of the science needed to figure out if it actually worked.

Didymos and Dimorphos

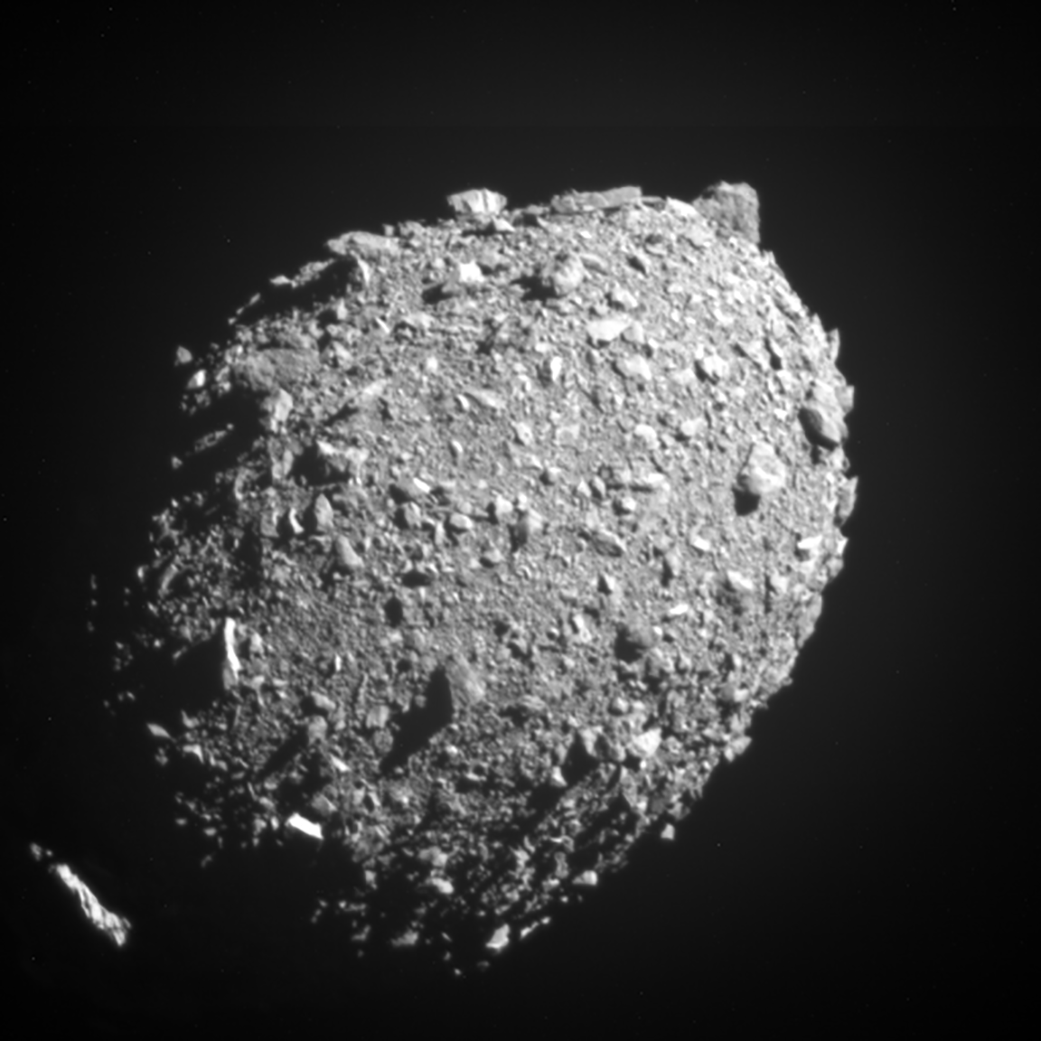

The gravitationally bonded pair are separated by just 3,960 feet (1,200 meters). Didymos, measuring 807.72 m wide (780 meters), was discovered in 1996 and its moonlet Dimorphos, measuring 158.50 m wide (160 meters), was spotted seven years later. We really had no clue what these tiny objects looked like given the vast distances involved, but DART’s high-res DRACO instrument revealed the pair in exquisite detail.

The image above was taken 2.5 minutes prior to impact and at a distance of 570 miles (920 kilometers) to the target asteroid. With DRACO capturing one image per second, and with DART moving at 22,531 km per hour (22,500 km/hr), this is the last image showing the two objects in a single frame.

A jumble of rocks

This, the last complete image of Dimorphos, was taken when DART was 7 miles (12 km) away and 2 seconds before impact. The image revealed Dimorphos to be an egg-shaped “rubble pile,” an asteroid weakly held together by loose conglomerations of debris, including bits of broken-up asteroids and moons.

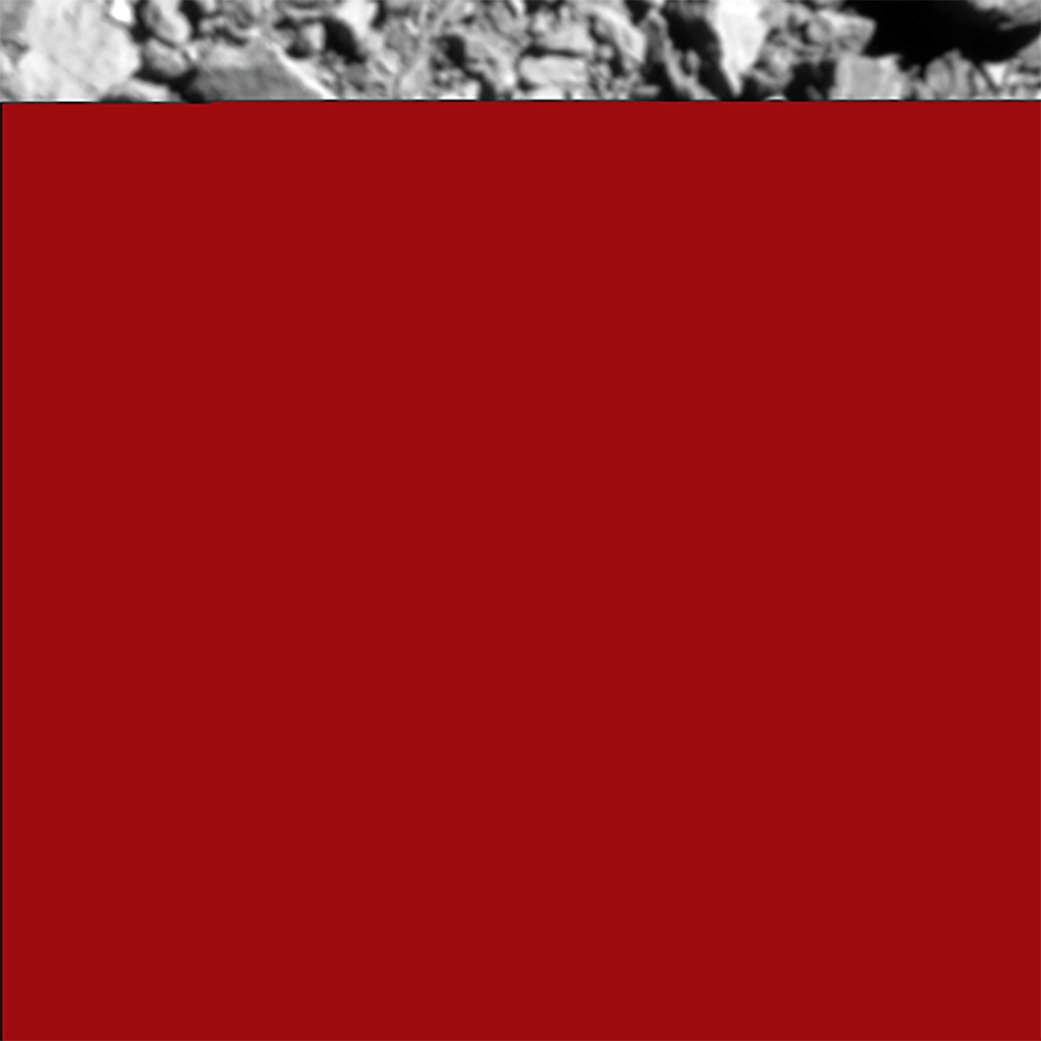

Brace for impact

This tiny patch of Dimorphos is where DART finally met its fate, and it’s the last complete frame produced by the probe. Fair to say, this patch don’t look like that no more, with the 624 kg probe ploughing directly into its target. The resulting kinetic impact, it is hoped, altered the asteroid’s speed and orbital trajectory around Didymos. Ultimately, the experiment could yield an effective planetary defence strategy against hazardous near-Earth objects.

A key goal of the LICIACube mission was to snap post-impact images of Dimorphos. The European Space Agency’s upcoming HERA mission will likewise attempt to gather images of the impact’s effect on the asteroid.

When the loss of signal is a good thing

DART was in the process of transmitting its next DRACO frame when it finally crashed onto the surface. This final image provided our first visual confirmation that the spacecraft was no longer among the living and that DART, with pinpoint accuracy, reached its target following a 10-month journey.

The final five minutes

This stabilised timelapse of the DART experiment shows the final five-and-a-half minutes of the test in just 30 seconds. The video was put together by YouTube channel Spei’s Space News from Germany.

From a safe distance

This stunning view of the impact was captured by LICIACube, which was less than 55 km (55 km) from Dimorphos at the time. DART dispatched the Italian-built probe around two weeks ago and it used its two onboard cameras, LUKE and LEIA, to capture images of the impact and the effect it had on the asteroid. The bright object in the foreground is Didymos.

My, what large streamers you have

An unusually large and complex plume sprouted out from the asteroid as a result of the collision. “I’m shocked by the streamers in the ejecta [the material tossed up by the impact],” tweeted University of Central Florida Planetary Scientist Phil Metzger. In ordinary laboratory impact splash experiments to simulate asteroid impacts “we see nothing like this,” he added.

Big badda boom

Another view of the impact, as imaged by LICIACube, short for the Light Italian Cubesat for Imaging Asteroids. The 31-pound (14-kilogram) probe, Italy’s first deep-space spacecraft, used an autonomous tracker to keep its two cameras locked onto the target asteroid.

Lots to learn

The strangeness of the impact plume will be of great interest to scientists, who will undoubtedly study it in great detail. The resulting insights will shed important new light on the asteroid, such as its composition and volume. LICIACube took some 600 images during the encounter, which it’s currently in the process of uplinking to Earth. Indeed, these four images are only the beginning, as the probe performed a close fly-by of Dimorphos to investigate a possible impact crater and capture images of its opposite side.

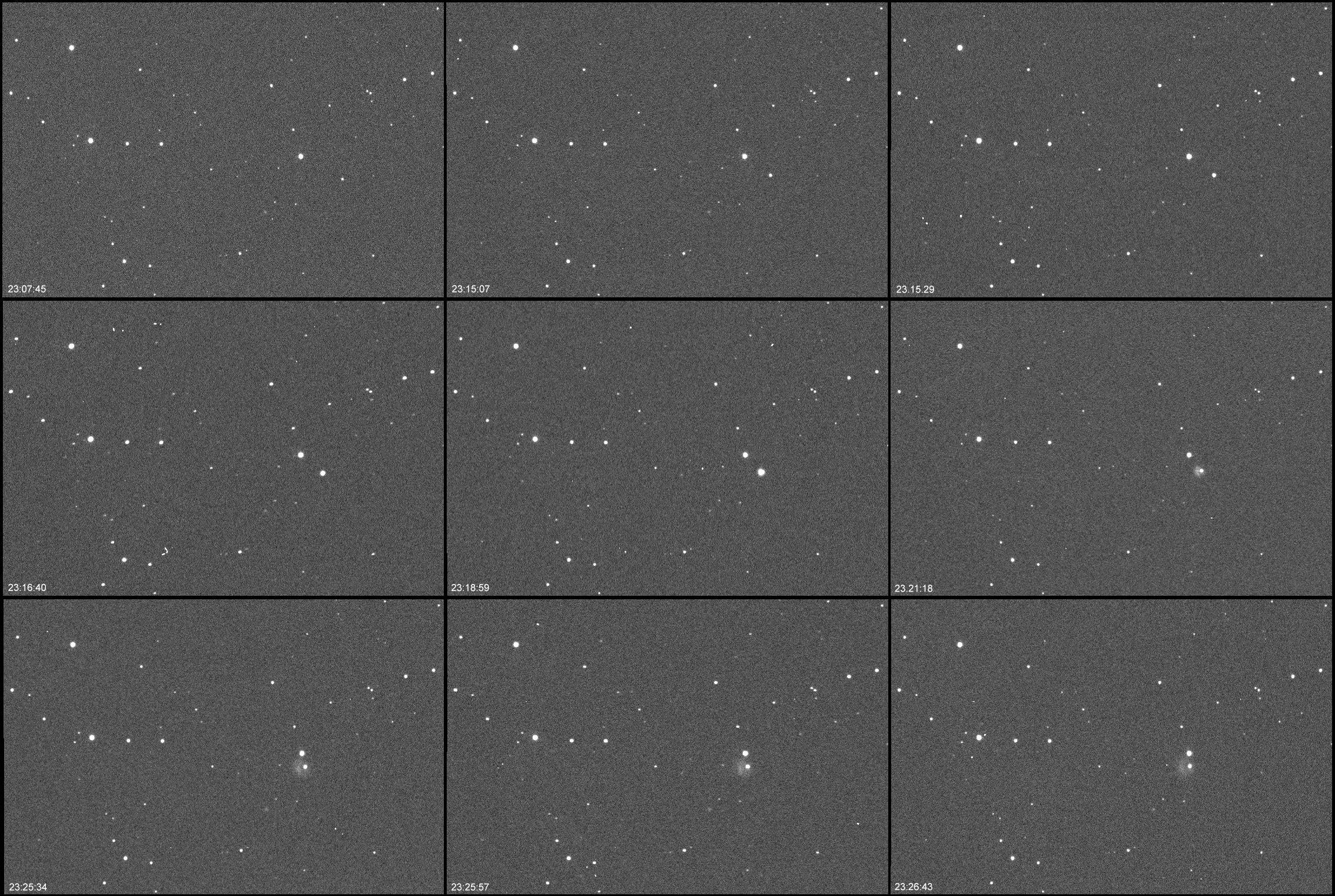

The view from Earth

This series of images shows the progression of the impact plume in the 20 minutes following the impact. It was taken from the Klein Karoo Observatory in South Africa, in collaboration with Italy’s Virtual Telescope Project. From this distance, the binary asteroid system appears as a single dot in telescopic images.

A clearly discernible impact plume

This video of the plume was captured by astronomers at the Les Makes Observatory in Le Reunion, a French island in the Indian Ocean. “Something like this has never been done before, and we weren’t entirely sure what to expect,” Marco Micheli, an astronomer at ESA’s Near-Earth Objects Coordination Centre, said in a press release. “It was an emotional moment for us as the footage came in.” At the time of the impact, Didymos was only visible to observatories in the Southern Hemisphere.

The ATLAS view

The animation above was stitched together by astronomers with the ATLAS project in Hawaii. Ground-based images consistently showed a growing plume moving in the direction of the asteroid. The binary star system is so far that it takes 38 seconds for its light to reach Earth.

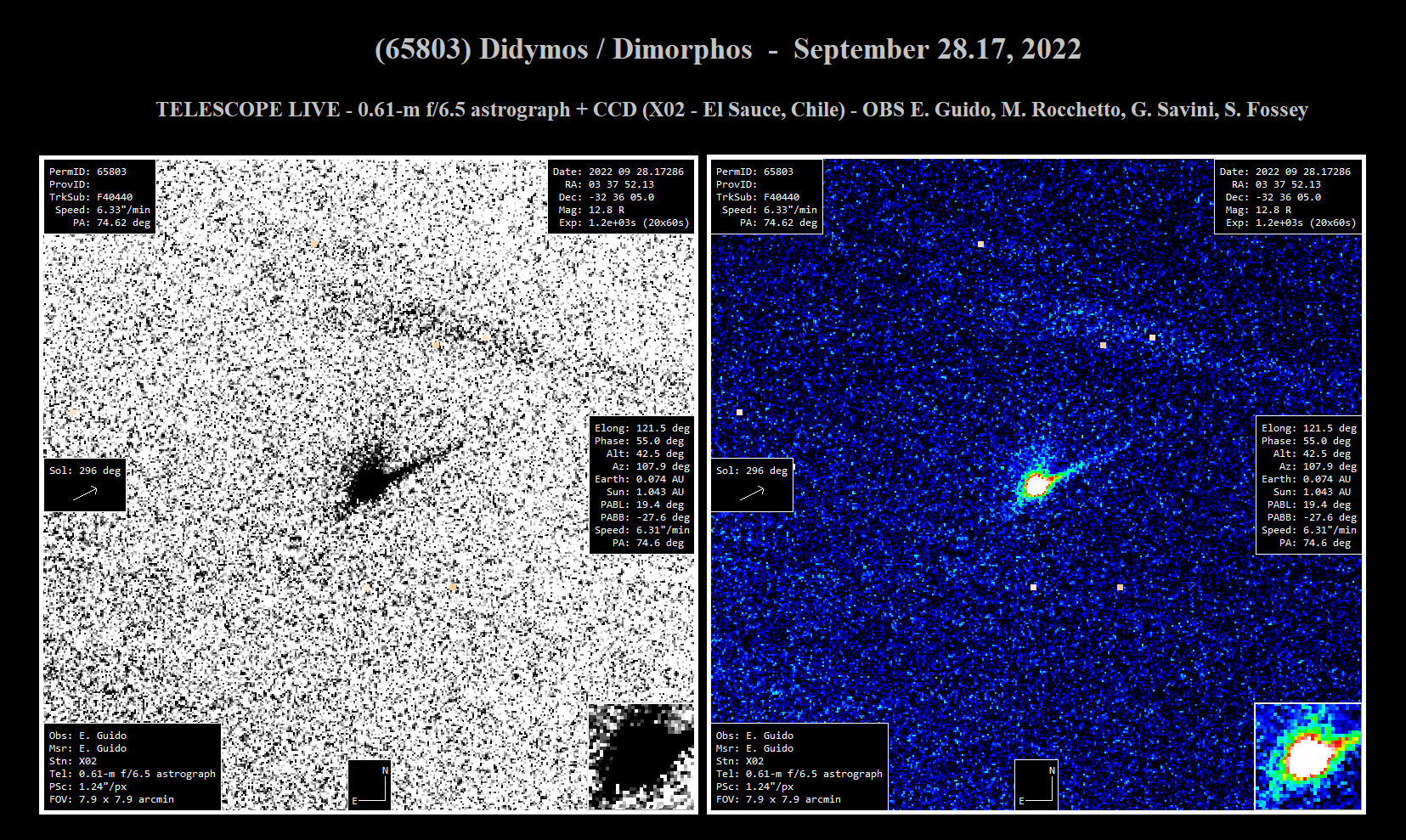

An emerging tail

Italian amateur astronomer Ernesto Guido and colleagues used a 0.6-metre telescope operated by Telescope Live Observatory in Chile to capture this light curve image (showing the light intensity of an object) some 29 hours after the impact. A tail or plume is now visible in the Didymos-Dimorphos system, which may eventually wrap around to form a ring.

The view from space…at a distance

Several space-based telescopes were tuned into the encounter, namely Hubble, Webb, and a camera mounted to NASA’s Lucy probe currently en route to Jupiter’s Trojan asteroids. We’re still waiting for those images to become available, but a preliminary image from Webb (above) is likely the first of many to come. The Webb telescope, which operates from the second Sun-Earth Lagrange point, was approximately 6 million miles (9.7 million km) from Didymos at the time.