Researchers used data from the Dark Energy Survey and the South Pole Telescope to re-calculate the total amount and distribution of matter in the universe. They found that there’s about six times as much dark matter in the universe as there is regular matter, a finding consistent with previous measurements.

But the team also found that the matter was less clumped together than previously thought, a finding detailed in a set of three papers, all published this week in Physical Review D.

The Dark Energy Survey observes photons of light at visible wavelengths; the South Pole Telescope looks at light at microwave wavelengths. That means the South Pole Telescope observes the cosmic microwave background — the oldest radiation we can see, which dates back to about 300,000 years after the Big Bang.

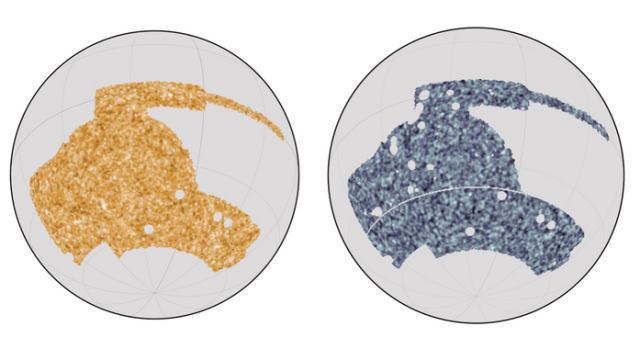

The team presented the datasets from the respective surveys in two maps of the sky; they then overlaid the two maps to understand the full picture of how matter is distributed in the universe.

“It seems like there are slightly less fluctuations in the current universe than we would predict, assuming our standard cosmological model anchored to the early universe,” said Eric Baxter, an astronomer at the University of Hawai’i and a co-author of the research, in a university release. “The high precision and robustness to sources of bias of the new results present a particularly compelling case that we may be starting to uncover holes in our standard cosmological model.”

Dark matter is something in the universe that we cannot observe directly. We know it’s there because of its gravitational effects, but otherwise we can’t see it. Dark matter makes up about 27% of the universe, according to CERN. (Ordinary matter is about 5% of the universe’s total content.) The remaining 68% is made up of dark energy, a hitherto uncertain category that is evenly distributed throughout the universe and responsible for the universe’s accelerating expansion.

The Dark Energy Survey still has three years of data to be analysed, and a new look at the cosmic microwave background is currently being undertaken by the South Pole Telescope. Meanwhile, the Atacama Cosmology Telescope (high in the Chilean desert of the same name) is currently taking a high-sensitivity survey of the background. With newly precise data to probe, researchers may be able to put the standard cosmological model to a difficult test.

In 2021, the Atacama telescope helped scientists come up with a newly precise measurement for the age of the universe: 13.77 billion years. More querying of the cosmic microwave background could also help researchers deal with the Hubble tension, a disagreement between two of the best ways for measuring the expansion of the universe. (Depending on how it’s measured, researchers land on two different figures for the rate of that expansion.)

As means of observation get more precise, and more data is collected and analysed, that information can be fed back into grand cosmological models to determine where we’ve been wrong in the past and lead us to new lines of investigation.

More: Antimatter Could Travel Through Our Galaxy With Ease, Physicists Say