Australia’s coastal cities and surrounding hinterlands have long been popular with tourists, sea-changers and retirees. But they have a darker side. In the early morning you will often find car parks crowded with cars, vans, caravans and even tents, where refugees from the housing crisis have spent the night.

People of all ages, including families with children, are cooking breakfast, using the cold-water showers and packing up for another day, always trying to keep one step ahead of council officers or police. These unhoused people don’t conform to homeless stereotypes. Many have jobs and children in school and no serious mental or physical health problems. They simply cannot find an affordable home to rent, or have lost or are unable to buy a home of their own.

Soaring rates of housing stress are forcing Australians to explore new options, including living smaller and in tiny houses. At Griffith University’s Cities Research Institute, we are surveying local government planners on whether they allow, encourage or limit tiny, temporary or alternative houses in their area.

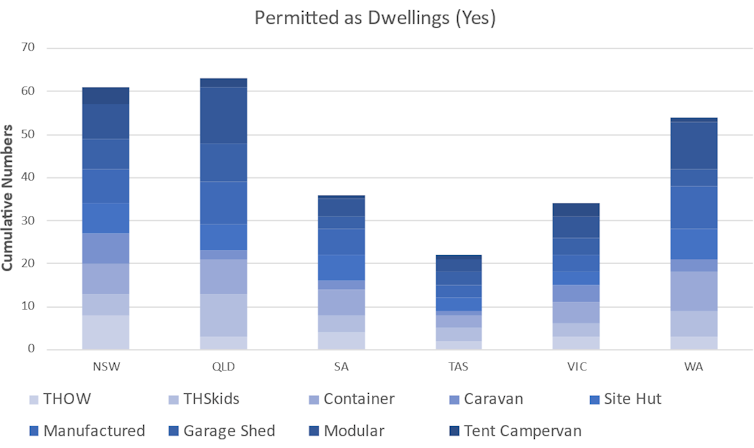

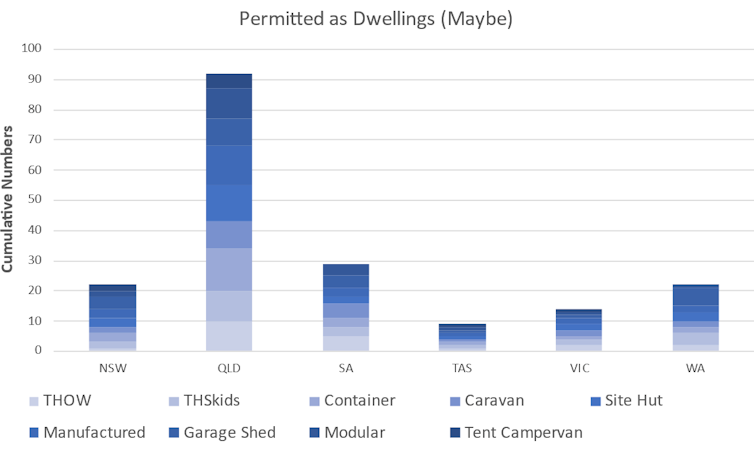

In early findings (from a response rate of over 50% to date), nearly all respondents agree affordability is a problem for both home buyers and renters. While not representing formal council views, their responses indicate most councils now approve modular, manufactured and shipping container houses, despite a public perception they oppose such dwellings. Some have codes specifically for tiny houses on wheels.

As one planner explained:

We will have to think differently about how we live, given housing affordability, inflation, susceptibility to emergency events and the like, and perhaps be more lenient on allowing these types of dwellings – whether on a permanent or temporary basis.

All housing must comply with the law

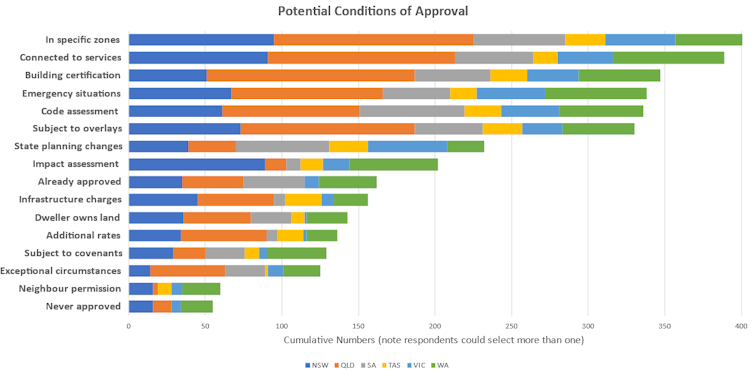

Local governments in New South Wales and Queensland were the most progressive. Many councils (41%) already approve alternative housing types for permanent dwelling. But they must comply with local laws, be in an appropriate residential zone and approved as a residential dwelling, connected to services and protect local amenity.

Data: Cities Research Institute survey/Griffith University, Author provided

Data: Cities Research Institute survey/Griffith University, Author provided

Data: Cities Research Institute survey/Griffith University, Author provided

For example, a planner from a large regional city in NSW said options like tiny houses were possible, “subject to approval and compliance with Planning and Environment Act and Building Act requirements. All need to be approved for permanent use and hence comply with requirements for all dwellings.”

Another NSW planner said:

There are some temporary exemptions in the legislation for disaster event accommodation for up to two years, and [it] had to comply with planning and building act requirements. Local laws become involved if these structures are parked on council land e.g. on the side of the road or on public land. And environmental health issues arise when there is no waste management measure in place.

The Fraser Coast Council in Queensland recently allowed property owners “to accommodate family or friends in a caravan on the dwelling allotment for up to six months in a 12-month period”.

What are the concerns about tiny houses?

Many respondents did voice concern about false advertising by the tiny house industry. As one said:

Tiny houses are the Uber and Airbnb of the housing industry. The idea that such structures can be temporary is in many cases fanciful.

Some manufacturers market their tiny houses as not needing council approval. They fail to mention the requirements that apply to water supply, waste disposal, bushfire and flood risk, and avoiding conflict with agriculture.

[Alternative housing] should be regulated to some extent to ensure that occupants and adjoining neighbourhoods experience a reasonable level of amenity (i.e. not unreasonably put a strain on existing infrastructure, not detract from local character (if prevailing), not cause overshadowing to adjoining neighbours, be fit for purpose etc).

Another concern is tiny houses that don’t comply with building regulations.

Most of these buildings do not comply with the minimum 2.4m ceiling height of the National Construction Code/Building Code of Australia. Even if they do comply […] unless a compliancy certificate has been issued by the manufacturer, there is practically no way of approving them as a certifier has no access to the specifications, can’t visually inspect the frame prior to cladding etc.

Data: Cities Research Institute survey/Griffith University, Author provided

A quest for creative solutions

The tiny house movement, despite its limitations, could help deliver some of the creative solutions the housing crisis demands. It has sparked an important conversation about alternative housing solutions, with broader implications for housing design, construction, regulation, finance and insurance.

I personally would like to see more flexibility in allowing diverse house types (including temporary dwellings) to put less financial strain on people (put people into homes/home ownership who can’t afford traditional houses or can’t find a rental) and create opportunities for alternative lifestyles (i.e. more nomadic, work less, co-op). Keeping in mind there should be measures to preserve amenity.

A focus on good design, adaptability and affordability can make smaller dwellings more attractive to more people. Assembling prefabricated components on site can cut costs.

Tiny homes can be deployed and redeployed quickly if necessary. This is important for areas hit by disasters.

Their small scale offers a way of increasing density sensitively in built-up areas. They can also be clustered together to create new communities.

Conventional strategies such as more greenfield land releases, relaxed planning controls and subsidies for first-home buyers have failed to solve the complex challenges of a seriously dysfunctional housing market. We need to experiment with new approaches to housing, and learn as we go.

Unconventional dwellings like tiny homes can make an important contribution. Our survey suggests planners around the country are willing to join in the process of developing and regulating these news ways of living.

If you work for a local council and would like to participate in our survey, you can find it here.![]()

Heather Shearer, Research Fellow, Cities Research Institute, Griffith University and Paul Burton, Professor of Urban Management & Planning and Director, Cities Research Institute, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.