December and January represent breeding season for seabirds in Antarctica, a time when there should be thousands of active nests. But strong snowstorms during the 2021-2022 season made it difficult for birds to access their usual grounds and resulted in a total failure to reproduce for multiple species.

A recent study published in the journal Current Biology found that, from December 2021 to January 2022, almost no birds nested and laid eggs. Breeding failures have happened in the past, but an almost complete failure to breed is rare and concerning, the scientists wrote in the study.

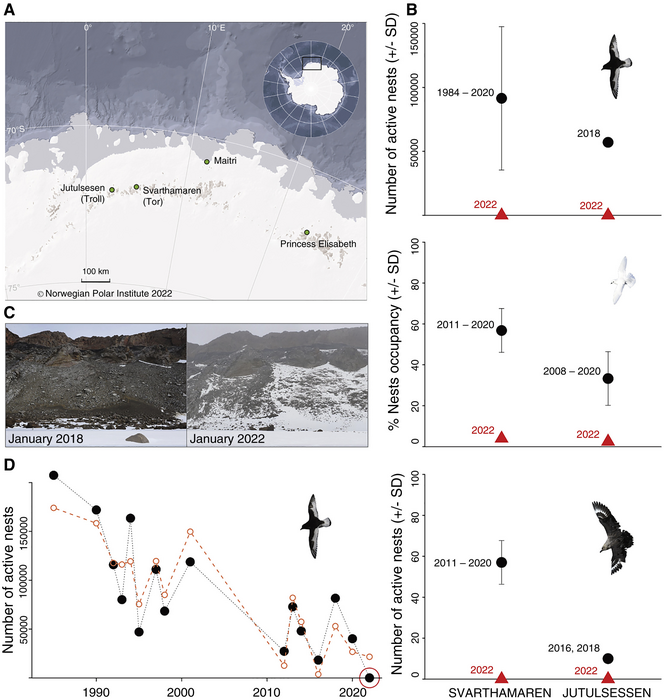

The team looked at breeding in colonies of Antarctic petrels, snow petrels, and skua birds in Droning Maud Land. It’s a region that’s about a sixth of Antartica and is claimed by Norway. It’s home to two of the largest colonies of Antarctic petrel colonies, as well as nesting grounds for snow petrels and south polar skua. The Antarctic petrels lay their eggs on the ground, and snow petrels breed in crevices and cavities, but higher than average snow accumulation made it hard to access those areas. Researchers found that, in January 2022, more than 50% of Antarctic petrel breeding area around the Svarthamaren mountain in Droning Maud Land was covered by snow.

The problem isn’t just affecting some of the birds. Observations from 1985 to 2020 found that there were anywhere from 20,000 to 200,000 petrel nests around Svarthamaren. There were also 2,000 snow petrel nests and about 100 skua nests in a given year. But during the 2021 to early 2022 season, there were only three breeding Antarctic petrels, a “handful” snow petrel nests, and no skua nests. Researchers also noticed that breeding season had poorer feeding conditions. Skuas feed on Antarctic petrel eggs and chicks, and since those birds did not breed successfully in the 2021-2022 season, skua colonies had fewer food options.

“We know that in a seabird colony, when there’s a storm, you will lose some chicks and eggs, and breeding success will be lower,” Sebastien Descamps, the first author of the study and researcher at the Norwegian Polar Institute, said in a press release. “But here we’re talking about tens if not hundreds of thousands of birds, and none of them reproduced throughout these storms. Having zero breeding success is really unexpected.”

Past research has found that snowstorms have been intensified by climate change. Rising emissions mean a warming planet, and climate change is often associated with deadly heat waves and less snow. But it also changes weather patterns by taking what is normal and making it more intense — like stronger snowstorms at the South Pole. So much so that even animals that are supposed to be in those environments will struggle.

Harald Steen, a co-author of the study, said that because there were empty nests and no dead chicks, researchers believe that the birds saw how difficult conditions were early in the breeding season and simply left their usual breeding grounds. According to the study, researchers observed fewer Antarctic seabirds in flight around research stations compared to previous years. This was another hint at how bad the snow storms were during the earlier part of the breeding season. Steen said this means that many of the birds flew back out to sea instead of sticking around.

“They’re very adapted,” Steen told Earther. “They can cope, but if the frequency of these breeding failures increase, then we will expect that the colonies will diminish in the long run.”