Space exploration takes tons of planning, technological expertise, and daring. And given the long timescales involved, they often require considerable patience. Many upcoming missions to deep space aren’t happening any time soon, but that doesn’t mean we can’t be excited.

Our investigations of the final frontier have only just begun. Our immediate neighbourhood — the solar system — has barely been touched by our species, with many places still grossly under-explored. Thankfully, a number of missions planned for the coming years and decades will help us to fill some of these gaps.

All of the missions described in this article have been approved and are either already underway or currently in development. So barring something unforeseen, they are going to happen. For clarification, we deliberately chose to exclude missions to the Moon, not because they’re uninteresting or unimportant, but because they’re amazing in their own right and deserve a dedicated article.

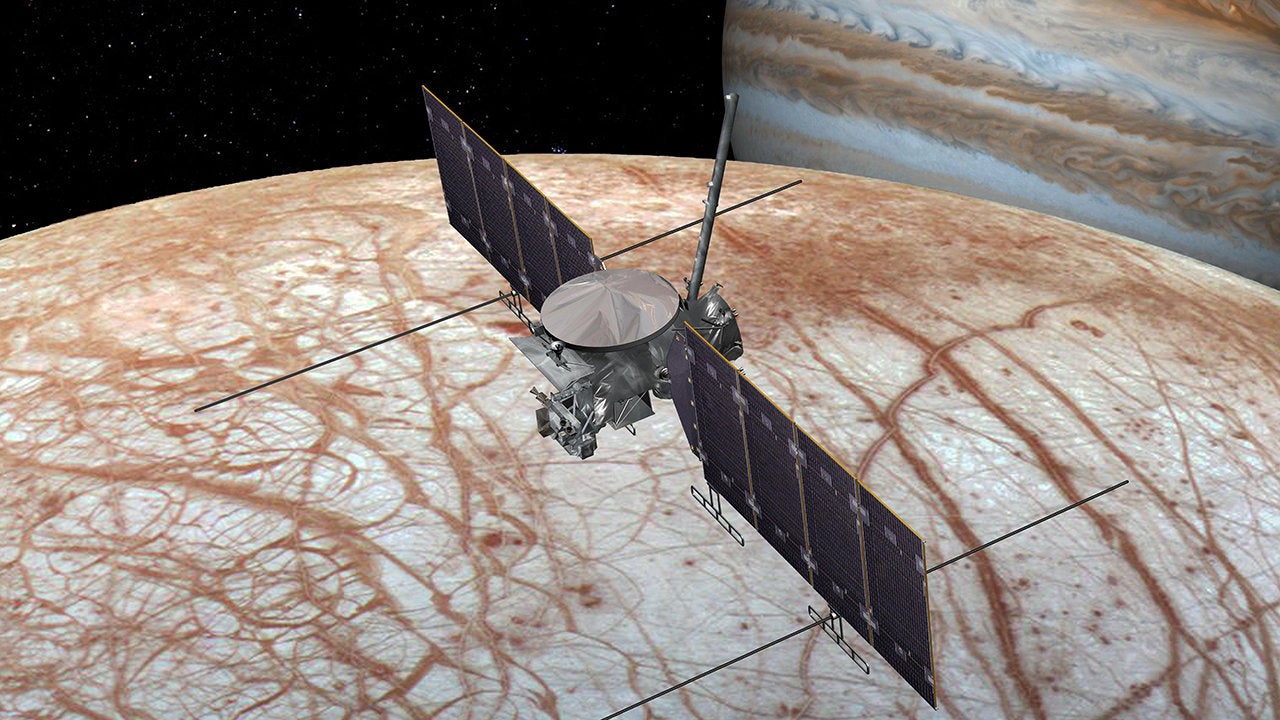

JUICE, the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer

The European Space Agency’s JUpiter ICy moons Explorer, or JUICE spacecraft, is set to launch on April 13, 2023, atop an Ariane 5 rocket. The probe will head to Jupiter, but its primary targets are three icy moons: Ganymede, Callisto, and Europa. These moons are of great interest to both planetary scientists and astrobiologists, as they feature dynamic surfaces and possibly warm liquid oceans tucked beneath their icy surfaces.

JUICE is expected to arrive at Jupiter in 2031 following an eight-year journey. The spacecraft will make history in 2034 by becoming the first probe to fully orbit a moon other than our own. At 4,808 kg, JUICE is unusually heavy, but its 10 onboard instruments will undoubtedly collect a dazzling array of data, including the chemical compositions of each moon and their complex surface topography, among many other measurements. Indeed, JUICE is poised to redefine our understanding of the Galilean moons.

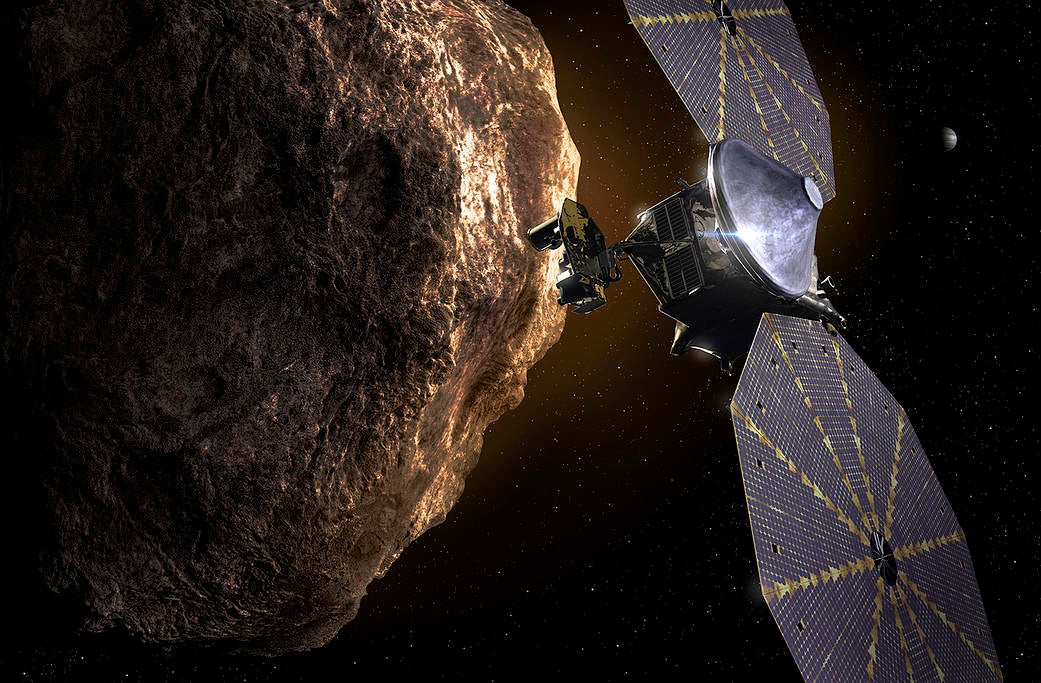

Psyche, a mission to a metallic world

Set for launch on October 10, 2023, NASA’s Psyche will be the first spacecraft to explore a metallic asteroid. The asteroid, also called Psyche, measures 140 miles (226 kilometers) across and is located in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. Scientists suspect the asteroid of being the leftover core of a planetesimal, that is, the initial building block of a solar system planet. In addition to testing a new communications system, the Psyche probe will use its high-resolution cameras to visualise the asteroid, use radio waves to measure the object’s gravity, and employ a spectrometer to identify its basic elements. Psyche will reach its target in 2026, where it will orbit for 21 months. The probe was supposed to launch in 2022, but mission development problems resulted in the delay.

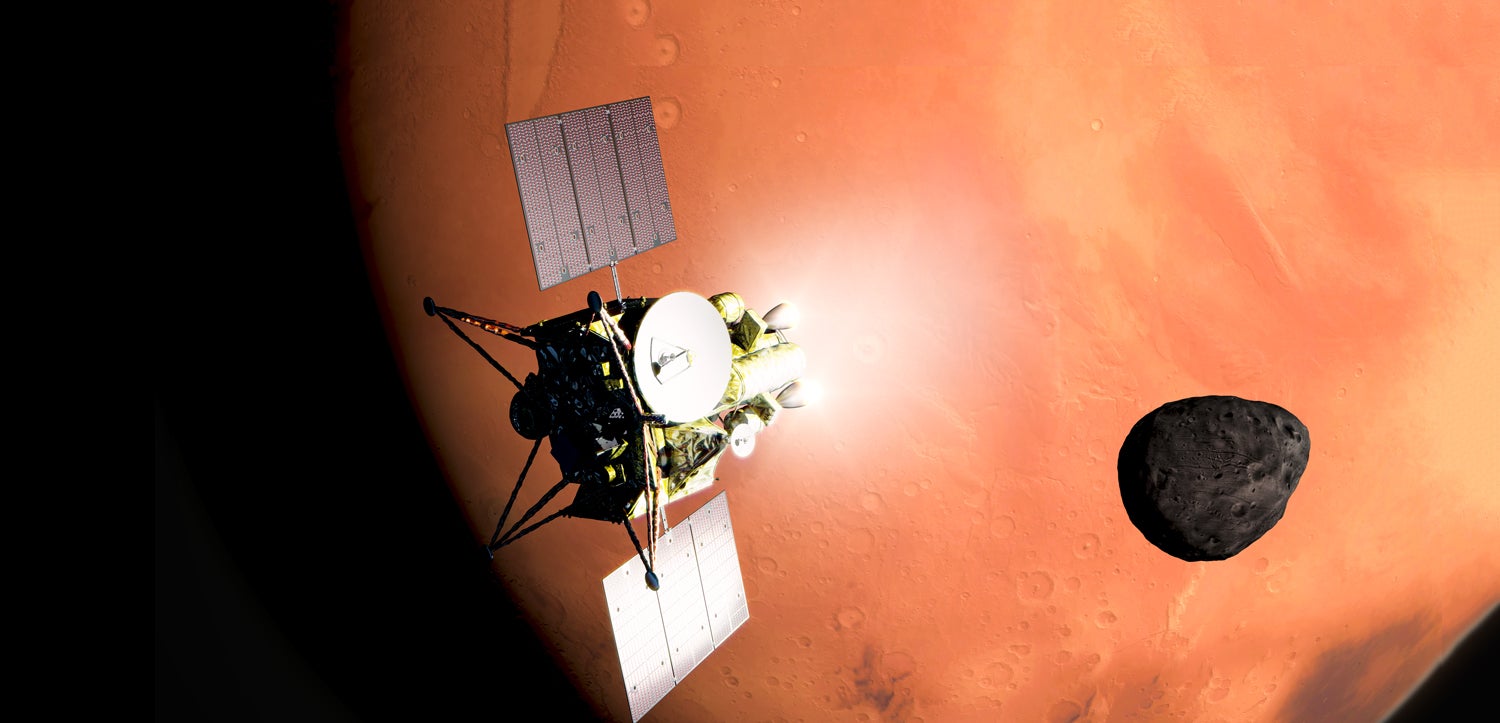

Japan’s Martian Moon eXploration (MMX)

The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) has a neat mission planned for later this decade called Martian Moon eXploration, or MMX. The probe will visit the two Martian moons, Phobos and Deimos, to test new technologies and investigate these enigmatic celestial bodies. Excitingly, the probe will attempt to collect surface samples from Phobos and then return to Earth in 2029 with its precious cargo. JAXA says MMX will “help improve technology for future planet and satellite exploration,” such as tech needed for round-trips to Mars. There’s also some important science involved, as MMX will seek to clarify the origin of the two Martian moons.

Lucy mission to Jupiter’s Trojan asteroids

NASA’s Lucy probe launched in October 2021, and despite an annoying problem with its power-supplying solar array, which didn’t deploy fully after launch, the spacecraft is working properly. Lucy is currently en route to Jupiter’s Trojan asteroids — two discernable clumps of asteroids that travel ahead and behind Jupiter along its orbital path around the Sun.

More on this story: 7 Things to Know About NASA’s First Mission to the Jupiter Trojan Asteroids

Jupiter’s Trojans have been trapped in this configuration for billions of years, making them tantalising targets for scientific investigation. As potential precursors to planetary formation, the Trojans could shed new light on the ways in which organic materials and water were delivered to Earth. The plan is for Lucy to investigate two main belt asteroids prior to reaching the Trojans. The probe will begin its tour of the Trojans in 2027, starting with Eurybates and its binary partner Queta, followed by Polymele, Leucus, Orus, Patroclus, and Menoetius. Lucy will investigate both Trojan clusters, which are located 500 million miles (800 million kilometers) from the Sun.

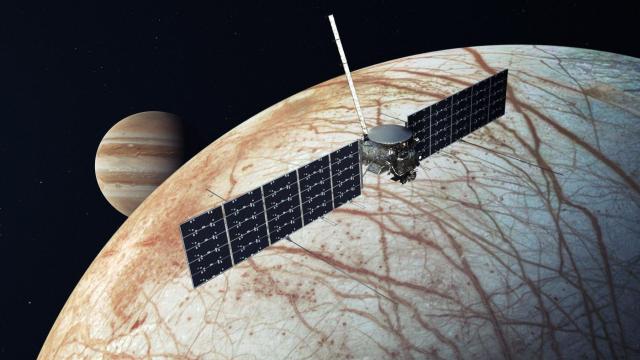

NASA’s Europa Clipper

NASA’s Europa Clipper is slated to launch in 2024 and reach its target in 2030. Once in orbit around Jupiter, the probe will perform nearly 50 close flybys of its moon Europa, coming as close as 16 miles (25 km) to its icy surface. A primary goal of the mission is to spot potentially habitable locations beneath Europa’s icy shell. To that end, the probe will analyse Europa using an array of instruments, including cameras, spectrometers, and ice-penetrating radar. With Europa Clipper, we’ll finally be able to peer inside this fascinating frozen world.

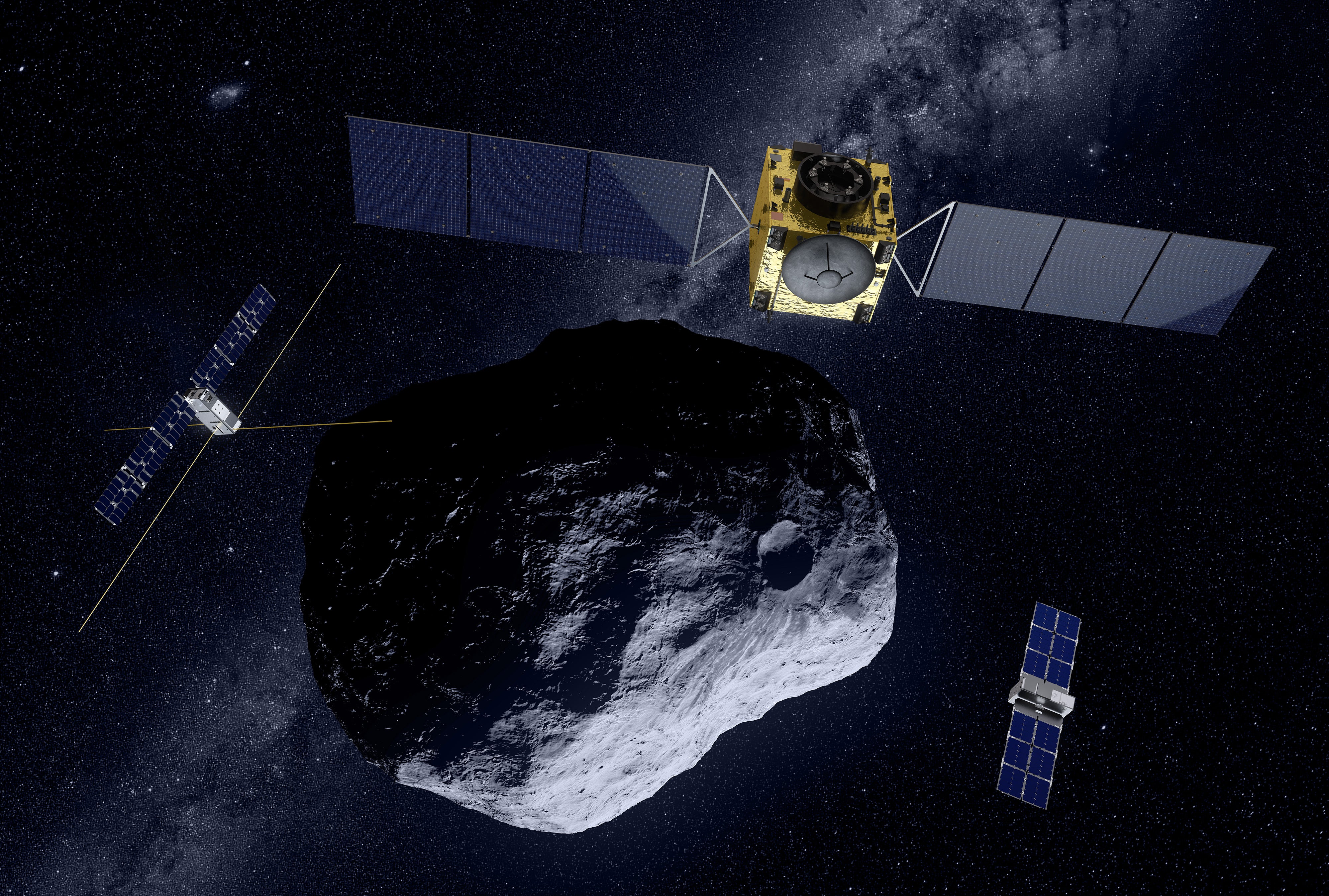

Hera mission to re-visit Dimorphos

Hera is the sequel mission to NASA’s wonderfully successful DART mission to deflect a harmless asteroid. To recap, DART — short for Double Asteroid Redirection Test — smashed into the tiny Dimorphos asteroid in September 2021, altering its orbital trajectory around its larger companion, Didymos, by a whopping 32 minutes (the team would’ve been happy with a 73-second change). The purpose of this exercise was to test a potential planetary defence strategy against legitimately threatening asteroids.

Related story: NASA’s DART Is No More, but This Future Probe Is Hoping to Take a Second Look

Scientists are still in the process of evaluating DART and its full effect on Dimorphos, but the upcoming Hera mission, in which the European Space Agency (ESA) probe will revisit the system in December 2026, will provide added colour. Hera will evaluate potential changes to Dimorphos’s orbital trajectory and surface composition, including signs of a potential crater. The probe will bring along two companions, CubeSats named Milani and Juventas, which will perform spectral analyses of the lingering dust cloud created by the impact.

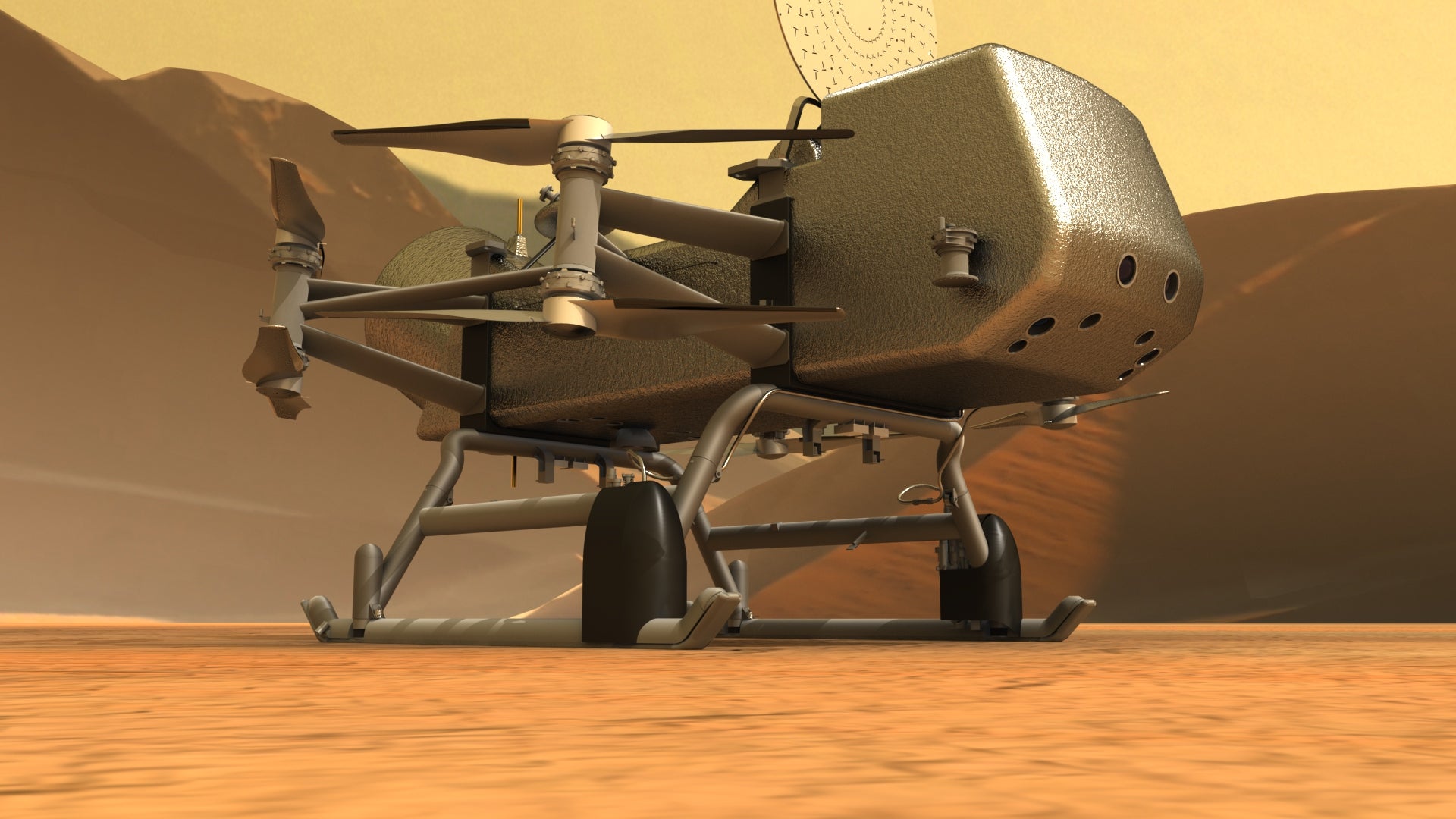

A Dragonfly on Saturn moon’s Titan

As NASA’s Ingenuity helicopter has successfully demonstrated on Mars, it’s possible for us to fly aircraft on other worlds. The next important phase in this capability is Dragonfly — a rotorcraft that’s set to arrive on Saturn’s moon Titan in 2034. Over the duration of its planned 2.7-year mission, NASA’s Dragonfly will explore Titan’s sand dunes, study the moon’s complex weather and atmosphere, and hunt for signs of prebiotic chemical processes. Dragonfly is expected to launch in 2027.

The dual-quadrotor drone will have no difficulties flying through Titan’s thick atmosphere, but it will have to endure temperatures as low as -300 degrees Fahrenheit. Should all go well, Dragonfly will perform around 25 flights and fly a total distance of roughly 110 miles (180 kilometers). Personally, I can’t wait for high-resolution images of Titan’s methane lakes.

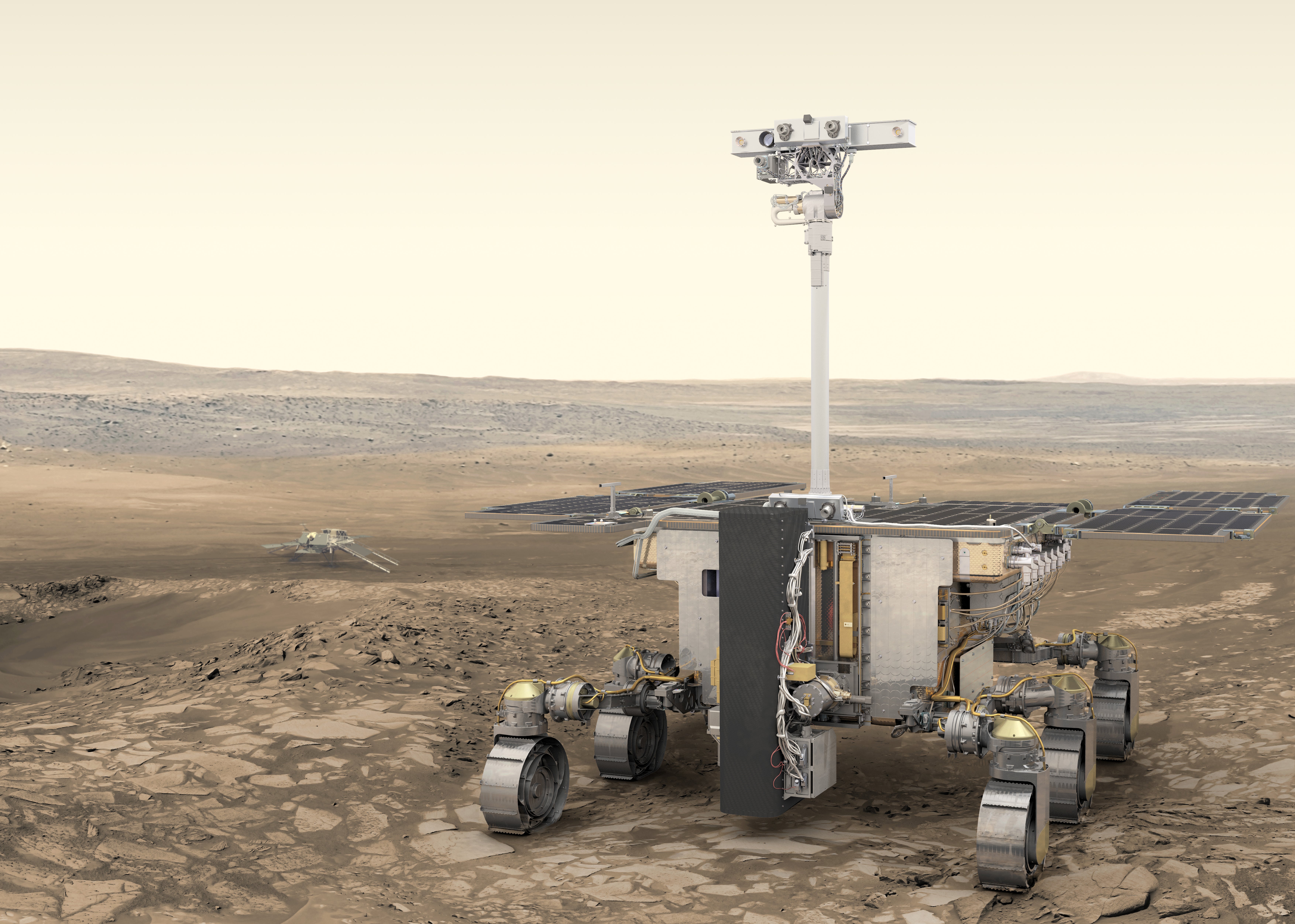

The Rosalind Franklin Mars rover

Originally known as the ExoMars rover, the European Space Agency’s Rosalind Franklin rover is a delayed mission to the Red Planet. The six-wheeled rover was originally scheduled to launch in 2018, and then again in 2020, but developmental delays held the mission back. The rover was set to go for a launch in 2022, but Russia’s invasion of Ukraine compelled ESA to sever its ties with the Russian space agency Roscosmos. The mission is on permanent hiatus as ESA and its partners work to develop a lander for the mission, a replacement for the Russian Kazachok lander.

Once Europe’s rover finally gets to Mars, however, this will be an exciting mission. The rover has the capacity to collect surface samples at depths reaching 6 feet (2 meters) and then study the materials using its onboard lab kit. Rosalind Franklin, named for the famed British chemist, will also search for signs of prior habitability on Mars. The rover will be capable of handling challenging terrain and is expected to cover as much as 328 feet (100 meters) per Martian day.

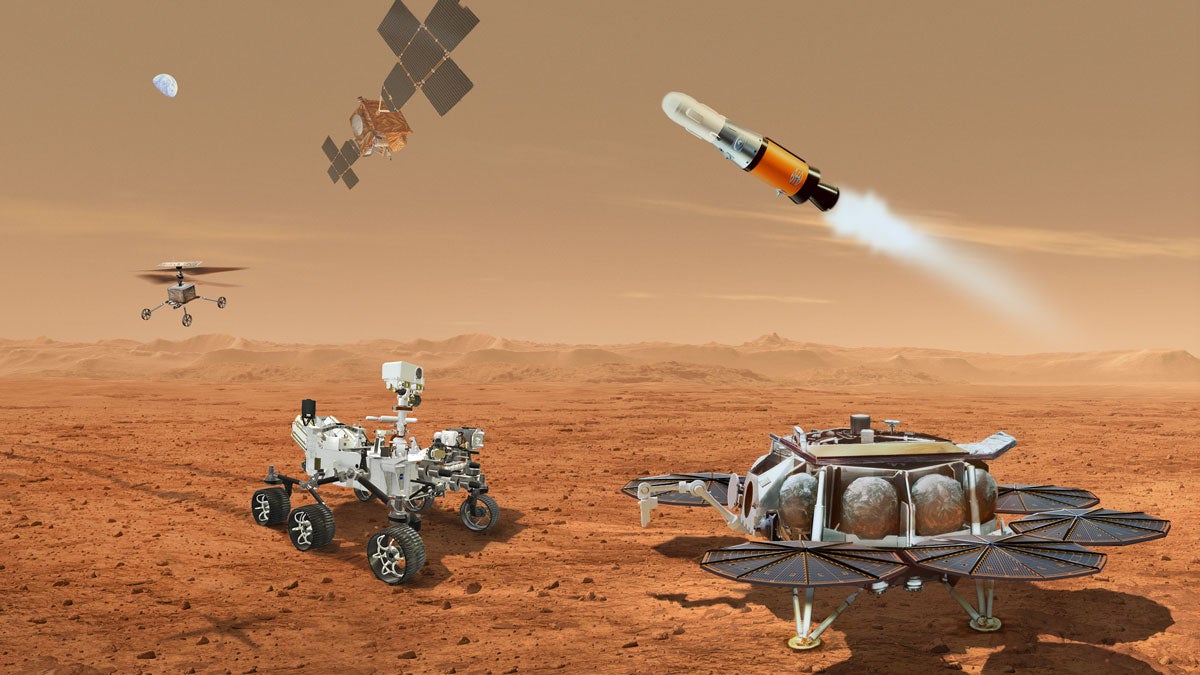

The Mars Sample Return mission

Of all the missions listed here, perhaps none are as technologically and logistically complex as the Mars Sample Return Mission, a joint project between NASA and ESA. The mission is already in full swing, with NASA’s Perseverance rover having dropped 10 sample tubes filled with rock samples onto the Martian surface for later retrieval. Getting these samples back to Earth will require a future Martian orbiter, two Ingenuity-class helicopters (with wheels!), further cooperation from Perseverance, a sample retrieval lander, and an ascent vehicle.

More on this story: NASA Is Sending More Helicopters to Mars, and This Time They’ll Have Wheels

The plan is for the helicopters to retrieve some sample tubes, and for Perseverance to pack the tubes into the sample retrieval lander. Once loaded, the sample carousel will get placed inside the ascent vehicle. The rocket will rendezvous with the orbiter, which will in turn send the samples on a journey back to Earth, arriving here sometime around 2033. As I said, this will take some doing to pull off.

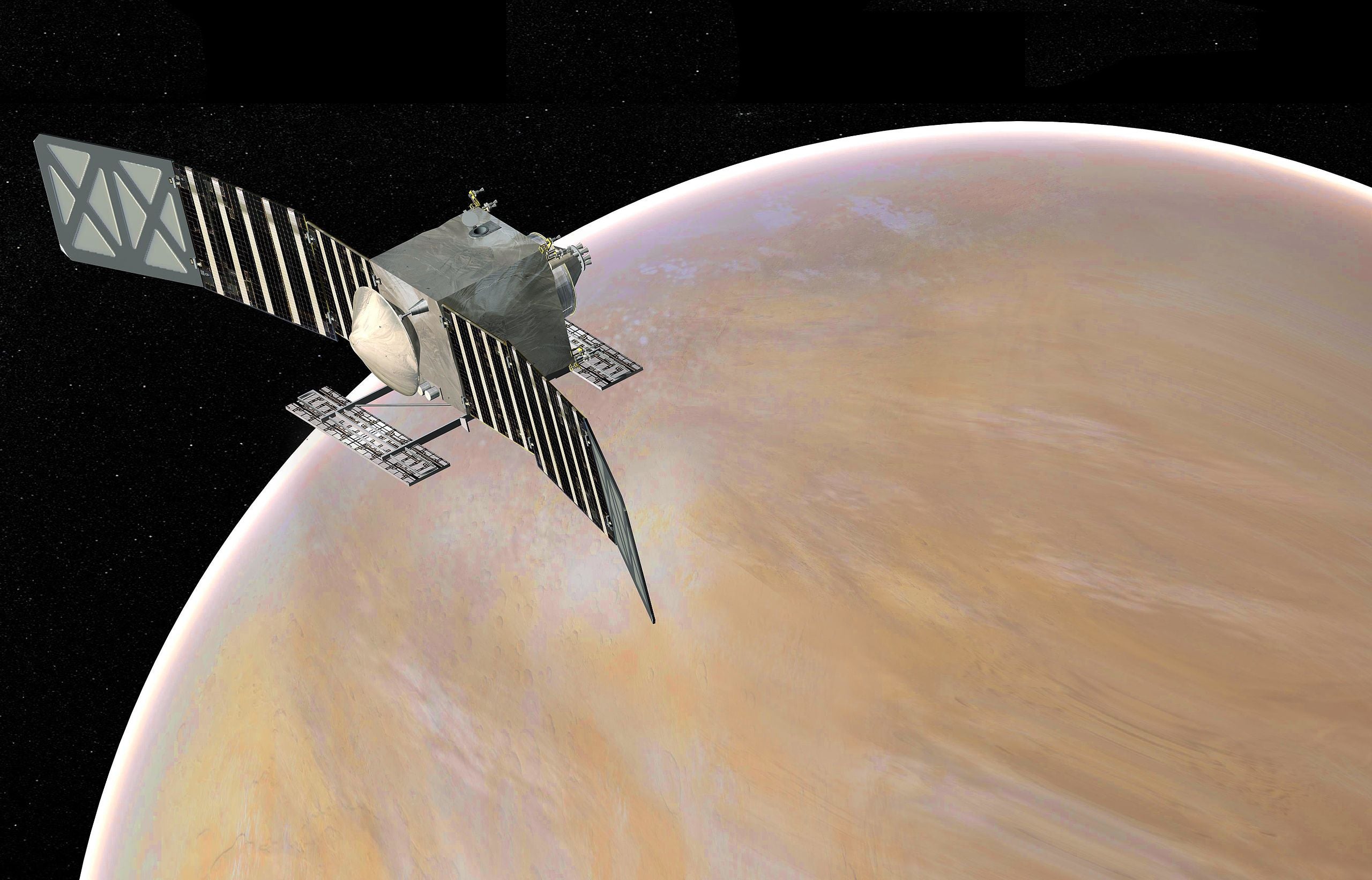

Three missions to Venus

There are no less than three missions to Venus in the works: VERITAS, DAVINCI, and EnVision. We’ve neglected Venus as a scientific target, but these missions should correct this oversight.

There’s no launch date for NASA’s VERITAS, but this probe will study our evil twin from orbit to figure out why it became so inhospitable to life despite it being so similar to Earth in terms of size and composition.

Unlike VERITAS, NASA’s 0.91 m-wide (1 metre) DAVINCI probe will take the plunge and perform a one-hour-long descent through Venus’s thick atmosphere, which it will do in 2031. Once DAVINCI starts its descent, “a parachute, being designed to survive Venus’s harsh environment, will deploy to slow it down,” NASA explains. “After the probe travels halfway to the surface, the parachute will be jettisoned; at this point, Venus’s atmosphere becomes so thick, 90 times thicker than Earth’s, that the probe will slow down naturally, settling like a stone in water.” DAVINCI isn’t expected to survive for very long on the surface, where temperatures can reach 900 degrees Fahrenheit.

Like VERITAS, ESA’s EnVision probe will settle in orbit around Venus, where it will remain for the duration of its 4-year mission. A key goal of the project, done in partnership with NASA, is to study interactions between the surface and atmosphere, which display high levels of interactivity.