Versatile and prolific author Adrian Tchaikovsky won the Arthur C. Clarke Award in 2016 for his sci-fi tale Children of Time, but he’s equally as well known for his Shadows of the Apt fantasy series. He returns to the fantasy genre with his next novel, City of Last Chances, and Gizmodo has a first look today!

Here’s a description of the story:

There has always been a darkness to Ilmar, but never more so than now. The city chafes under the heavy hand of the Palleseen occupation, the choke-hold of its criminal underworld, the boot of its factory owners, the weight of its wretched poor and the burden of its ancient curse.

What will be the spark that lights the conflagration?

Despite the city’s refugees, wanderers, murderers, madmen, fanatics and thieves, the catalyst, as always, will be the Anchorwood – that dark grove of trees, that primeval remnant, that portal, when the moon is full, to strange and distant shores.

Ilmar, some say, is the worst place in the world and the gateway to a thousand worse places.

Ilmar, City of Long Shadows.

City of Bad Decisions.

City of Last Chances.

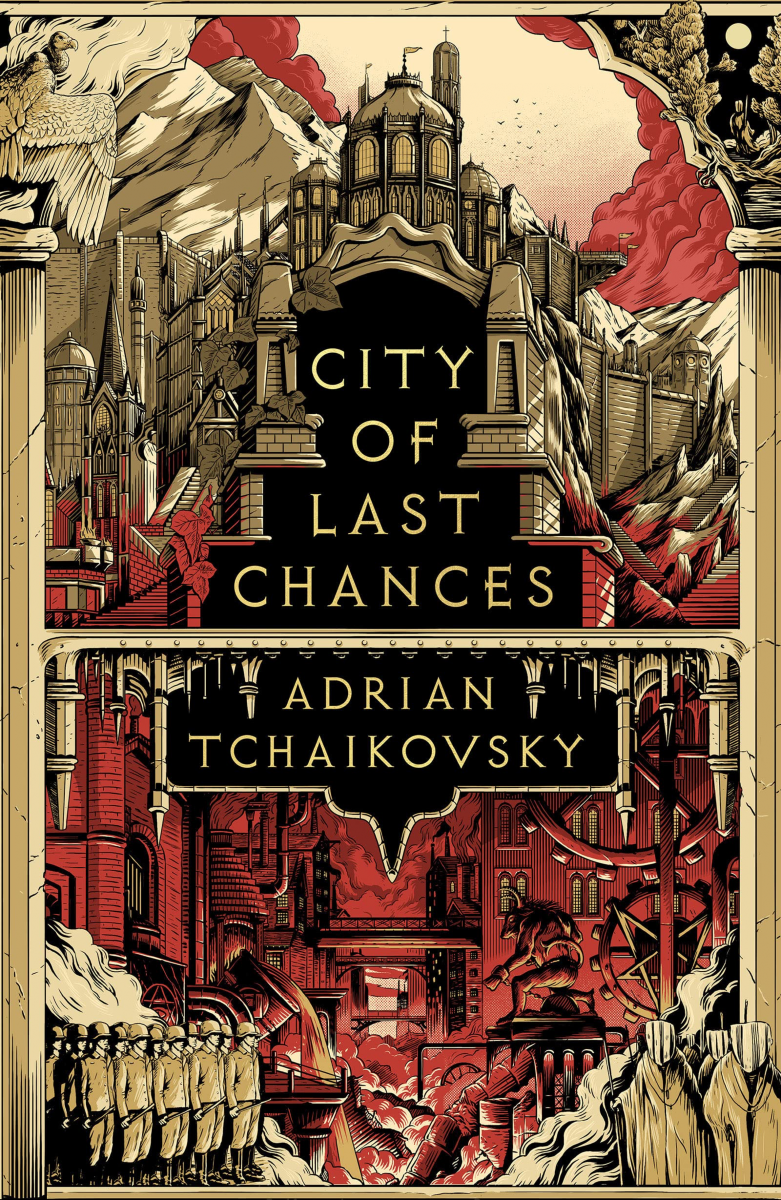

Here’s the full cover, followed by the excerpt.

Yasnic the priest. Thin and not young, though not quite old. Half lost in clothes tailored for a larger man in the voluminous Ilmari style. Face hollow, hair greying before it should, thinning, creeping back from his temples like an army that, seeing its opposition is time, no longer has the will to fight…

That morning, God was complaining again. Yasnic lay crunched up in bed, knees almost to his chin and his feet twined together. Trying to tell from the way the light filtered in through the filthy window whether the frost was just on the outside, or on the inside again. He could have put a hand out to touch the panes and check. He could have put a foot out and kicked out at God. Or the far wall. It was, he decided, a blessing. A small room held his body heat longer. If he’d been able to afford anything larger, then he’d have needed a hearth and to buy wood or coal, or even magical tablethi, to heat the place.

“It’s cold,” God said. “It’s so cold.” The divine presence was curled up on His shelf like an emaciated cat, and about the same size. He had shrunk since the night before, and perhaps that, too, was a blessing. Sometimes Yasnic could do with a little less God in his life, and here he was this morning, and God was smaller by at least a quarter. He gave thanks, his knee-jerk reaction ingrained from long years of good upbringing from Kosha, the previous priest of God. Back when Ilmar had been a more tolerant place, and old Kosha and Yasnic and God had lived in three rooms above a tanner’s and had meat at least once a twelveday.

Not a twelveday, he reminded himself. The School of Correct Exchange was levying fines and making arrests for people using the old calendar, he’d heard. He had to start thinking in terms of a seven-day week, except then he couldn’t look back on the way things had been and quantify the time properly. How often had they had meat, back when he’d been a boy learning at Kosha’s knee? What was seven into twelve or twelve into seven or however it might work? His mathematics weren’t good enough to work it out. And so, obscurely, it felt as though a swathe of his memories was locked away by the new ordnances. Also, he’d just given thanks to God that he had less God in his life, and God, the recipient of those thanks, was right there and staring at him accusingly.

“I need a blanket,” said God. “It’s only the beginning of winter, and it’s so cold.”

God looked all skin and bones. He wore rags. It was only a season since Yasnic had sacrificed a good shirt to God, but the diminished state of the faith – meaning Yasnic – tended to mean anything God got His hands on didn’t last. A blanket would go the same way.

“I only have one blanket,” Yasnic told God.

“Get another one.” God stared at His sole priest from His place on the shelf up by the low ceiling. His spidery hands were gripping the edge, His nose and wisps of beard projecting over them. His skin was wrinkled and greyish, hollowed until the shape of His bones could be seen quite clearly. “In the old days I had robes of fur and velvet, and my acolytes burned sandalwood — ”

“Yes, yes, I know.” Yasnic cut God off. “I only have this blanket.” He lifted the threadbare covering and regretted it instantly, the chill of the morning taking up residence in a bed with room only for one. “I suppose I’m getting up now,” he added pettily.

“Please,” said God. Yasnic stopped halfway through forcing numb feet into his overtrousers. God looked in a bad way, he had to admit. It was easy just to think that God was being selfish. God had, after all, been very used to people doing what He said and giving Him all good things, back in the day. Back in a day long before Yasnic, last priest of God, had come along. Their religion had been dying for over a century, ever since the big Mahanic Temple had been raised. And yes, Mahanism had actively spoken against other religions, but more, they’d just… expanded to fill all the available faith. People went where the social capital was. And now, under the Occupation, there really were people purging religions. Making arrests for Incorrect Speech. Just as well it’s only me and God, Yasnic thought. Easier to go unnoticed.

“Ask the woman,” God said. “Ask her for another blanket. I’m cold.”

“Mother Ellaime will not give us another blanket,” Yasnic said. In fact, their landlady would more likely want to ask about last twelved — last week’s rent. And that was another thing, of course. Since the Occupation, everything had to be paid sooner, because of the weeks. And he couldn’t quite make the maths work, but it seemed he was paying more each day of the seven than he had each day of the twelve. And it wasn’t as though being the sole surviving holy man of God actually brought in much. There were few perks and no regular take-home wage. And, under the Occupation, begging meant risking arrest for Incorrect Exchange.

“I’ll see what I can do.” Clothes on, he shambled out of the room and went down for tea. One thing Mother Ellaime did provide her boarders with was a constantly churning samovar by the fire, and both fire and tea were just about enough to set up Yasnic for a day’s scrounging.

God hadn’t been with him on the stairs but was sitting beside the samovar down in the common room. Yasnic took down a cup from its hook and filled it with dark green, steaming liquid. He wanted to avoid Mother Ellaime’s notice as he jostled elbows with his fellow boarders to get space at the single table. God was there, though. God was hunched cross-legged on the tin plate Yasnic’s neighbour had eaten porridge off.

“Ask her,” God insisted.

“I won’t do it,” murmured Yasnic. His neighbour, the big man named Ruslav who never seemed to have a job but always seemed to have money, stared at him. He couldn’t see God sitting in the remains of his porridge. He probably thought Yasnic wanted to lick his plate clean. Jealously, he pulled it closer to himself, making God scrabble for balance. Yasnic winced, aware that everyone was looking at him now, even the student girl who’d turned up a tw — two weeks ago, and whom he dreaded talking to. She was very clever, and Gownhall people loved to argue metaphysics. He was afraid he’d listen to her tortuous logic too much and then look around for God, only to find God wasn’t there anymore. And he was afraid of what he might feel, if that were ever the case.

“Ask,” God insisted peevishly. “I command it.”

“Mother,” Yasnic said. “I don’t suppose I could beg another blanket from you?” Loud enough to carry to the old woman. Aware that his quiet words were expanding to fill the room. Feeling the student’s judging eyes on him. Feeling ashamed. And it wasn’t even a useful shame, the sort that earned you credit with God or, in this case, got you a blanket, because Mother Ellaime was already shaking her head. And if there was a little more money, there might be another blanket. And likely that would mean someone at the table, who had a little less money, would be missing a blanket, because it was a closed blanket economy here at Mother Ellaime’s boarding house. And if it had just been Yasnic, he would have accepted the lack of a blanket and known that he was making someone else’s life better, and tried to warm himself with that. But it was God, and God was old and petty and selfish, but God was also cold, and Yasnic had given himself into God’s service. And so he begged Mother Ellaime, with the whole table listening archly to every word. With Ruslav, who probably had two blankets or even three, snickering in his ear. God was cold, and God didn’t have anyone else. And it was all for nothing because there wasn’t another blanket to be had, not without money he didn’t possess.

Excerpt from Adrian Tchaikovsky’s City of Last Chances reprinted by permission of Head of Zeus.

Adrian Tchaikovsky’s City of Last Chances releases May 2; you can pre-order a copy here.

Want more Gizmodo news? Check out when to expect the latest Marvel, Star Wars, and Star Trek releases, what’s next for the DC Universe on film and TV, and everything you need to know about James Cameron’s Avatar: The Way of Water.

Editor’s Note: Release dates within this article are based in the U.S., but will be updated with local Australian dates as soon as we know more.