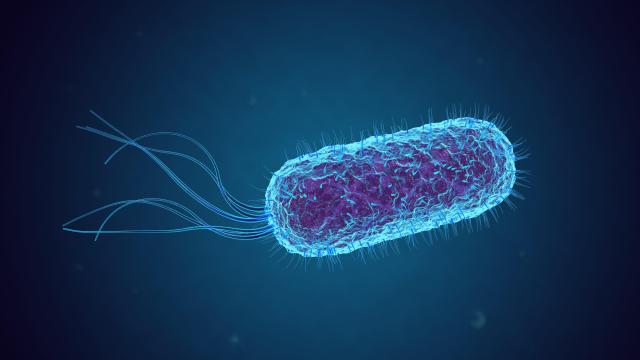

Scientists in China are hoping to turn Escherichia coli bacteria into a cancer-fighting ally. In a new study, they describe their creation of genetically engineered E. coli strains that can kill different types of tumours in mice. More studies will be needed, but the authors believe that bacterial therapy for cancer can become a reality.

The idea of cancer-fighting bacteria has been around for decades. Some bacteria are known to naturally infect or kill cancer cells very well. Their small size and other attributes could also make them an effective delivery method for a multitude of treatments. At the same time, there have been major roadblocks in the development of bacterial cancer therapy, particularly in making it safe enough to use in humans. But researchers at the Shenzhen University School of Medicine and elsewhere say they might have figured out how to solve some of these problems.

Their new study, published Monday in Cell Reports Medicine, describes the development of two E. coli strains genetically engineered to fight cancer. One strain, called mp105, is designed to target a variety of different cancer types and can be delivered intravenously. It’s also intended to survive for only a very short time, hours at most, which should limit its potential to harm noncancerous cells. The second strain, called m6001, is designed to live longer and seek out solid tumours by sensing and moving away from glucose (these tumours tend to be deprived of glucose).

Ideally, this means that it could be delivered directly to the tumour site without safety issues.

In both lab and mice experiments, mp105 and m6001 appeared to work as expected. Mp105 was found to have direct and indirect effects on the mice’s cancers. It outright killed cancer cells, but it also depleted tumour-associated macrophages — a group of immune cells found in tumours that are thought to aid their survival — and it seemed to boost the body’s natural immune response to the cancer. M6001 had even more potent anticancer activity against the solid tumours it was deployed against. But the best results were seen when mp105 and m6001 were used together. No major short-term health risks were found when using either strain as well.

Of course, this is just a single study involving mice. Much more research has to be done to validate the results seen here and to test out long-term safety before human trials would enter the picture. There might also still be ways to improve the effectiveness of the team’s bacteria. But if their research continues to show promise, the team believes that their two-pronged approach would be able to cover a variety of cancers. Mp105 could treat many different cancers systematically, for instance, while m6001 could help control solid tumours locally, including in combination with mp105.

“The two anticancer bacteria and their combination are applicable to different scenarios, turning bacterial therapy for cancer into a feasible solution,” the study authors wrote.

This is only the latest research to explore using microbes to fight cancer. Scientists are already conducting clinical trials of viruses engineered to target cancers, for instance.