It’s the 50th anniversary of the launch of NASA’s Skylab — the space station that laid the groundwork for the International Space Station. These days, the orbital lab is mostly remembered for the hysteria it created prior to crashing down to Earth, but it’s important to reflect on its historical legacy.

Skylab was the first U.S. space station, launching to low Earth orbit on May 14, 1973. The orbiting lab had only three crews during its short life, but each successive mission set new duration records, in addition to providing unprecedented scientific and technical data. As NASA reflected 10 years ago, Skylab proved that “humans can live and work in outer space for extended periods of time.”

A simple start

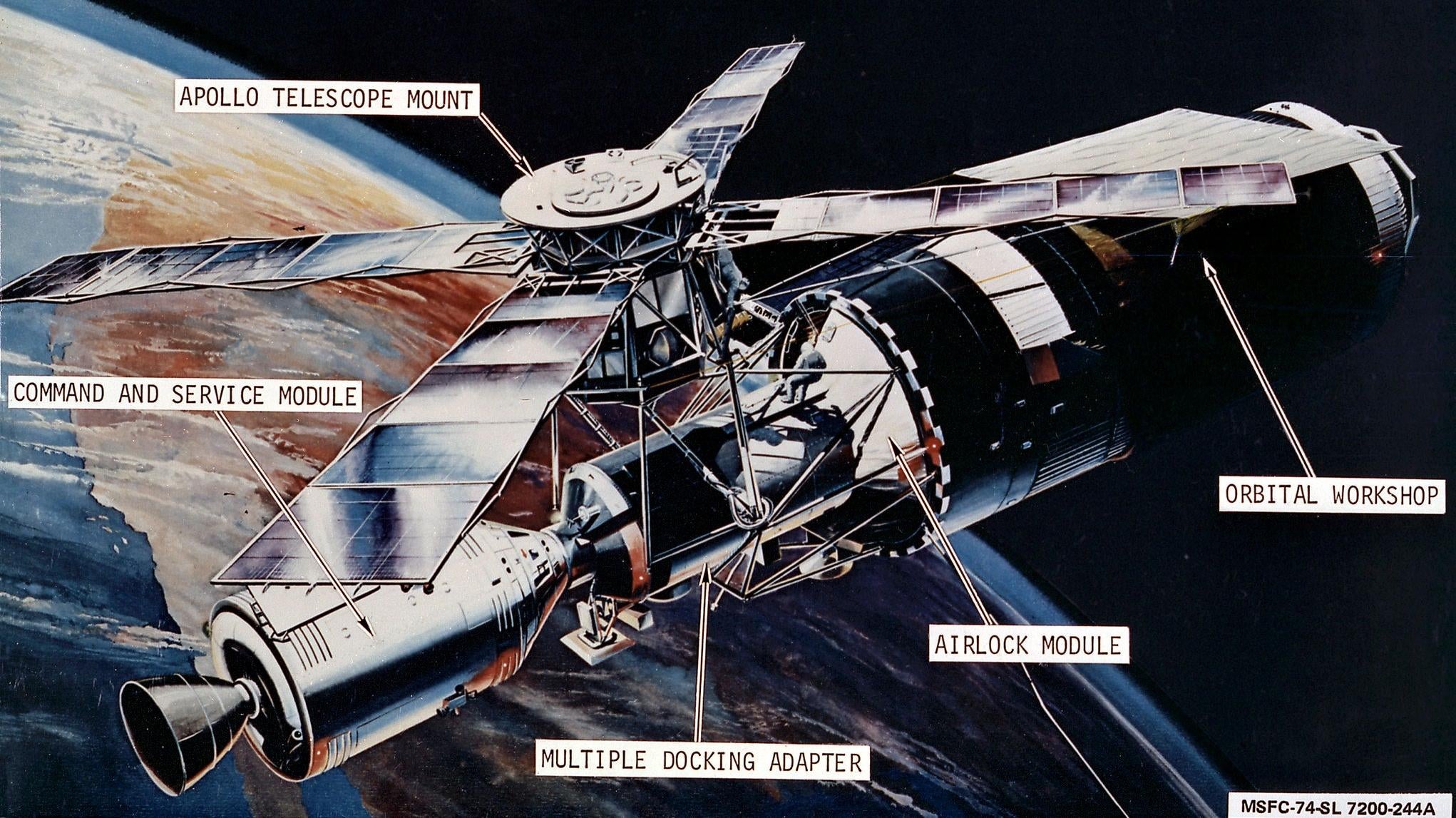

Parked in low Earth orbit and travelling around our planet at 25,750 km per hour, Skylab allowed for detailed observations of the Earth and Sun, acted as a medical lab, enabled novel microgravity experiments, and served as the first platform for studying the effects of long-duration spaceflight. It consisted of several main elements: the command and service module, multiple docking adaptor, airlock module, Apollo telescope mount, and orbital workshop, the latter being a converted Saturn rocket upper stage. A key goal of the Skylab project was to use as much hardware from the Apollo missions as possible.

“The program demanded innovation and ingenuity,” Rocco Petrone, director of NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Centre from 1973 to 1974, wrote in a 1977 NASA report. “Experience and knowledge gained from earlier space programs provided a solid foundation on which to build, but the Skylab Program was truly making new pathways in the sky.”

Embarking on a new era in space exploration

Skylab launched to space from NASA’s Kennedy Space Centre on May 14, 1973, aboard a Saturn V rocket — the same type of rocket that launched Apollo astronauts to the Moon. The launch was not without incident, however, as vibrations caused the station’s micrometeorite and thermal shield to fall off 63 seconds into the launch.

“Debris from the torn shield jammed one of the arrays, preventing it from opening, and a plume from a retrorocket used to separate the Saturn V’s second stage from Skylab impinged on the second array, in its slightly open configuration, tearing it completely off the station,” wrote NASA’s John Uri in a 2020 retrospective.

Once in orbit, this resulted in serious power issues at the station that required immediate attention from the first crew, which launched to Skylab later that same month. The missing thermal shield also meant that the station’s workshop was unprotected from the Sun’s damaging rays.

Fabricating a replacement heat shade

With the shield gone, NASA had to scramble to create a replacement heat shade for the Skylab Orbital Workshop, as temperatures inside Skylab were untenable, reaching 52 degrees C. NASA engineers devised a solution and trained the first crew on how to implement the fixes. The image above shows a team putting the heat shade together at the GE building across the street from Johnson Space Centre in Houston, Texas. The parasol solar shield, made from layers of aluminised mylar, laminated nylon ripstop, and thin nylon, was designed to protect the workshop from the Sun’s hot rays.

Launch of the first Skylab crew

The first crewed mission to the space station was called Skylab 2, as the mission to launch the space station to orbit was called Skylab 1 (this naturally resulted in confusion, with original mission patches mistakenly referring to crewed missions one through three). A modified and trimmed-down Saturn V rocket, called the Saturn IB, launched the first crew to Skylab on May 25, 1973 (the crew was supposed to go up the day after Skylab reached orbit, but the problematic launch forced a delay).

The inaugural crew consisted of commander Pete Conrad, pilot Paul Weitz, and scientist Joe Kerwin, the latter being the first medical doctor to fly in space. The photo above shows the Saturn IB perched atop the “milkstool” pedestal, as NASA called it.

Oops, there it isn’t

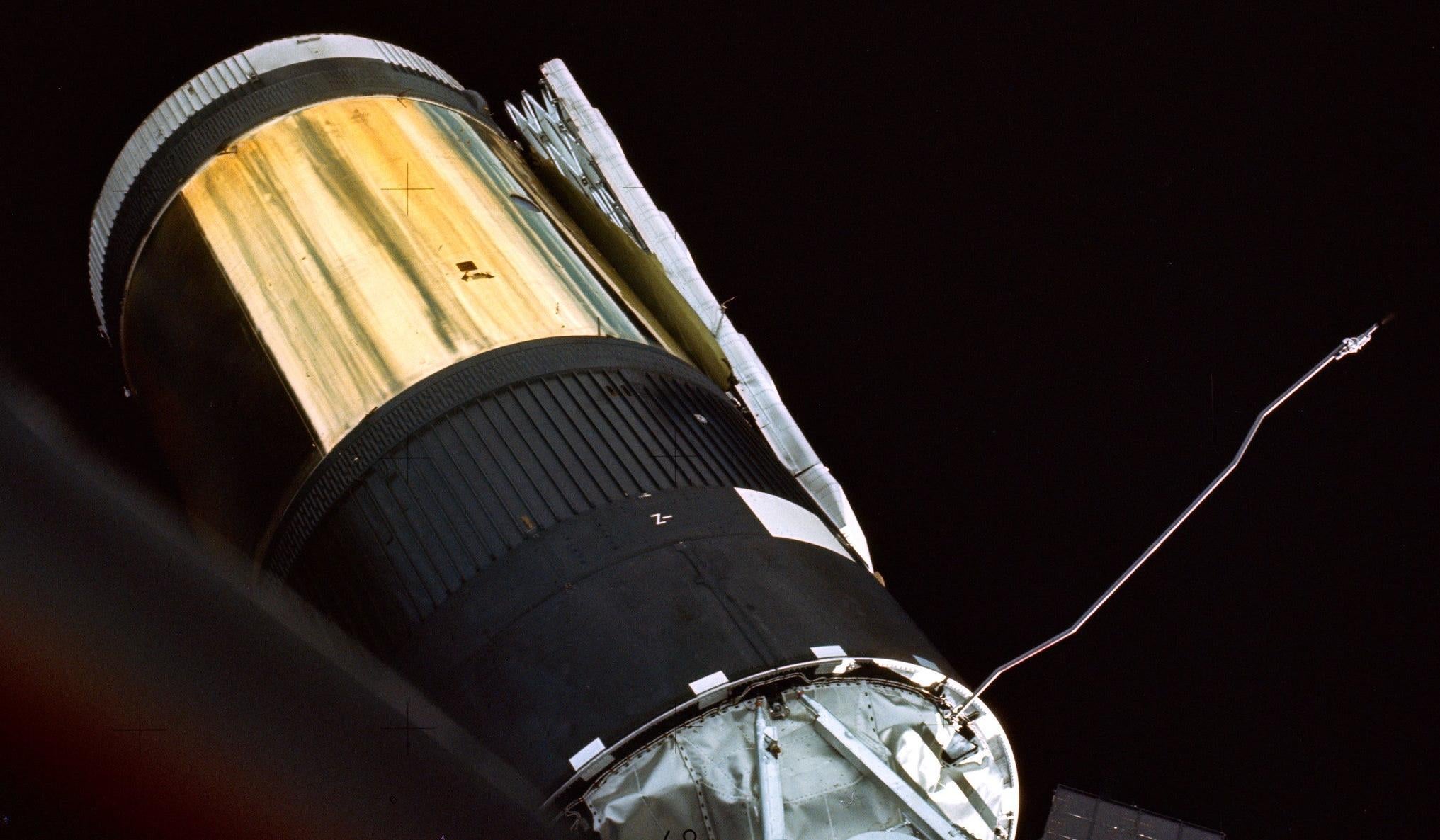

The inaugural Skylab crew captured this image of the outpost on arrival, showing the missing micrometeoroid shield and partially deployed solar array. “The Sun’s harsh rays had already begun to discolor and blister the exposed skin of the workshop,” and the newly arrived crew “could clearly see the thin strip of aluminium holding one array in a slightly open position and a tangle of severed cables where the second array had torn away,” Uri wrote.

The crew would later fit the makeshift parasol solar shade in place of the mission shield and fix the solar array during a series of spacewalks. Prior to the fix, the station had to be powered by four smaller ATM arrays, which weren’t enough to power Skylab’s systems and experiments.

Orbital repairs

The image above shows Kerwin on June 7, 1973, during one of the spacewalks done to repair the damaged station. He’s using a cutting tool to remove metal that jammed the solar array and caused it to get stuck in a partially opened position. The efforts of Kerwin and Conrad “allowed the solar panels to fully deploy and provide the needed electricity for the three Skylab expeditions,” according to NASA. The parasol sunshade also worked, cooling interior cabin temperatures down to 23.8 degrees C.

Little station, big goals

NASA had multiple objectives with Skylab, which included advancing our understanding of the Earth, Sun, stars, and cosmic space, investigating the impact of weightlessness on living organisms, including humans, exploring the effects of processing and manufacturing materials in zero gravity, and conducting observations of Earth’s resources. Instruments used to observe our home planet were collectively known as the Earth Resources Experiment Package. Additionally, Skylab performed 19 experiments designed by high school students. The image above clearly shows the makeshift heat shade covering the Orbital Workshop.

Putting theory to practice

We currently take it for granted that astronauts can live and work in microgravity environments for extended periods of time, but this was terra incognita — or more accurately astra incognita — at the time. For context, the Soviet Union’s doomed Soyuz 11 mission to the world’s first space station, Salyut 1, lasted for 23 days, but all three cosmonauts died during atmospheric reentry. “I think the greatest achievement is that we pretty much proved that the human body can stay weightless for a very long time,” said Jerry Carr, commander of NASA’s Skylab 4 mission. “This was our first opportunity to go up and settle in.”

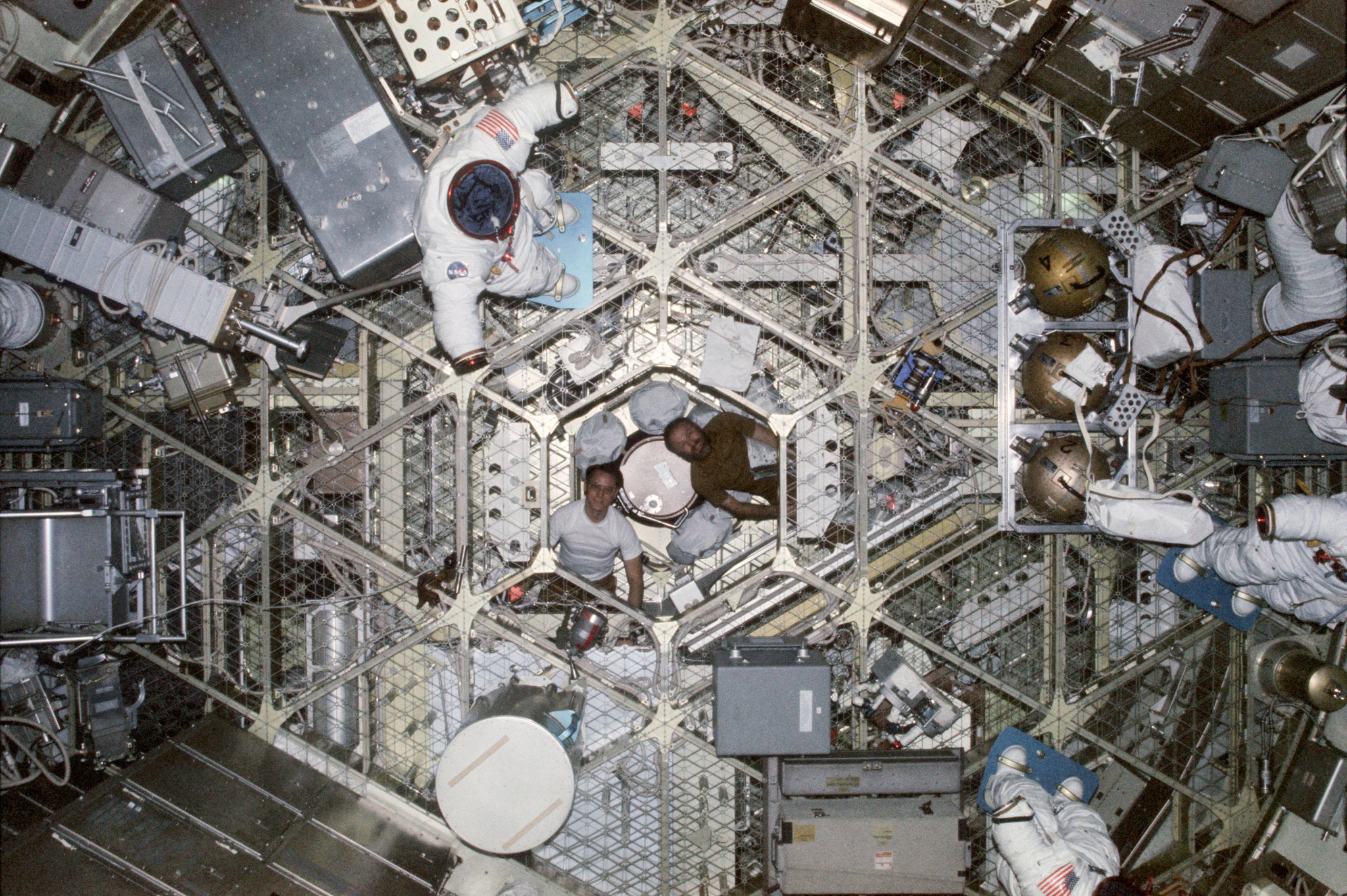

The image above shows Carr (at right), along with Skylab 4 scientist Edward Gibson. Their crew mate, pilot Bill Pogue, snapped the photo of the two men from the hatch leading into the airlock module, showing the length of the Skylab Orbital Workshop.

Orbital guinea pigs

For the Skylab crews, the work day began at 6:00 a.m. sharp and ended at 8:00 p.m., allowing for two hours of leisure time before bed. After breakfast, the crews would read the orders of the day, which mission control transmitted to an onboard teletype machine. The men spent their days performing experiments, doing routine maintenance tasks, and running medical experiments on each other. They improvised a lot, designing many experiments on the fly. “It was such an interesting thing to turn loose a blob of water to see what you can do with it,” Carr said afterward. In the image above, taken from a television transmission, Kerwin can be seen collecting a blood sample from Conrad.

Set the controls for the heart of the Sun

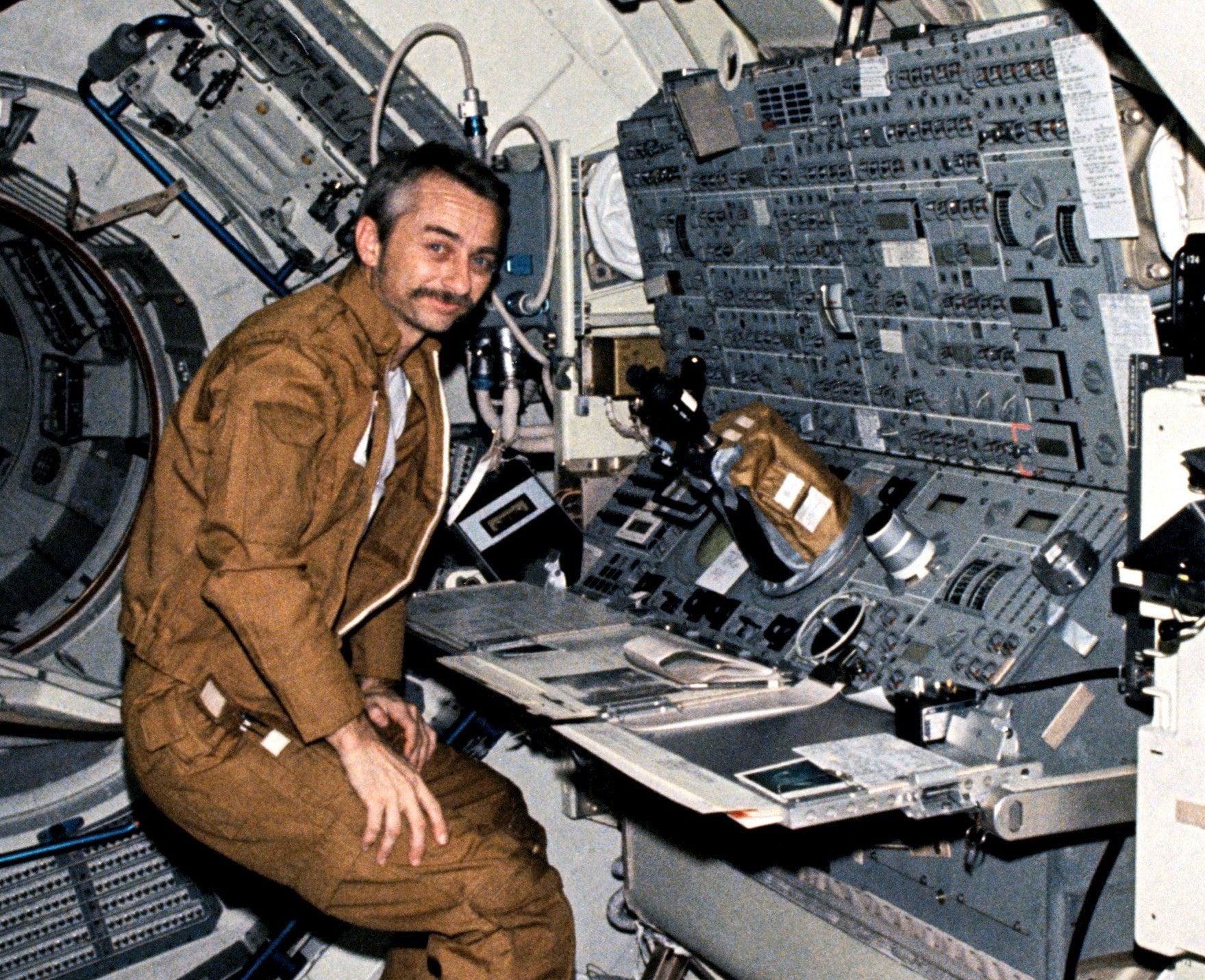

Skylab 3 launched on May 25, 1973, returning to Earth 59 days later. This crew consisted of commander Alan Bean, pilot Jack Lousma, and scientist Owen Garriott, pictured above operating the Apollo Telescope Mount. The crew was successful in deploying a second and more permanent sunshade to protect the station and keep it cool.

The Apollo Telescope Mount

Attached to Skylab, the Apollo Telescope Mount was a solar observatory that observed the Sun and other celestial phenomena in various wavelengths, including X-rays, ultraviolet, and visible light. A key achievement of the program were the observational studies done of our host star.

Record-breaking durations

Each of the three Skylab missions set new space duration records, with the Skylab 2 mission lasting for 28 days, Skylab 3 for 59 days, and the third and final mission, Skylab 4, lasting for 84 days — a record that stood for 20 years and was finally broken during the Shuttle-Mir program. Skylab 4 launched on November 15, 1973 and ended on February 8, 1974.

Planners initially overextended the Skylab 4 astronauts, leading to “frustrations as the astronauts struggled to keep up with the blistering pace of the timeline, allowing no time for familiarization or to recover from errors and hardware malfunctions,” according to Uri, adding that repeated requests by the crew to mission controllers to “lighten their schedule went unheeded for several weeks, leading to tension between the crew and the ground.” Skylab’s flight director later admitted that planners made mistakes during the opening stages of the Skylab 4 mission. Media claims made later that Carr, Gibson, and Pogue went on a one-day strike on December 27, 1973 were unfounded, according to Uri.

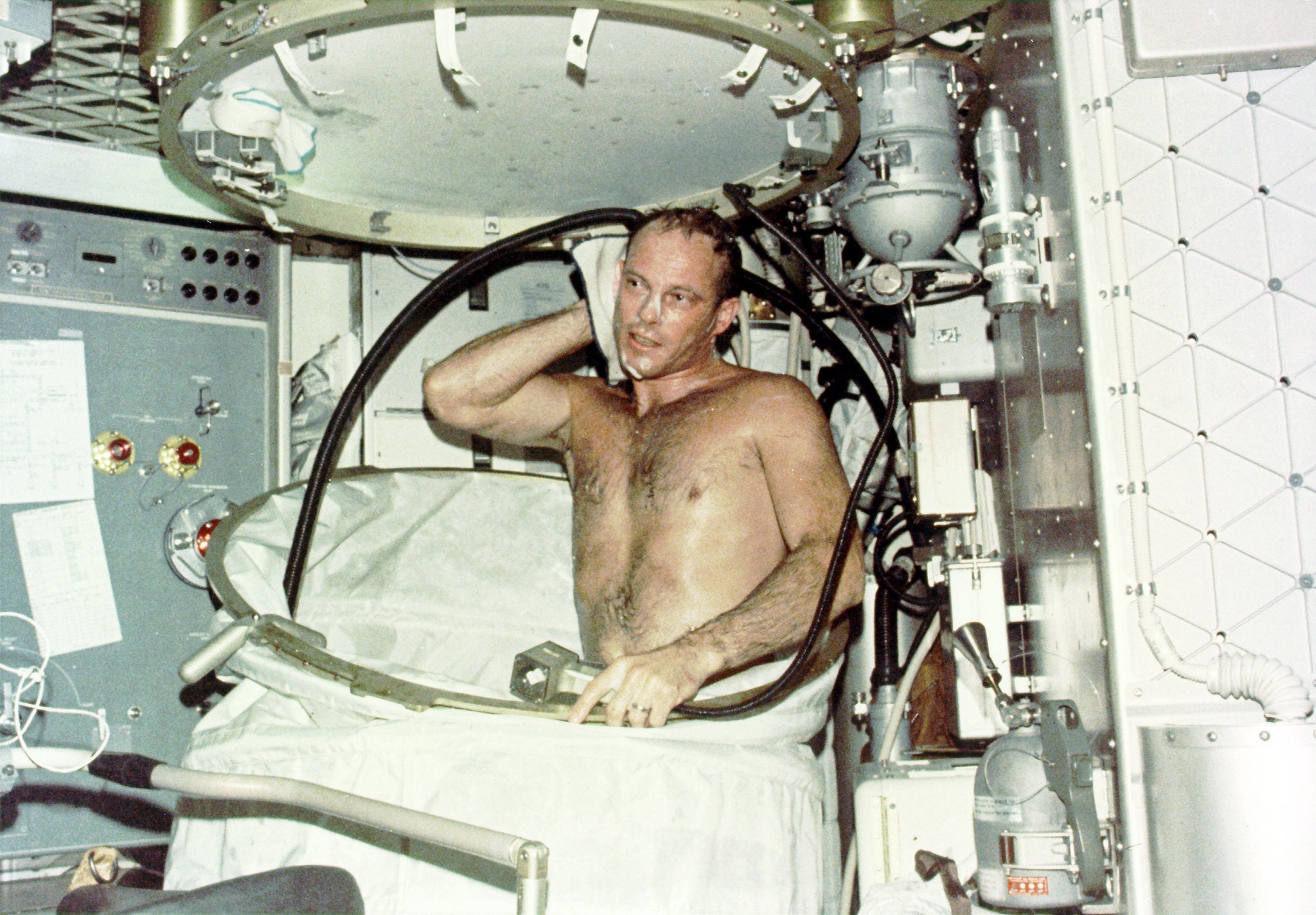

Keep it clean, boys

Skylab 3 astronaut Lousma can be seen here taking a hot bath in the crew quarters of the Orbital Workshop during the summer of 1973. “In deploying the shower facility the shower curtain is pulled up from the floor and attached to the ceiling,” according to NASA. “The water comes through a push-button shower head attached to a flexible hose. Water is drawn off by a vacuum system.”

Mmmm, space food

Skylab crews used this food-heating and serving tray, and though it looks clunky, it was a vast improvement over NASA’s previous attempts to feed its astronauts while in space; the system meant that astronauts no longer had to squeeze out their liquified food from plastic tubes. What’s more, the men were able to select their own food items and prepare them to their own tastes. The food shown outside of the tray consists of, starting from bottom left, grape beverage, beef pot roast, chicken and rice, beef sandwiches, and sugar cookie cubes. The tray itself consists of, from back left, orange beverage, strawberries, asparagus, prime rib, a dinner roll, and butterscotch pudding in the centre.

Plenty of EVAs

Skylab crews spent a lot of time outside the space station. Here, Skylab 3 astronaut Owen Garriott gazes at the camera while performing an extravehicular activity on August 6, 1973. Garriott, along with Lousma, worked to deploy the twin pole solar shield in the ongoing effort to shade the Orbital Workshop.

Science outside the station

After deploying the twin pole shield, the Skylab 3 spacewalkers deployed the Skylab Particle Collection S149 Experiment, which was mounted to the Apollo Telescope Mount. The purpose of this experiment was to “collect material from interplanetary dust particles on prepared surfaces suitable for studying their impact phenomena,” according to NASA. The Skylab 4 crew performed a pair of impromptu spacewalks to install an ultraviolet camera used to observe Comet Kohoutek.

A premature ending, but an incredible start

Skylab was supposed to last between eight and 10 years and even host the in-development Space Shuttle, but intense solar activity roused our atmosphere, forcing a premature end to the program and a fiery demise. Skylab returned to Earth on July 11, 1979, falling as debris over Western Australia and the southeastern Indian Ocean. The mission may have ended early, but it set the stage for bigger and better orbital things, including the ISS.